Catherine Merridale, a historian of Russia and the former Soviet world and an award-winning writer of nonfiction, has published “Moscow Underground,” a detective novel set in Moscow in 1934.

She spoke to Pushkin House about the process of writing her first fiction book and the power of fiction to explore the Stalinist period, creating complex characters and navigating contested historical legacies in her book.

Pushkin House: Why did you decide to write ‘Moscow Underground’?

Catherine Merridale: I always dreamed of writing fiction, even before I became a professional historian. I love the adventure of historical research, but it has been impossible to do serious work in Russia for some years now — or even to go there. Instead, I took the opportunity of writing from my imagination and it's been an adventure of a different kind and very satisfying.

PH: How did your earlier research and your background as an oral historian help you construct the book, its plot, characters or settings?

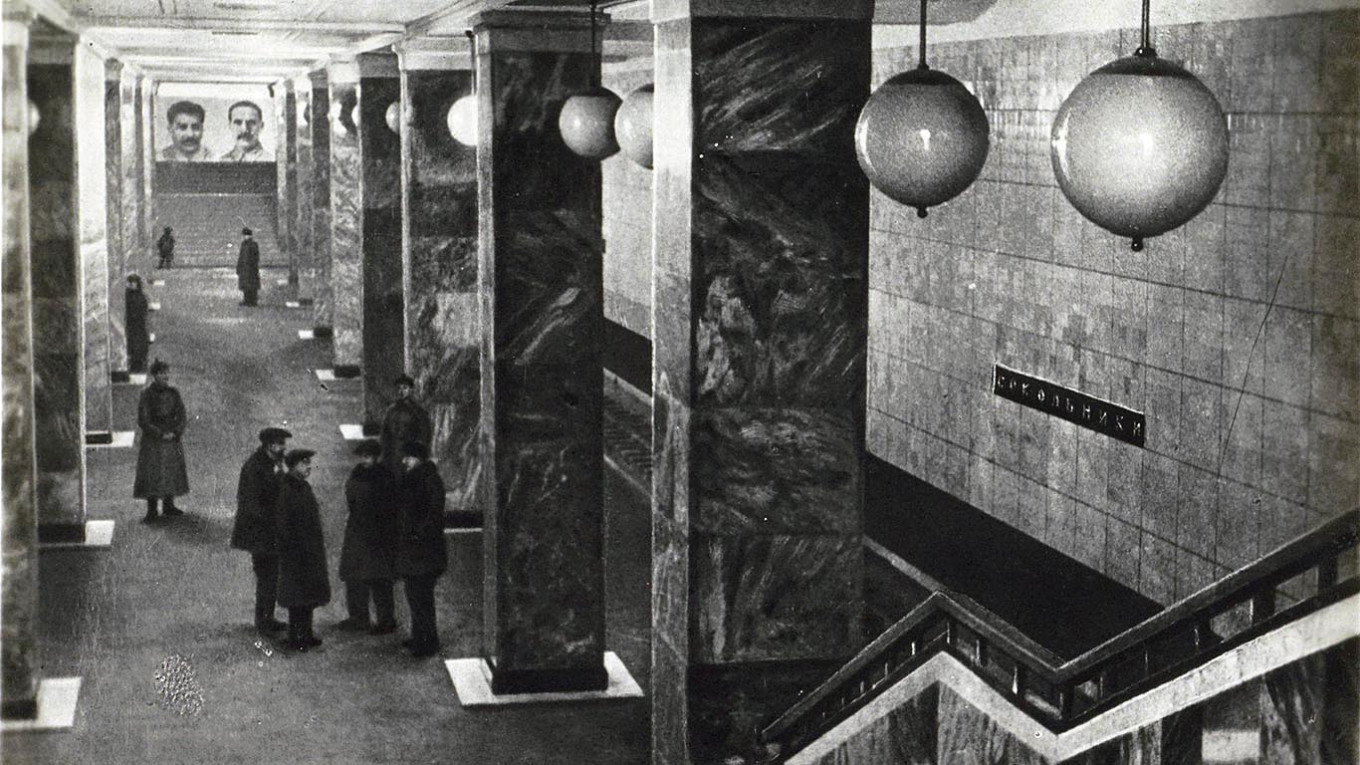

CM: Though ‘Moscow Underground’ is a work of fiction, I conceived it by imagining an old man (Anton) telling me his story. My faithful tape recorder whirred, at least in my imagination, as it has done thousands of times. I could hear real voices as I tried to choose my words, and countless historical shadows stepped in and out of the story as it unfolded on the computer screen. As for the settings, I have walked almost every street in the book and explored the underground tunnels myself. Old photographs have helped as well, including the collections in Russian archives that I also explored for research. In many ways, the Moscow of 1934 is more real to me now than Putin's current grim pastiche.

PH: ‘Moscow Underground’ explores the layers and labyrinths of history — not just deep in the Moscow Metro tunnels, but in the manipulation of the past under Stalin. This feels like a resonant theme throughout the book. Can you tell us more about it?

CM: The Metro is a perfect place to think about deep pasts. Futuristic and ambitious though it looks, it belongs in the kingdom of the dead. All dictatorships manipulate history and Russia’s rulers have been doing it for a very long time. When I was writing my history of the Kremlin, ‘Red Fortress’ [winner of the Pushkin House Book Prize 2014], I followed the process through the stories of buildings. But all physical evidence is awkward stuff. The bones of the unavenged can lie silent for years, but they are always in the earth, as I learned in the 1990s when I visited Sandormokh with the indefatigable Yury Dmitriev.

