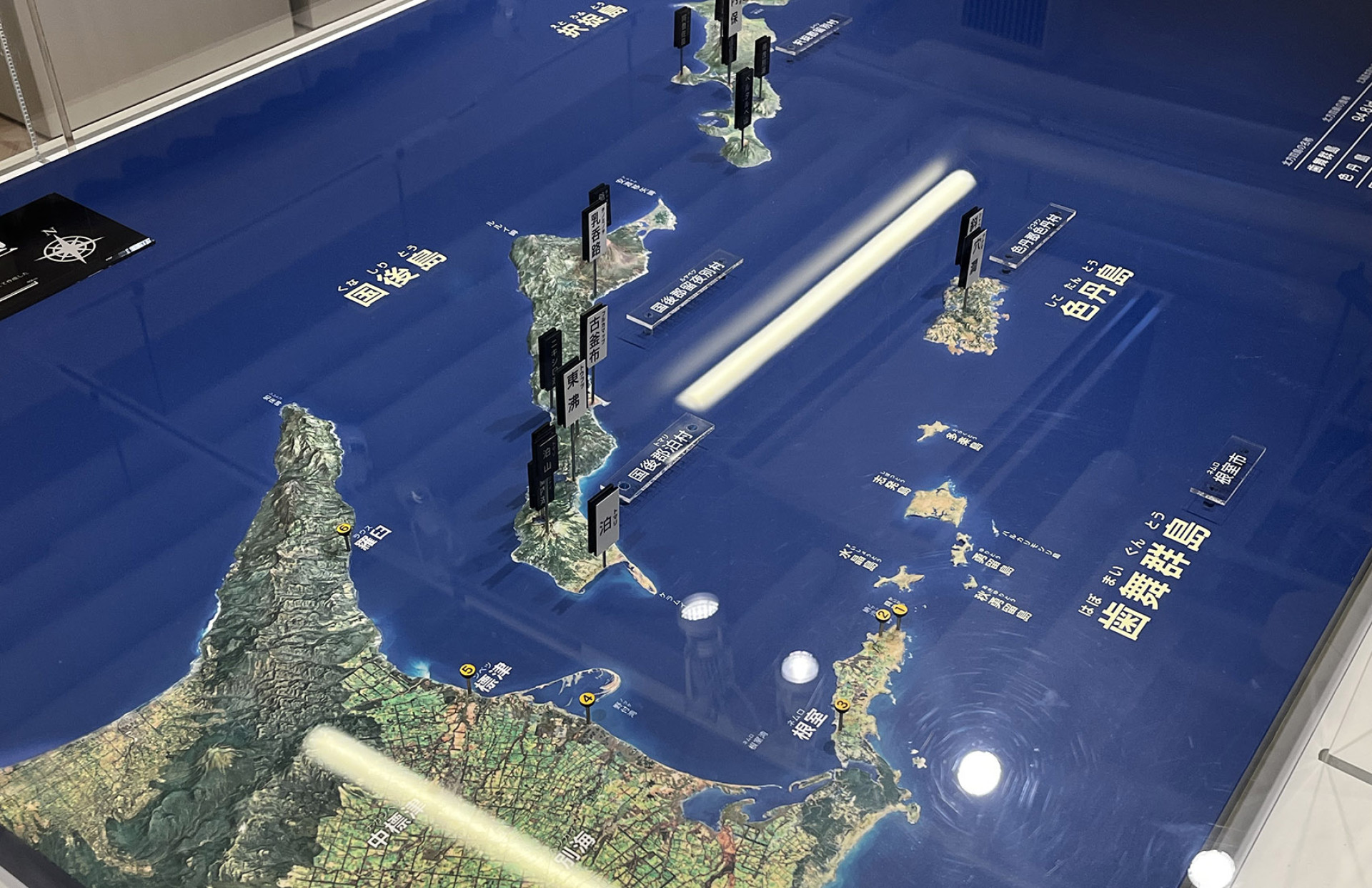

SAPPORO, Japan — Tucked away in the basement of this northern Japanese city’s local history museum is a small exhibit devoted to one of World War II’s most enduring territorial disputes.

