When declaring martial law in Russian-occupied Ukraine last month, Russian President Vladimir Putin also handed special powers to regional authorities across Russia and created an influential new government body that is charged with coordinating supplies to the military.

To the average Russian, these changes might look trivial. But, step by step, Putin is laying the foundations for a fundamental restructuring of Russian politics.

As a result of decrees signed by Putin, regional governors can now limit civil liberties — and the federal government in Moscow has the scope to move the economy to a war footing. Different regions have been given different powers. For example, the authorities in annexed Crimea can temporarily resettle residents and put restrictions on those entering and exiting the region. In Moscow, the authorities can limit the movement of vehicles. Following October’s successful attack on the Crimean Bridge, infrastructure defenses are also being reinforced all over the country.

Let down in Ukraine by his natural allies, the security services, Putin is now looking to senior figures in the civilian bureaucratic apparatus. And the Coordination Council, the government body which Putin set up in mid-October and which held its first meeting last week, is headed by Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin.

Essentially, Putin has directed the Council to transform the economy so it can sustain the needs of the Armed Forces in Ukraine. Specifically, it will set targets for supplying the army; control prices, suppliers and logistics; and build and equip barracks and other military facilities.

Decisions taken by the Council are not only binding for officials, but also for businesses. Mishustin has already announced that much of Russia’s manufacturing sector, including small businesses, will be required to produce equipment for the army.

Judging by the scope of its powers, the Council will — to some extent — supersede even the Russian government itself. In the thick of the fighting in Ukraine, Putin is effectively carrying out political reforms and restructuring his power vertical — in an attempt to win the war. In his first meeting with Council members, Putin said that the time had come to “update” Russia’s system of government. “This is precisely why… this Coordination Council was created,” he told the assembled group.

Rebuilding power structures in wartime like this is a de facto admission that the Defense Ministry has failed in its goals in Ukraine. Putin bet heavily on military success at the start of the war, but this never materialized.

Russian soldiers have complained for months about insufficient supplies of weapons, ammunition, medicine and rations. Things failed to improve even after Putin replaced veteran Deputy Defense Minister Dmitry Bulgakov in September. And when mobilization was announced at the end of September, the Defense Ministry’s failures were put on display for all to see.

From now on, civilian officials will be tasked with supplying the army. In a bottom-up decision-making process resembling that used during the coronavirus pandemic, the onus will be on the federal government and local governors, who have a better understanding of their local areas. In other words, the responsibility for unpopular new measures will be delegated to regional officials. Failure will be punished by Putin himself — by humiliation in front of the TV cameras.

Putin apparently believes that Russia’s handling of the pandemic was a success, despite the country having one of the world's highest excess death numbers. The key — and possibly sole — criterion for judging this “success” is that coronavirus did not impact Putin’s personal popularity or threaten his grip on power.

