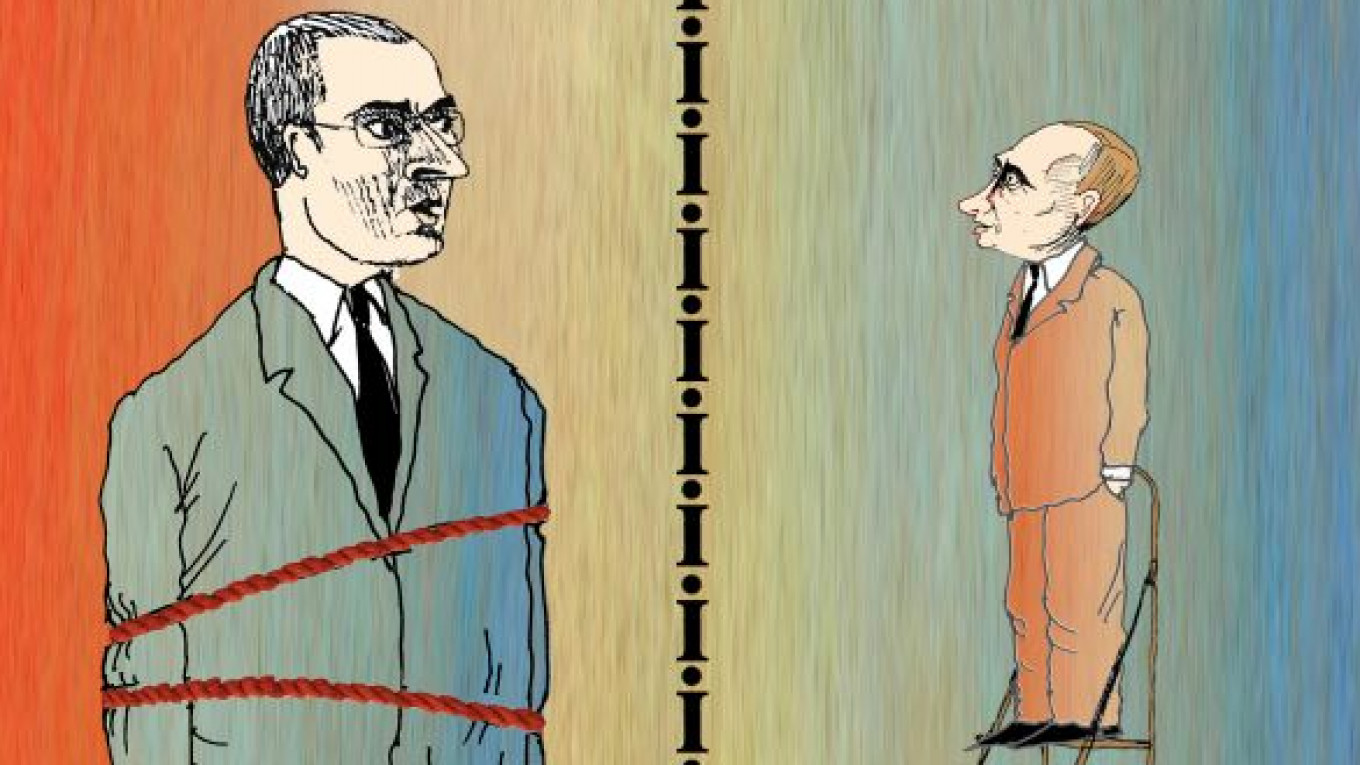

President Vladimir Putin's decision to pardon former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky from prison is clearly the top political event of the year.

Khodorkovsky had become one of Putin's central problems, and he knew he had to resolve it eventually. Putin had to decide if he should free Khodorkovsky next fall, when his prison term would have expired, or bring additional charges against him and keep him behind bars even longer. Putin chose a third option: to free him now on terms worked out with Khodorkovsky himself and German mediators.

Khodorkovsky enumerated the conditions for his clemency during his first interview in Berlin Sunday. First, he will not return to Russia for an indefinite period of time. Second, he will not take part in politics. Third, he will not seek legal claims to former Yukos assets that were essentially nationalized by the government and "auctioned off" to Rosneft. Fourth, he will not finance the opposition. Khodorkovsky always did keep his word, and will no doubt uphold his end of this bargain as well.

Khodorkovsky is a man of great courage and personal honor. For 10 years, he refused to admit guilt on any grounds for two reasons: One, he is not guilty, and the government's case and convictions were a complete fabrication. Second, the authorities could have exploited his admission of guilt to imprison hundreds of other former Yukos employees and members of various foundations that Khodorkovsky had established. That is why he agreed instead to plea for clemency, which is not an admission of guilt.

Putin covered all of his bases and has strong collateral to ensure that Khodorkovsky will never violate the terms of the clemency agreement. Putin could apply additional pressure to those already jailed over the Yukos affair, or he could arrest new figures if Khodorkovsky were to become active in politics or file lawsuits in Western courts demanding the return of his assets or lost fortune. Khodorkovsky will never do anything that could harm vulnerable former colleagues and associates who remain behind in Russia.

Right now, the most important thing for Khodorkovsky is his mother, who is being treated for a serious illness in Germany, his father and other family members, and he will devote all of his time to them in the coming months.

He became stronger and wiser during his years in confinement and has displayed heroic courage and self-composure amid the unprecedented campaign of state repression against him. As someone who has known Khodorkovsky for many years, worked on the governing board of his Open Russia foundation and maintained contact with him all of these years, I am very happy for him and his family.

Khodorkovsky maintains a discreet and low profile position with regard to Putin and Russian politics. He does not mince words and is uncompromising and firm in his judgments. At the same time, however, he takes a balanced view of things, which might disappoint the more radical members of the opposition. Khodorkovsky advocates dialogue, compromise and restraint. His views are not those of a radical but of a responsible politician who is aware of the effects of every one of his words and actions. He stands for Russia's integrity and development, without any desire to exact revenge. This can help change the overall tone of the discussion in Russia from one of hatred and confrontation to a new, civilized debate about Russia's present and future course.

That is how he sees his mission when he speaks of becoming more involved in civil society. Political analyst Alexander Rar was not far off the mark when he said that he sees Khodorkovsky as a new symbol of moral conscience for Russia, much like writer and dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn or human rights activist Andrei Sakharov were during the Soviet Union. Khodorkovsky will fight to win the release of political prisoners and try to build a stronger and more responsible civil society in Russia. To be sure, these tasks are not new to Khodorkovsky. For 15 years, he has donated money to dozens of educational and charitable projects and has become one of the country's largest philanthropists.

Now that Khodorkovsky is free, it will make it much more difficult for the Kremlin to concoct new fabricated court cases like the one against Yukos. His authority will help move Russia toward greater freedom, democracy, open society and the rule of law. Ten years ago, Khodorkovsky's arrest changed Russia for the worse. Now his release will change it for the better.

Vladimir Ryzhkov, a State Duma deputy from 1993 to 2007, hosts a political talk show on Ekho Moskvy radio and is a co-founder of the opposition RP-Party of People's Freedom.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.