It may be relatively easy to change a history syllabus or to build a vulgar monument but if you dig deep - metaphorically or literally — the past is bound to speak. Then I discovered that the Soviet government had employed a team of historians and archaeologists to vanquish the old relics that were holding progress up. They wanted to defeat the past, to triumph over it. They only half-succeeded. I found the image irresistible.

PH: Did you discover any new or surprising facts while you were working on the book?

CM: I loved reading about the archaeologists. They took themselves very seriously, but it must have been delightful to find out that the future of the world-leading Moscow Metro hung on a cellar full of wine that everyone had forgotten about. The story of the Metro is full of surprises like that.

PH: How did you find the process of writing your first fiction book? Do you feel that fiction, and the detective genre, has a capacity to explore this period of history in a way that nonfiction does not?

CM: The hardest thing was abandoning my inner professor. When I started writing, I used the third person. That was fatal; I kept writing facts. So I let Anton’s voice take over from mine and everything was instantly a lot more natural and way more interesting to write.

From then, my deep familiarity with primary sources was actually a source of freedom. I did not have to rely on other people’s interpretations or their choice of language — I knew, from years of immersion in the period — exactly what words and images formed the currency of Stalin’s Moscow. I was writing from inside the period; I was actually right there, gazing into the darkness and uncertainty of Stalin’s tyranny — looking forwards at it, in fact — as if from Anton’s time, not knowing what might happen next but sharing his disorientation at the speed of revolutionary change.

It's true that historical nonfiction writing is also a creative process; selective, constructed and shaped. But its goal is to answer questions and address today's intellectual puzzles; it is a dialogue with the present. Only fiction takes the reader back into the living past. When I was working on this book, I wasn’t in my writing room; I was in Moscow with my characters. I saw the chaos and the mud, the trams stuffed with disgruntled laborers, the shops with their empty shelves and the glint of the Kremlin’s golden domes. I smelled the sweat, I heard the engines and I breathed in stale makhorka [tobacco] smoke.

There is a crucial drawback, though. No one has to read this stuff to get through their exams and no one in their right mind wants to live in Stalin’s time. The book must be inviting or it will stay on the shelf. That’s where detective fiction scores: it has a structure, it has momentum and ultimately it's almost always reassuring. Quite unlike real life, perhaps, but no one ever minds.

PH: Do you have a favorite character in the book? Or which character was the most interesting to write?