Known as the “Northern Territories Exhibition Room,” it is less a neutral display than a quiet appeal, inviting visitors not only to learn about history, but to also help undo it.

In one corner, a table is filled with forms where visitors are encouraged to write letters pledging their “support for the return of the Northern Territories.”

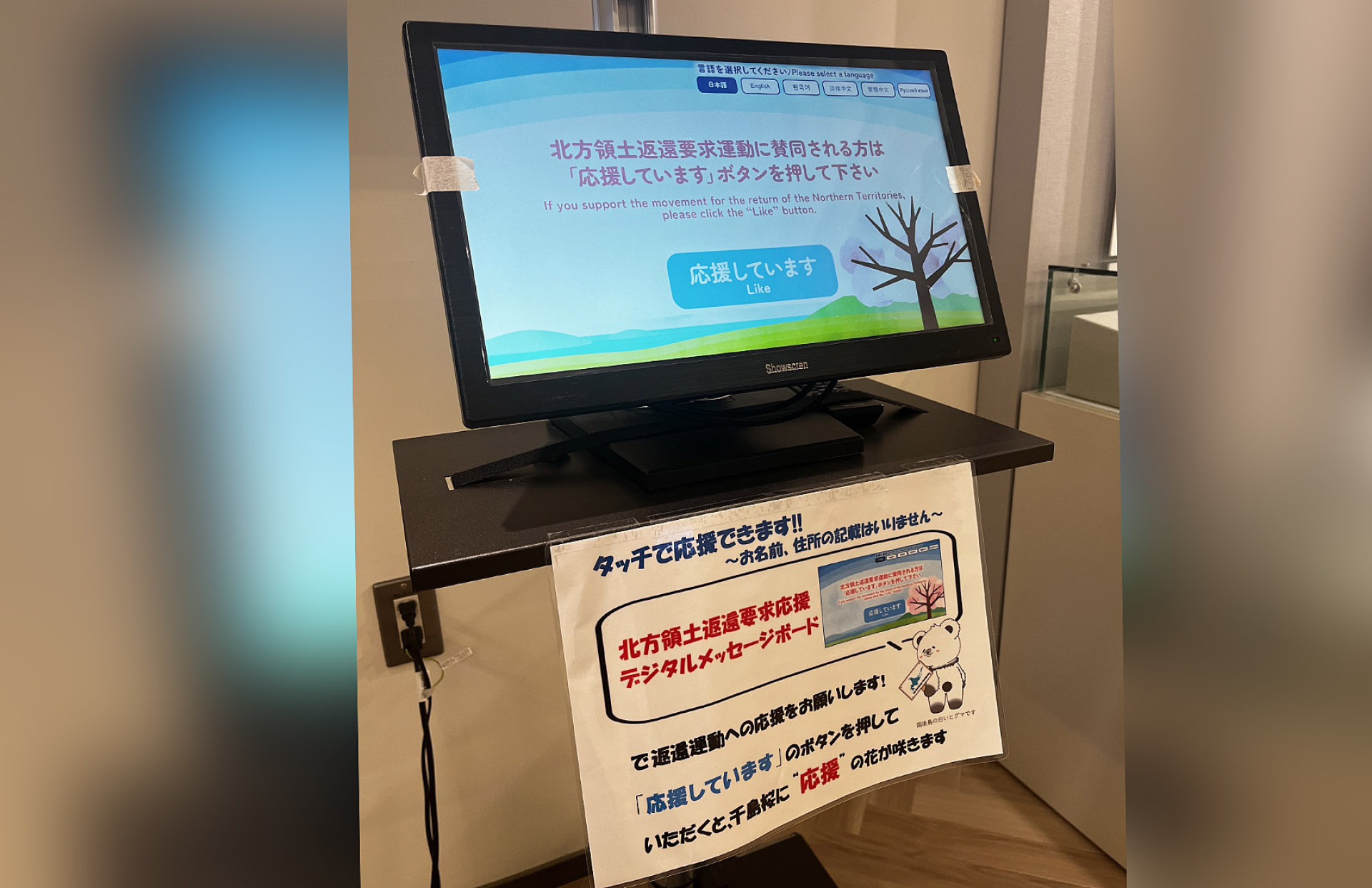

Across the room, a touchscreen offers a digital version of the same gesture — with a click, visitors can release a virtual cherry blossom petal onto a flowering tree on a monitor, signaling their support for the cause. Messages left behind appear in Japanese, English, Korean and, strikingly, Russian.