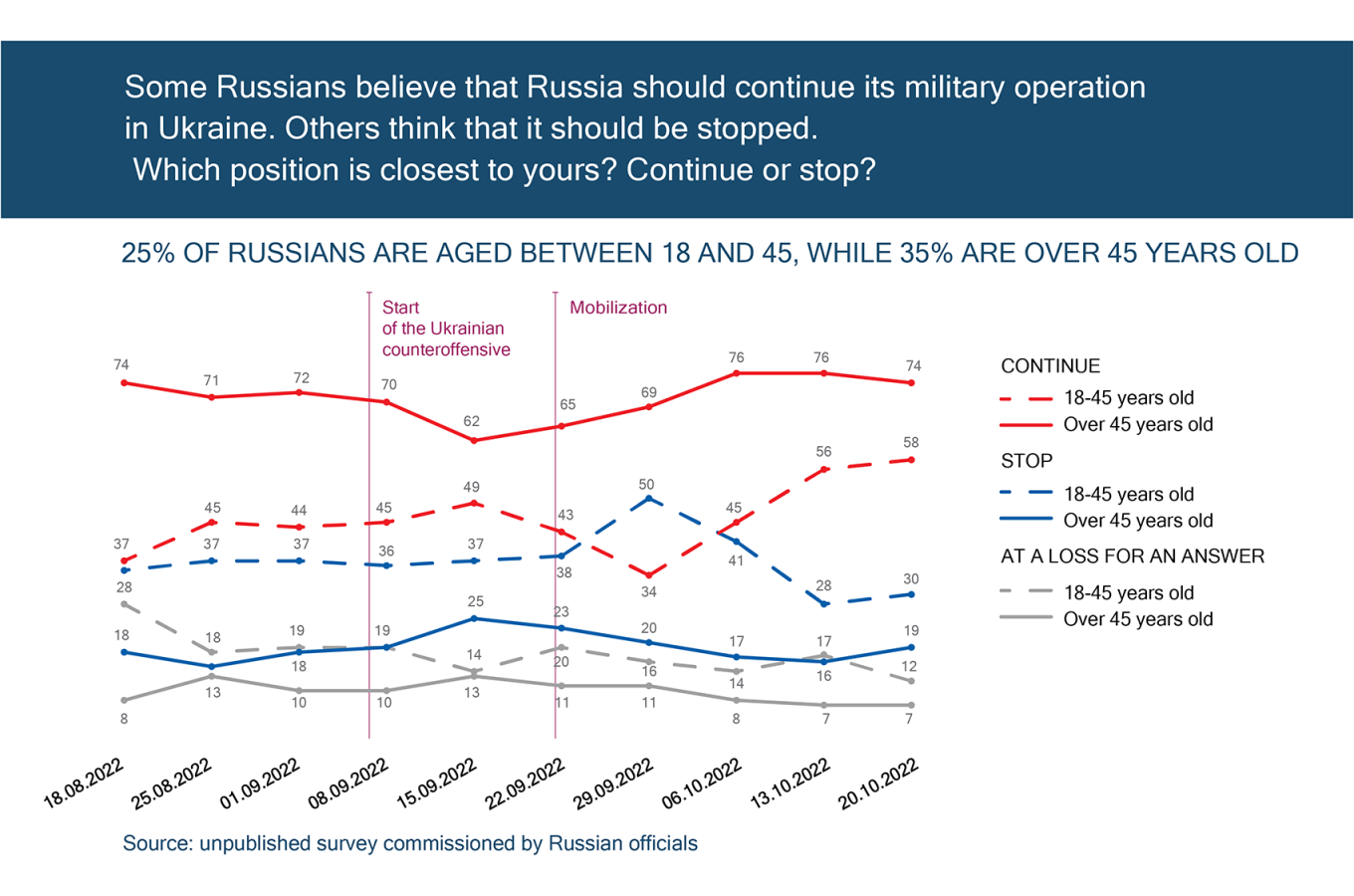

Of course, Putin closely monitors Russian public opinion when it comes to the war. In a copy we obtained of an unpublished survey for officials that was carried out by a Kremlin-controlled polling agency, the results reveal the Ukrainian counteroffensive and Russia’s mobilization announcement have shaken the public’s faith in what the Kremlin calls its “special military operation.”

The survey suggested 68% of Russians believe the war should be continued and 22% that it should be halted. Although, it’s worth remembering that independent polling experts have warned about trusting the results of surveys when those publicly opposing the invasion can be jailed under wartime censorship laws.

In line with Russian propaganda that likens the current conflict to World War II, some state-run media outlets have compared Putin’s new Council with Stalin’s State Defense Committee, which was established in 1941. The committee, which remained in operation until Nazi Germany was defeated four years later, helped transform the Soviet economy and its decisions were binding for all state bodies.

One high-ranking Russian official said he was certain that, regardless of politics, Putin’s decision is the right one in terms of management effectiveness.

