The past year has been another troubling one for the Russian free press.

Russian officials branded scores of independent news outlets “foreign agents” and “undesirable organizations” in retaliation for refusing to comply with the country’s wartime censorship laws.

As many as 17 media professionals have been detained in Russia for their work, bringing the total number of media workers imprisoned in the country to 28, according to data from Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

The case of U.S. journalist Evan Gershkovich has perhaps been most widely covered by international media.

Gershkovich, who was once a reporter at The Moscow Times, was accused of “espionage” after he was detained in Yekaterinburg while working on an assignment for The Wall Street Journal in May.

Russian officials claim that Gershkovich, an accredited Moscow-based reporter, tried to obtain classified defense information for the U.S. government. Moscow has so far provided no evidence to back up its allegations.

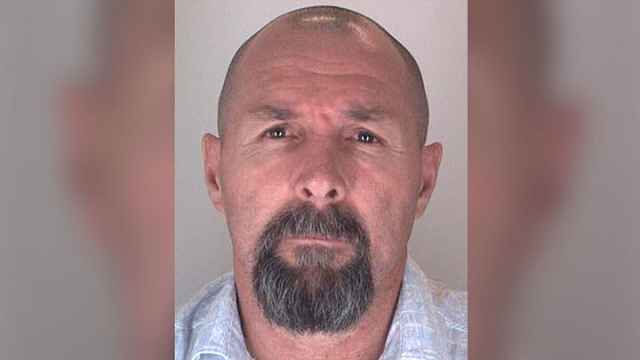

Many observers likened Gershkovich’s story to that of Nicholas Daniloff, a Moscow bureau chief for U.S. News & World Report who was arrested by Soviet authorities in 1986. He spent 13 days in detention before being returned to the U.S. in a prisoner swap.

Unlike his predecessor’s swift release, Gershkovich has already spent nearly eight months in Moscow’s notorious Lefortovo Prison, where Soviet political prisoners were once tortured and executed.

“This is a much harsher regime than that which existed when I was arrested,” Daniloff told The Moscow Times shortly after Gershkovich’s arrest. “The Russians are being difficult.”

Another American citizen who will be greeting 2024 in a Russian detention facility is Alsu Kurmasheva, a journalist for the Tatar-Bashkir service of the U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL). She was arrested while visiting family in her native republic of Tatarstan in October.

A court in Kazan already found Kurmasheva — who also holds Russian citizenship — guilty of failing to notify the authorities of her American citizenship and ordered her to pay a 10,000 ruble ($110) fine.

Kurmasheva still faces additional accusations of violating Russia’s “army fakes” and “foreign agent” laws, crimes that are punishable by up to 15 and five years in prison respectively.

Though Kurmasheva has not been individually designated a foreign agent, RFE/RL and its regional affiliates were granted the label years ago. In a first, Russian officials claimed that a journalist employed by a “foreign agent” must proactively request for her name to be added to the register.

Imposing strict financial reporting and self-disclosure requirements, the “foreign agent” label has been disproportionately used by Russian officials to target independent media and individual journalists who comprise more than 40% of the register, according to Vyorstka.

Some of this year’s additions to the foreign agent list include independent news outlets The Moscow Times, Tayga.Info, Bumaga, Sota, 7x7, Groza and investigative news outlet Proekt, as well as dozens of prominent journalists, including Artemy Troitsky, Andrei Loshak and Bulgarian investigative reporter Christo Grozev.

Far more consequential than the “foreign agent” label is being added to the list of “undesirable” organizations, which requires an entity to cease all operations in Russia. It also allows any funds and assets in the country to be confiscated.

In 2023, the independent news outlets Meduza and Novaya Gazeta Europe as well as broadcaster TV Rain were all declared “undesirable.”

With their staff relocated abroad, all three outlets were able to continue operating in defiance of the risks the designation exposes its staff and donors to. Readers could also face prison time for sharing these outlets’ materials.

But not all media outlets have the capacity to stand up to the regime.

Russia’s draconian wartime censorship laws have been a death sentence for many independent publishers operating in Russia’s regions where funding has always been scarce.

Dozens of regional journalists have already been imprisoned for violating laws introduced in the wake of the war or shedding light on local crime and corruption in their reporting.

In February, Siberian journalist and activist Maria Ponomarenko was sentenced to six years in prison for publishing information about the Russian bombing of a theater in the occupied Ukrainian port city of Mariupol.

In September, journalist Mikhail Afanasyev from the Siberian republic of Khakassia was sentenced to more than five years in prison for reporting on the refusal of 11 local riot police officers to be deployed to Ukraine.