Nearby, a virtual quiz tests visitors on their knowledge of Russian culture, asking them to identify traditional Russian outfits and distinguish them from other European folk dress.

For the uninitiated, the juxtaposition can be disorienting. Russian culture, Japanese activism and a dispute over territory collide in a single, compact room.

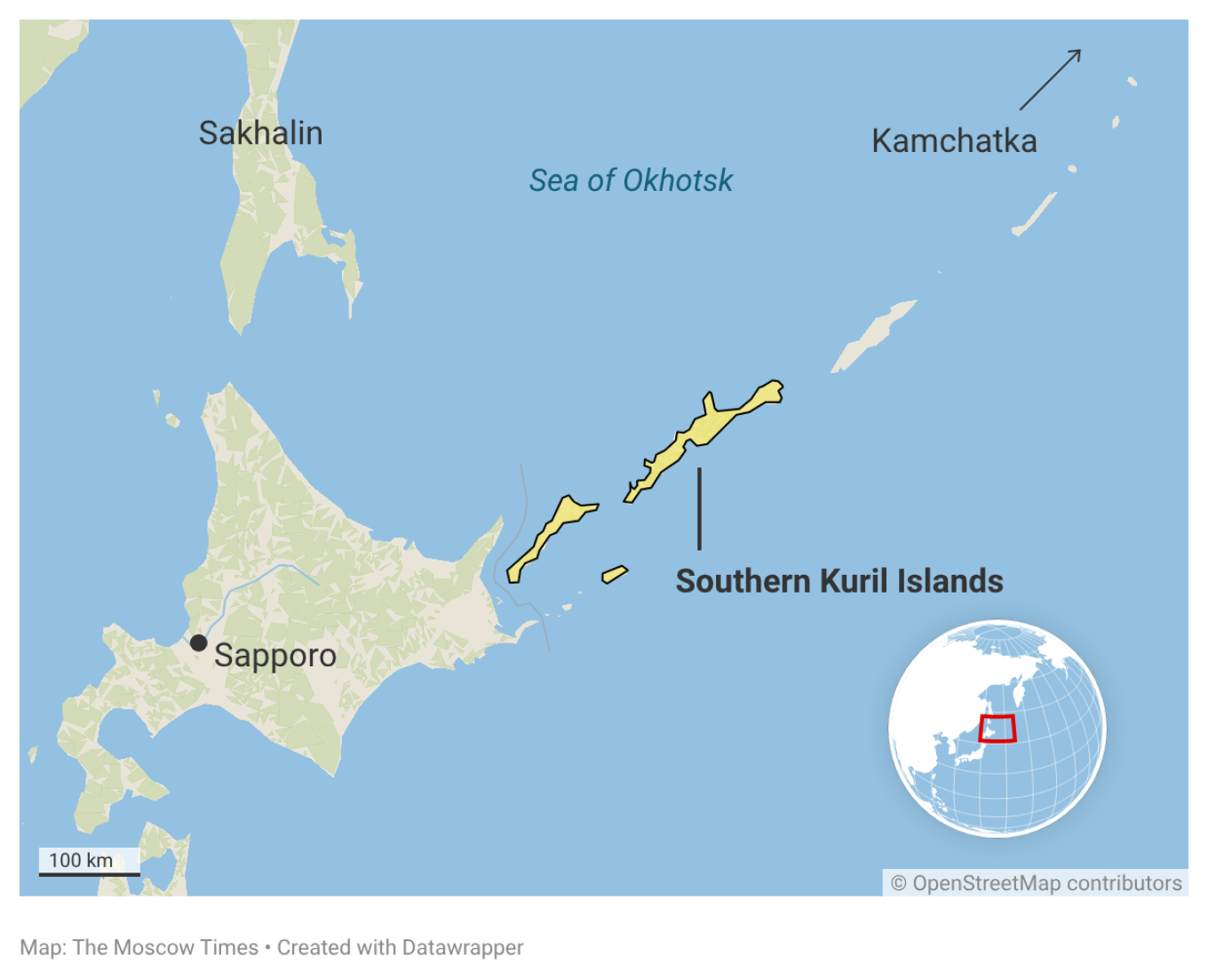

The “Northern Territories,” as they are known in Japan, are what Russians call the Kuril Islands. Or, to be exact, the four southernmost islands in the volcanic archipelago that stretches roughly 1,300 kilometers (810 miles) between Japan’s northern Hokkaido prefecture and Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula.

Today, the islands are administered by Russia as part of its Far Eastern Sakhalin region. Before World War II, however, the southern four were part of Japan, a status formalized in an 1855 agreement between Imperial Japan and the Russian Empire.

Japan maintains that the islands were illegally seized by the Soviet Union after it announced its surrender on Aug. 15, 1945. Russia argues that Allied wartime agreements, particularly the 1945 Yalta Agreement, entitled it to the Kurils in exchange for joining the fight against Japan and that the outcome of the war settled the matter.

Tokyo has long insisted that its sovereignty over all four islands be recognized before a peace treaty can be signed with Russia. More than eight decades after the war, the two countries still have not formally ended hostilities.

Many countries avoid taking an explicit stance on the issue, but notable powers like the United States and European Union back Japan’s position that the southern Kuril Islands are “occupied” by Russia and should be returned.

Now, Tokyo is “patiently urging” Moscow to come back to the negotiating table, but Kremlin officials appear uninterested.

The decades-long standoff between Russia and Japan did not entirely freeze contact. Beginning in the 1960s, the Soviet government allowed thousands of former island residents to visit family graves using only domestic ID cards. A visa-free exchange program followed in 1992, enabling Japanese and Russian citizens to make reciprocal visits intended to foster understanding among those most directly affected by the dispute.

