Valentina is a “kind, modest” 14-year-old girl with blonde hair who enjoys dancing.

Dima is a “calm … responsive” 10-year-old boy who likes drawing, puzzles and playing sports.

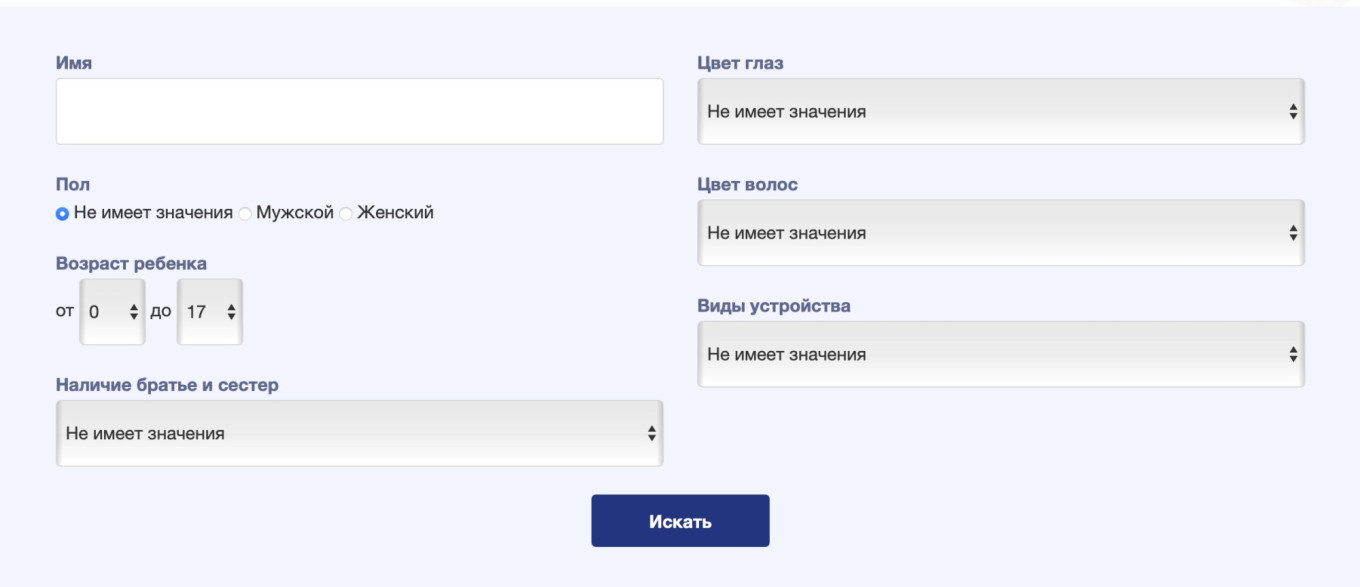

They are among the 294 young Ukrainians listed on an online adoption database published by authorities in the self-proclaimed Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR). Prospective parents can sort through them according to their age, sex and physical characteristics like hair and eye color.

Experts told The Moscow Times that it is common for children to be displayed in databases like this. Many legitmate adoptions are arranged this way, although forcefully transferred Ukrainian children have been found in Russian databases.

But the new website could be a sign that LNR authorities are operating a forced adoption program independently from Moscow, something that could further complicate efforts to reunite these children with their families.

As many as 35,000 Ukrainian children have been taken from care institutions or forcibly separated from their families and are still held in Russia or occupied Ukrainian territories since the full-scale invasion in February 2022, Ukrainian officials say.

Only 1,509 have been returned, according to the Ukrainian NGO Bring Kids Back.

The forcible transfer of children with the intent to destroy, even partially, a nation or ethnic group is considered an act of genocide under the 1948 Genocide Convention.

United Nations investigators have described Russia’s practice as a war crime. In 2023, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for President Vladimir Putin and his children’s rights commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova over the deportations.

The Kremlin justifies the program with claims that it is removing the children from danger.

If the LNR is operating independently of the federal Russian program, it could further complicate efforts to identify and return children to their families, experts said.

Even before Russia unilaterally annexed the region in 2022, the separatist governments in Donetsk and Luhansk were only acknowledged by other breakaway states, Russia, North Korea and Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime.

“We don’t know whether the [LNR] is moving these children under Russia’s statutory code or their own. Where did these children come from? Are they from the [LNR] or other areas of Ukraine?” Nathanel Raymond, executive director of Yale's Humanitarian Research Lab, told The Moscow Times.

“The [LNR], like the [Donetsk People’s Republic], doesn’t do anything without Russian permission and coordination. So it would be highly irregular for them to do this without the direct involvement and approval of the Kremlin,” Raymond continued.

Karolina Hird, an analyst researching the illegal deportations of Ukrainian children for the U.S.-based Institute for the Study of War, said that the LNR-run database could serve to obscure when children are being transported to Russia, creating the impression that they were being placed with families in the region.

“What matters is where these kids are going. If these kids are transported to Russia, the law is clear,” she told The Moscow Times. “If they are adopted within LNR or DNR it’s more complicated because that is within Ukraine’s international borders.”

The Moscow Times was not able to verify whether the LNR database operates independently.

Russia’s main database of children available for adoption is run by the federal Education Ministry and is connected with two secondary databases.

Since Russia declared its annexation of Ukraine’s Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions in September 2022, children from these regions started to be included on these centralized databases. Before that, they were directly placed with families in Russia.

Children have been taken from institutional care facilities as well as separated from their parents in filtration camps. The children's profiles do not explain why they are not under the care of their parents.

The similar backgrounds in the Luhansk database’s photographs suggest the children may have been living in the same camps or group homes. After a Ukrainian NGO drew attention to the website, many of the profile pictures of children in what looks like the same summer camp were taken down.

Their ages range from 16 to toddlers and even a baby less than a year old, who is described as an “active” child who smiles when looking at adults.

For the younger children, forced adoption means they will have no memories of anything other than living in Russia.

Under Russian law, adoptive parents are able to change children’s full names and their place of birth, effectively erasing any record of the life the child once had and making it much harder to locate them and return them to their families.

Older children are often sent to re-education camps, where Ukrainian officials and independent activists say they are indoctrinated into hating Ukraine and loving Russia.

Ukrainian officials say that children who have gone through this program have been sent to fight against their birth country once reaching fighting age.

Mykola Kuleba, founder of the Save Ukraine NGO, warned that the children on the platform were vulnerable to sexual and labor exploitation, as well as to potential trafficking for organ harvesting.

“Let’s be clear: this is not adoption. This is not care. This is digital child trafficking, masked as bureaucracy,” he wrote on social media.

The Russian Education Ministry and Luhansk Education Ministry have been approached for comment.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.