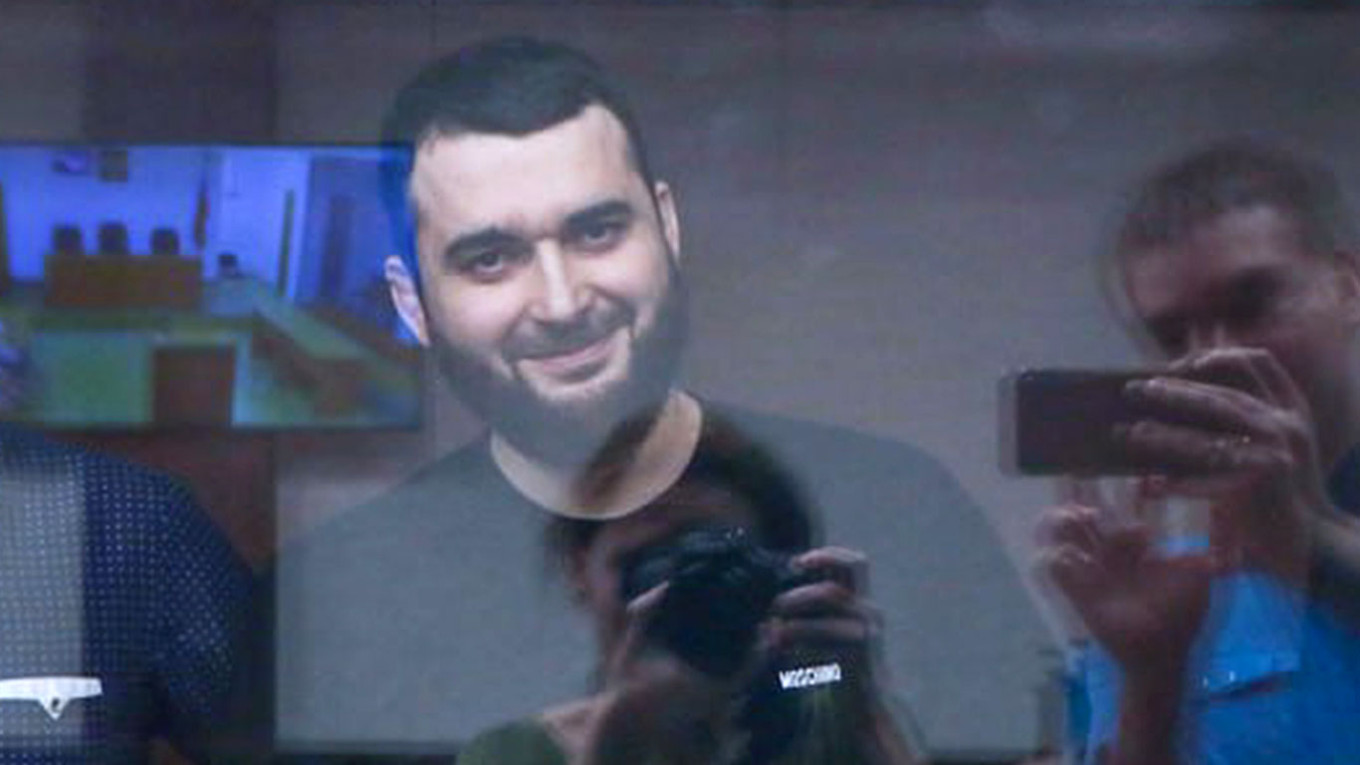

The same month, a court in the southern city of Rostov-on-Don sentenced independent journalist Abdulmumin Gadzhiev to 17.5 years in prison on charges of participating in and financing a terrorist organization.

In his final word in court, Gadzhiev called the case against him “fake from start to finish.” Both his colleagues and independent observers believed it to be a retaliation for his professional activities.

In addition to imprisonment, journalists reporting on Russian regions continue to face the threat of extrajudicial violence.

In July, journalist Yelena Milashina, who covers rights abuses in Chechnya for the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, was held at gunpoint and badly beaten during a work trip to the republic’s capital Grozny.

Milashina — who was attacked similarly on a visit to Chechnya in 2020 — vowed to continue her work in the region despite the attack.

“I will continue to travel to Chechnya, whether [Chechen leader Ramzan] Kadyrov wants me to or not,” Milashina vowed in the wake of the attack. “I need to go back to the scene of the crime.”

Many regional news outlets and their editorial teams chose to continue their work despite the very real risks they face, hoping that their reporting would support what remains of Russia’s civil society and prevent people from falling prey to the Kremlin’s propaganda.

“It is important to have a conversation now about local interests, how much tax we are paying, what we need, and what our neighbors need,” Viktor Muchnik, a veteran journalist and editor-in-chief of exiled regional media project Govorit NeMoskva, told The Moscow Times in January.

“If anything is needed in the [Russian] media world today it is, in my opinion, local journalism,” he added.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.