“In those days, Japan and the late Soviet government, and then Russia, really tried to resolve the issue,” said Iwashita Akihiro, a professor of Slavic-Eurasian studies at Hokkaido University. “But they understood it would take time, so they began with human and cultural exchanges.”

“That was symbolic,” he told The Moscow Times. “It marked a goodwill period between Russia and Japan.”

Those exchanges carried particular weight for former Japanese residents of the islands, whose average age is now around 90.

“The Japanese feel a very strong obligation to look after the graves of their ancestors,” said James D.J. Brown, a professor of international relations at Temple University in Tokyo.

“There is also the idea of furusato, the idea of homeland in Japan, which is very strong,” Brown added.

Although the aging former islanders “recognize” they may never live on the southern Kurils again, he said, “at least for them there’s the idea that they want to be able to set foot on their homeland.”

Some momentum on resolving the territorial dispute appeared to build after former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe returned to power in 2012. Abe and President Vladimir Putin met repeatedly to discuss the matter, projecting a personal rapport and issuing statements that raised hopes of progress.

“Abe had a mission,” Iwashita said, referring to the former prime minister’s sense of political inheritance. Abe’s grandfather and father had both played prominent roles in shaping Japan’s post-war foreign policy, including on relations with Russia.

“This was a major task for him. He really wanted to achieve something,” Iwashita added.

In 2018, Abe told Putin that Japan would not allow U.S. troops to be stationed on the Kurils if they were returned, addressing a key concern of Russia’s given the heavy American military presence in Japan since World War II.

Still, a breakthrough proved elusive. Putin appeared less invested in resolving the dispute as Russia stood to lose little by maintaining the status quo, while Japan viewed the issue as central to its national interests.

“[Abe] tried absolutely everything. He couldn’t have done more to try and get a breakthrough with Russia,” Brown told The Moscow Times.

Some experts also questioned whether Japan could weaken Russia’s ties with China, an idea that informed parts of Abe’s strategy. Despite those doubts, the Abe administration, wary of China’s rise, pursued the approach.

