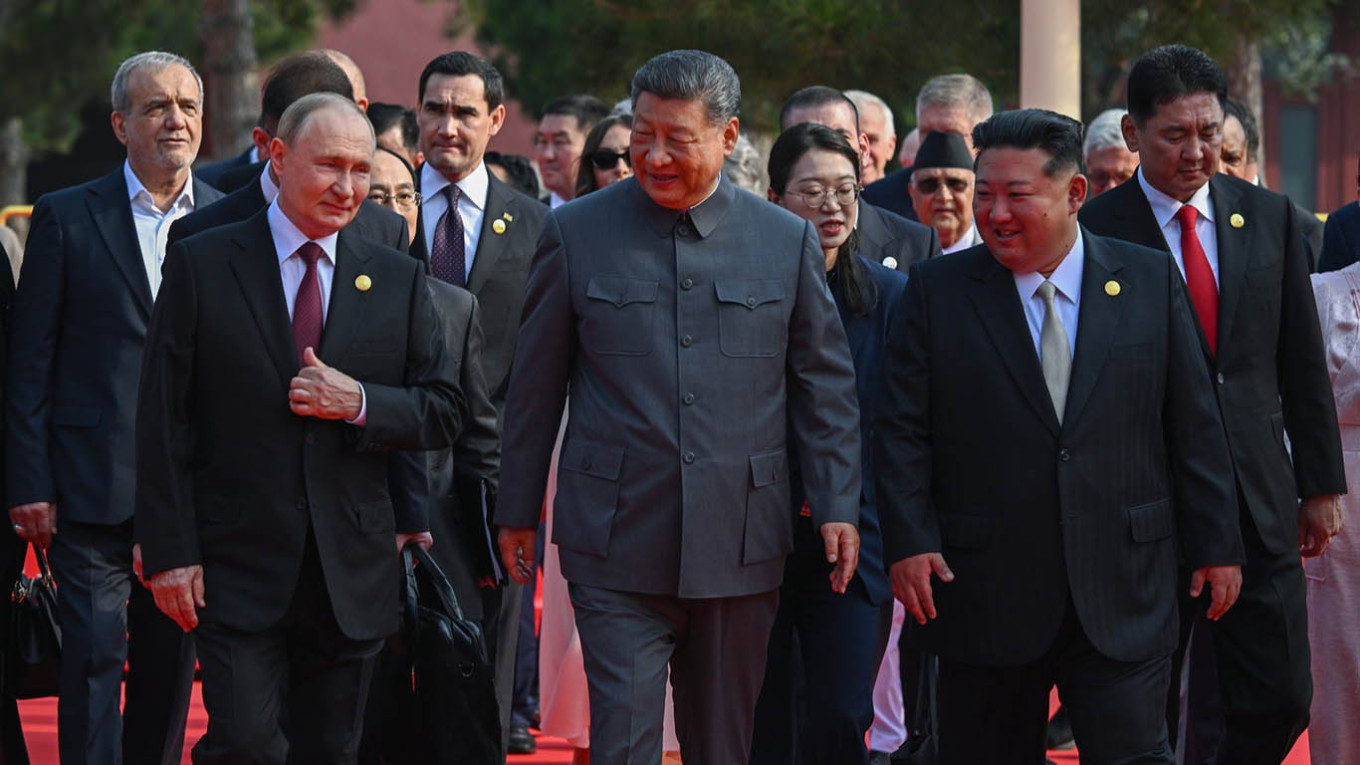

The aging autocrats walked side by side, leading a procession of foreign leaders to watch a military parade in Beijing.

Then, in a surprisingly candid moment, a hot mic caught President Vladimir Putin and Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping discussing methods for prolonging human life.

“Human organs can be continuously transplanted,” Putin’s translator was heard saying. “The longer you live, the younger you become, and [you can] even achieve immortality.”

For the Russian president, the topic of mortality drives to the heart of perhaps the greatest vulnerability of the autocratic system he has constructed: When he is no longer in power, will it all fall apart?

In the 25 years since he was first elected as president, Putin has remade the Russian political system in his image.