“After mobilization was announced, the scale of the task was extraordinary,” he said. “We need to calculate everything correctly: what people at the front will eat, what they will wear, etc.”

As a part of this, any Russian businesses that can be repurposed will be obliged to produce supplies needed by the Armed Forces. “For example, companies that are currently sewing car seat covers can start sewing military uniforms,” the official said.

Others, however, are less sure. Sergei Aleksashenko, a former deputy finance minister, said it’s too early to say whether Russia is mobilizing its economy. He told us there were never any market principles in state defense contracts. “The Defense Ministry twisted arms, issued orders and set its prices,” he said.

The Coordination Council’s membership is composed of more civilian officials than military ones. Apart from Mishustin, it includes Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin, deputy prime ministers and senior financial and economic managers (with the notable exception of the head of the Central Bank). Members from the so-called siloviki include the heads of the Defense Ministry, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Foreign Intelligence Service, the National Guard, the Interior Ministry and the Emergency Situations Ministry.

Until recently, civilian officials were focused on maintaining economic stability and working to maintain the illusion among ordinary Russians that the war was something far away with few consequences for day-to-day life. Russia’s relatively successful insulation from the major economic shocks of sanctions — thanks to the efforts of the Central Bank and the government — has been key to preserving Putin’s popularity.

But now, the president is pushing these same civilian officials to the fore. They are charged with solving the army’s supply problems and raising troop morale — by improving conditions for soldiers as well as ensuring that social benefits are awarded to their families and that they receive promised cash payouts.

Mishustin is now the most senior manager of Russia’s war effort (after Putin). He will be aided in this role by the excellent relations he built with the FSB and other security agencies during his 10-year tenure leading the Federal Tax Service. However, he is also known for advocating closer ties to the West. He held onto these ambitions even after he became prime minister, and reportedly, for example, aspired to put forward another Russian bid to join the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Even now, Mishustin is far from a hawk. This is in stark contrast to former Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, who has emerged as one of the loudest pro-war voices among Russian officials. Our sources suggest that, while Mishustin is certainly no liberal, he has never really supported this war.

Mishustin’s old friend, Moscow Mayor Sobyanin, was also likely kept in the dark about Putin’s plans to invade Ukraine. Neither Mishustin nor Sobyanin have an FSB background and neither knew Putin during the early years of his career in St. Petersburg. Before the war, Sobyanin was even praised in the Western media, which highlighted the mayor’s interest in modern, Western urban design. Since February, Sobyanin has fought to minimize the impact of the war on Moscow — for example, city authorities have tried to make sure that not too many pro-war “Z” symbols are visible on Moscow’s streets.

Putin’s overhaul of government means that civilian officials — like Sobyanin and Mishustin — will now be unable to take a backseat. As it turned out, it is these civilian officials, not the siloviki, as many assumed, who form the backbone of the regime. These career bureaucrats, ultimately the most competent part of the system, include many who were horrified by the invasion. Now, Putin wants them to take on prominent roles in the ongoing war effort.

Paradoxically, Putin’s security forces, in which he invested most of the country’s resources, proved unable to cope with the demands of the fighting.

In Putin’s new setup, Shoigu has been informally demoted. When the Crimean Bridge was attacked, he lost his position as a battlefield leader. Instead, Putin placed General Sergei Surovikin in charge of Russia’s forces in Ukraine. Now, even military logistics have been taken away from the Defense Ministry, leaving Shoigu as a rank-and-file member of Mishustin’s Coordination Council. Shoigu is only entrusted with menial tasks, such as calling his foreign counterparts to frighten them with tall tales of a Ukrainian “dirty bomb” plot.

This doesn’t mean that Putin is about to abandon his old comrade Shoigu. That’s not his style. After all, replacing a defense minister in wartime, especially one who polls as the country’s second most popular political figure, would be seen by Putin as an admission of mistakes. That is something the president always tries to avoid.

You can read more by Farida Rustamova and Maxim Tovkailo on their Substack.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.