“Abe didn’t listen to diplomats,” Iwashita said. “He began to think they were hindering negotiations.” As a result, talks leaned more heavily on economic advisers focused on possible joint business projects with Russia rather than on the territorial issue itself.

That strategy yielded little. By 2019, negotiations had effectively stalled, though visa-free travel and exchanges continued.

A year later, during the pandemic, Russia amended its constitution to make explicit that it would be illegal to give up any of its territory. While those changes were more focused on land Moscow annexed from Ukraine, they also applied to the Kuril Islands.

“That was a real slap in the face for Abe,” Brown said, noting the former prime minister’s attempts to meet Russia somewhere near a halfway point in negotiations, including ending the use of the term “occupation” in official statements about the islands.

And then, after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the visitation arrangements between the two countries came to an abrupt end. Japan imposed sanctions on Russia. In response, Moscow terminated the exchange program, closing one of the last remaining channels of human contact.

“We always had good relations on a human level, especially between Russians and people in Hokkaido,” Iwashita said. “But many former islanders had doubts.”

“The exchanges were good,” he continued. “But were they really a breakthrough for negotiations? Some former residents told me they weren’t sure they mattered.”

The Kremlin has since taken a harder line on the Kuril Islands dispute.

Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov said last year that there “should be no doubt” about who has a legitimate claim to the southern islands. Other Russian officials have said that a resumption of territorial negotiations and humanitarian visits depends on Japan abandoning its “anti-Russian course” — in other words, sanctions.

Iwashita said that Russia’s deepening ties with China and North Korea are forcing Japan to rethink its regional strategy, a shift that will be difficult to reverse.

“The international situation has changed completely,” he said. “Russia-China relations have been cemented. We no longer have any illusions about decoupling them.”

“Japan is a normative power,” Iwashita added. “After World War II, we integrated into the international community based on international law. That creates a fundamental divide with Russia today.”

Since October, when ultra-conservative Sanae Takaichi, a protégé of Abe, was elected as the country’s first female prime minister, Japan has moved to boost its military capabilities and even reconsider its long-standing non-nuclear status.

That once-unthinkable shift comes amid growing regional tensions, mainly with China, as well as perceived uncertainty over how Japan currently relies on the U.S. for defense.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has taken notice. At a press conference last month, he warned of what he called “unhealthy trends” in Japan, accusing the new government under Takaichi of seeking to remilitarize Japanese society.

Asked at the same press event about the prospects for resuming humanitarian exchanges, Lavrov, tellingly, ignored the question.

Takaichi recently said she will press Russia to restart the program allowing former island residents to visit their relatives’ graves.

“Resuming the visits is a humanitarian issue and one of the top priorities in Japan-Russia relations,” she said at an annual rally in Tokyo on Feb. 7 held to bolster public support for the return of the islands. “We will patiently urge the Russian side to resume them.”

For now, patience may be key.

“It’s a race of patience,” Iwashita told The Moscow Times. “If Russia were to say it was ready to return two islands, Japan would probably ease sanctions.”

“But no one believes Putin would do that,” he added. “So we’re in a deadlock. Russia doesn’t need Japan that much. Neither side has a strong reason to compromise.”

Brown, meanwhile, said that while many observers point to similarities between Takaichi’s political thinking and that of her former mentor Abe, she will likely have learned from the mistakes he made in his diplomatic outreach with Moscow.

“It seems that while on other issues she very much does follow in his footsteps, here she’s a bit different. She’s actually under sanctions from Russia for ‘unfriendly steps,’ for supporting sanctions,” he said.

“The fact, though, is that she’s going to be focused on China,” Brown added. “So it doesn't leave so much time for the relations with Russia.”

Following her Liberal Democratic Party’s historic election victory in Japan’s lower house of parliament this month, Takaichi now has more space to form and articulate a new way of political thinking about the Kuril Islands dispute and in relations with Russia more broadly amid a rapidly changing geopolitical context.

For former Japanese residents of the southern Kuril Islands, however, the shift may carry the bitter implication that as Japan grows more assertive, the chance of ever visiting the gravesites of their relatives again may be slipping further away.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.