The ruling, pro-Kremlin party, United Russia, occupies 315 of 450 Duma seats and holds the vast majority of regional appointments. Elections are neither free nor fair, according to human rights observers, and constitutional changes he oversaw in 2020 allow Putin to remain president until 2036, when he will be 83.

These facts lead many analysts to believe that Putin would not willingly leave office. Instead, if the Russian president were to pass away or become incapacitated, a series of political dominos would begin to fall outside of his control.

First, Russia’s prime minister would step into the presidency. That would make Mikhail Mishustin, a 59-year-old former tax official who has served in the role since 2020, the country’s leader — but only temporarily.

According to the Constitution, the Federation Council should call elections to determine a new president within 14 days.

This is where the process would get muddled. As far as analysts know, Putin has not hand-picked a successor.

“If Vladimir Putin dies suddenly or with a week or two weeks’ worth of sick notice, there’s going to be a ton of pressure to not screw things up to avoid a Time of Troubles,” said Julian Waller, a professor at George Washington University and a Russia researcher at the think tank CNA.

“You don’t want the 90s back again. You don’t want the Russian Civil War,” he said.

Such a situation could see the emergence of numerous contenders jockeying to head the country’s government. Mishustin’s appointment as president is no guarantee of his likelihood to be elected, experts say, and the electoral process could serve to legitimize a hand-picked successor.

But there is a fundamental paradox in the makeup of Putin’s inner circle: many of his potential replacements are old, too.

Figures like Defense Minister Andrei Belousov, former Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin have all at some point been named by analysts as potential successors. The youngest among them is 66 years old.

“The baton should have been passed a little while ago,” Waller said. “They failed to do so, and now there’s been kind of a rush in the last couple of years — really since the war — to try to freshen up the blood of the Russian elite.”

Instead of coming from Putin’s inner circle, Waller said that a successor could emerge from a younger crew of officials appointed during the war in Ukraine.

People like Alexei Dyumin, the 53-year-old State Council secretary and former Putin bodyguard, or Dmitry Patrushev, the 47-year-old deputy prime minister for agriculture and son of the former Security Council secretary, would likely uphold the system Putin has created but not be burdened by their age.

Officials may also attempt to install someone who is uncontroversial and malleable to the desires of political elites.

“It is possible that the person who succeeds Vladimir Putin is not the most powerful person in the political order, at least for that immediate period,” Waller added.

There are few precedents in modern Russia for the kind of chaos such a changing of the guard could bring.

The most recent major crisis to face the Russian regime came in 2023, when Wagner mercenary leader Yevgeny Prigozhin launched an attempted military revolt that brought his fighters from Rostov-on-Don to Moscow’s doorstep.

The Russian authorities were caught on the back foot. Public messaging throughout the mutiny was scarce, and the Russian leadership appeared uncertain how to respond.

Putin’s death could prompt a similar response among the authorities and the general public, said Margarita Zavadskaya, an expert on Russian politics at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

“His sudden absence would be shocking, but people are most likely to adopt a wait-and-see attitude rather than to mobilize against or in support [of the new leadership], or to commemorate [Putin],” she said.

In the tradition of Soviet leaders before him, Putin’s death might not even be announced immediately so as to allow time for crafting a response, Zavadskaya suggested.

Factions outside of the Kremlin and the upper tier of elites are unlikely to play a role, she continued, and the perennially fractured military would need a strong incentive to throw its weight behind a challenger.

While democratic opposition groups would likely make a lot of noise to mobilize anti-Putin Russians, they have been largely exiled and relegated to political irrelevance due to the Kremlin’s massive curtailing of civil freedoms.

In any event, Zavadskaya said that the only certainty about a post-Putin Russia is that it “is unlikely to become a democratic regime.”

For his part, Putin appears satisfied that the legacy he is forging with his war on Ukraine and standoff with the West will offer its own kind of immortality.

In a press briefing with Xi this month, Putin invoked Russia and China’s shared “heroic feat” in winning World War II, and hailed an emerging world order in which, like in the past, their countries are not beholden to the West.

Relations between the two countries “have reached the highest level in history,” Putin noted, “being self-sufficient and independent from internal political factors or momentary global agendas.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.