ST. PETERSBURG — On a recent train from Moscow to St. Petersburg, half the coach was occupied by travelers from China.

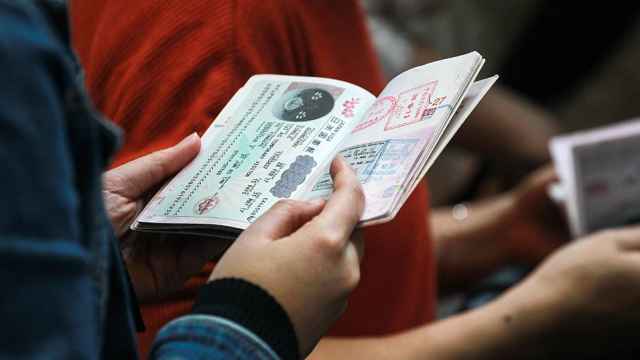

The group, made up of all ages, was on its way to Russia’s former imperial capital as part of an organized Chinese tour group, one of the first since Moscow opened its doors to Chinese nationals without requiring a visa last month.

The conductor, a stern woman in her 50s, paced up and down the aisle, muttering under her breath.

“Why did your compatriots laugh at me when I asked to check their passports again?” she asked the group’s guide, a Russian-speaking Chinese man. “Behave yourselves.”

The guide shrugged.

“These Chinese tourists have absolutely no manners,” the attendant said during a rest stop on the platform. “But of course, there are upsides. They even pay for hot water for some reason. Either that’s their custom, or they don’t know it’s free.”

After years of disruption caused by the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine, tourists from China are again flocking to Russia thanks to a new decree granting them visa-free entry.

The return of these high-spending tourists is being welcomed by Russia’s struggling tourism industry even as it revives familiar frictions with locals over cultural differences, overcrowding concerns and economic pressures.

The decree signed by President Vladimir Putin in December allows Chinese citizens to visit Russia for up to 30 days without a visa, mirroring Beijing’s September 2025 decision to grant Russians visa-free entry.

The new rules apply not only to tourists, but also to travelers arriving for business, academic or sporting events.

This change is expected to boost Chinese arrivals by around 30%, according to the Association of Tour Operators of Russia, with some experts predicting growth of up to 50%.

Many Chinese travelers are now choosing Russia over Japan, where tourism from China plummeted in December amid heightened diplomatic tensions over Taiwan.

Russian hotel bookings for Chinese travelers in the same month were up around 50% year-on-year, Subramania Bhatt, CEO of China Trading Desk, told The Moscow Times at the time.

While many Chinese visitors still flock to Moscow and St. Petersburg, their numbers are also rising in Russia’s Far East and northern regions, where they take northern lights tours and ride reindeer or dog sleds.

China has been Russia’s largest source of inbound tourism since 2014, when arrivals surged after the ruble collapsed following Moscow’s annexation of Crimea. A visa-free regime for small tour groups drove growth until it was suspended during the Covid-19 pandemic.

At its peak, the influx drew some resentment.

In 2019, Deputy Culture Minister Alla Manilova said Chinese tour groups were crowding out Russian visitors at the Catherine Palace near St. Petersburg. She proposed designating specific days for Chinese tourists, a suggestion the ministry ultimately abandoned.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the first year of the full-scale invasion in Ukraine saw tourist numbers collapse. Just 842 Chinese citizens entered Russia in 2022, when air travel was heavily disrupted by sanctions and war-related restrictions.

Tourism has gradually recovered in the years since. In 2023, Russia restored the visa-free regime for tour groups, sparking a renewed boom.

Roughly 1.2 million Chinese citizens visited Russia in 2024, rising to an estimated 1.3 million in 2025. About 2 million are expected in 2026 following the visa waiver.

The recovery has revived some of the same tensions.

In February 2025, residents of the Arctic city of Murmansk complained to local authorities about Chinese tourists’ behavior.

In response, Governor Andrei Chibis said these visitors were crucial for the local tourism sector.

Murmansk welcomed 26,000 Chinese visitors in 2024, a fivefold increase from the previous year, China’s Consul General in St. Petersburg said.

A St. Petersburg hotel owner told The Moscow Times that he was not particularly fond of hosting Chinese guests, whom he described as “loud and chaotic.”

“I much preferred working with Iranians or Europeans,” said the hotel owner, who requested anonymity for safety reasons.

Yet he welcomed visa-free travel as a way to fill empty rooms during the off-peak seasons.

“Right now, hotels in St. Petersburg are more or less full only from May to September and during the winter holidays,” he said. “The rest of the time, rooms sit empty. So the more visa-free tourists we get, the better.”

Security concerns have also weighed on demand, with some Chinese tourists canceling trips after the March 2024 attack at Moscow’s Crocus City Hall, said Polina Rysakova, a researcher of Chinese tourism in Russia.

Another challenge is a largely unregulated market dominated by Chinese tour operators, who often provide all-inclusive packages using Chinese payment systems and steer groups to commission-based shops.

Another part of the model involves charging Chinese tour groups for visits to public sites that are free or nearly free to access, with even rides on the St. Petersburg metro marketed as a “unique cultural experience” and sold at a premium.

“There’s no secret here. Chinese tourists are mostly handled by Chinese operators. Russian firms get very little,” the owner of a St. Petersburg travel agency told The Moscow Times.

Despite these issues, officials maintain that Chinese tourists are vital to the Russian economy.

Alla Salayeva, a lawmaker on the State Duma’s Tourism Committee, said the influx boosts state revenue and helps develop tourism infrastructure.

Some Russian operators hope the visa waiver will help them attract younger, independent Chinese travelers, who tend to book services locally rather than through group tours.

“I agree with the forecast of around 30% growth,” the St. Petersburg travel agency owner said. “And I do think Russian tour operators have a good chance of attracting these independent travelers.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.