CM: I like Misha the chef, of course; his world is purely pleasurable. But two other characters intrigued and surprised me. Anton’s father, Mark Belkin, started life as an artist of the Red Revolution. But as my story grew around him I began to feel the old man's frustration about Stalin's bureaucratic, stultifying culture. Meanwhile, Viktoria Maksimovna — Vika — turned out to have a past that made sense of her strange career. She is the most complex of all my main characters, if not the most attractive, and there is a lot more to be said about her in a future book.

PH: Can you tell us some more about Vika? She's clearly a complex person with a backstory, yet she is also an NKVD officer who facilitates ideological violence. She seems like a controversial or polarizing character to write about in today’s context. How did you approach this? Did you draw on any real people who you interviewed?

CM: Vika really wrote herself. She isn’t based on anyone. As with Anton, she belongs in a certain time and place and I certainly wouldn’t endorse any of her choices, including her ideological commitment to the Cheka. But I let her have a family whose opinions were different, who compromised and even endangered her, and I trapped her in a situation from which there were no easy escapes. Then she did what she had to do, often to my horror.

In all my writing about Stalinism, and through all the interviews I conducted, I was conscious of one real privilege: I had never faced the dilemmas of that time. It's easy to assume that ‘we,’ meaning comfortable Western Europeans and the British above all (because we were not invaded in WW2), would always be on the side of the angels, the good side, fighting against tyranny and never betraying our humanity. But would we? If there were a real threat to my family, to my life? Would I?

The truth is that we cannot know, and to assume a moral superiority, to assume any certainty at all, is to disdain the very people who survived and did the best they could (and possibly did better than I might have done — I am so glad not to have known). I am not condoning tyranny, violence or corruption — far from it. On the contrary, it is only by constantly examining what we do that we can face the severe tests of our own generation and find a way through that some future interviewer will not blithely condemn.

PH: Your book is split between 1934 Moscow and flashbacks to 1919-20 Ukraine, turbulent and traumatic times which have highly politicized legacies today. There’s quite a responsibility when telling a story of those times, and the people who lived through them, with sensitivity and nuance. How did you deal with this when writing the book?

CM: I began writing the book in 2021, before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The illegal and criminal annexation of Crimea had already happened, so I was very much aware of the continuing conflict, but Ukraine, unfortunately, was not the major preoccupation of its European neighbors that it has since become. At this early stage, I wanted Anton and Vika to have experienced the trauma of the Civil War because it was crucial to the mentality of their generation. I knew Kyiv, I knew the south (and, indeed, Sevastopol and Yalta), so I set their war there. At the time, I also knew I would be touching the raw nerves of nationalism and Great Russian chauvinism but they, too, were part of what I needed to explore.

After Russia’s unprovoked attack on Kyiv in February 2022, I carefully reconsidered my choice. I also wondered about using Ukrainian place names instead of Russian ones. But Anton is not me and nor does he live in the present century. His voice and his views belong to a Russian — a Soviet — of the 1930s and not to a British academic and writer. To some extent, he is an unreliable narrator, a biased witness, but his thinking also tells us a great deal about Russia’s misrepresentation of Ukraine and the violence that has followed from it.

I think this is a further example of the difference between writing history (nonfiction) and a story (fiction). The former is essentially a dialogue with the present, however deeply it engages with previous generations and their worlds. The latter, though written in the present, strives to immerse both author and reader in a complete and credible past. Including the questionable bits.

PH: Were you inspired by any other detective writers or books?

CM: Oh, certainly! As a Ph.D. student, I read Umberto Eco’s ‘The Name of the Rose’ and Martin Cruz Smith’s ‘Gorky Park,’ both of which, in different ways, helped to inspire ‘Moscow Underground.’ But I’ve remained an avid reader of detective fiction, especially if it creates a credible world for its characters. My Edinburgh is heavily influenced by Ian Rankin’s ‘Inspector Rebus,’ for instance, and my Venice by Donna Leon's ‘Brunetti.’

PH: Will there be a sequel?

CM: Yes. Anton is already on another case. The stakes are higher, too, because the political atmosphere is darkening and this time his most treasured friend is in the firing line.

This article was originally published by Pushkin House. For more information about the book, see the Pushkin House Bookshop site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.