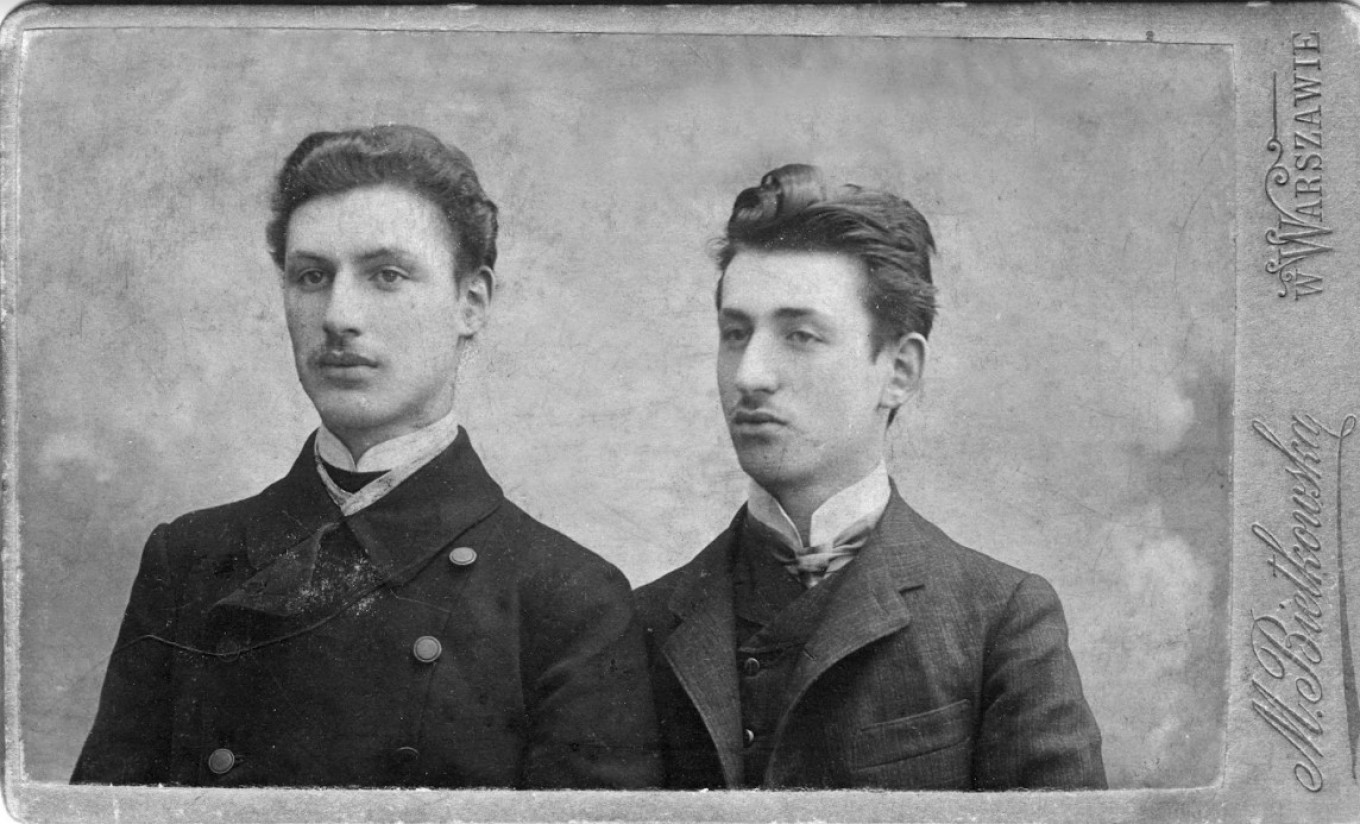

In late-19th century Warsaw, two brothers, Adolphe and Marcus Neyman, were born in a Jewish family. When they were young, their father went to America to find a better life, promising to come back for his wife and sons. He never returned, and so the two boys were raised by their mother, going to school, speaking a mix of languages – Polish, Yiddish, Russian – and earning money when they could.

When Adolphe was 21 and studying to be a pharmacist at the University of Warsaw, he married Marie, who came from a wealthy family. After some deliberation, the young couple moved to Switzerland, where he became the owner of a successful watchmaking factory. In 1906 they had a daughter, Eva and in 1913, her sister Eugenia (Genia).

Marcus stayed in Warsaw to take care of their mother. When war broke out in 1914, he joined the Russian army and fought so honorably he was awarded several medals for bravery. After his mother died and the Bolsheviks took power in Russia, Marcus moved to Moscow, determined to contribute to the creation of a new socialist society. He married Zina, a widow with two children, and together had a child, Anna, in 1923.

Like his brother Adolphe, Marcus was also a successful businessman during the NEP (New Economic Policy) period in Moscow. He and his family lived in a large apartment with a nanny for their children, and Zina contributed to the family budget with dressmaking. But soon the official policies changed, and "NEPmen" were stripped of their holdings and, in many cases, sent to prison or executed. Marcus was arrested and sent to Nizhni Novgorod to work in a factory. He returned to Moscow decades later, a broken man.

Many decades later, when Marcus’ granddaughter Elena learned the family history, “she would tell friends and acquaintances that one of the brothers was clever, and the other one – an idiot,” Ragozhina writes. “And that she was a descendant of the idiot.”

But as her daughter, Nadia, a senior journalist at BBC News based in London, would write as she uncovered the family histories lost over the decades, it was hard to say which branch of the family was fortunate and which was not.

After the families of Adolphe and Marcus stopped corresponding during the dark period of the Great Terror in the 1930s in the Soviet Union, the two families eventually completely lost touch. When the pendulum of history swung the other way at the end of the 20th century, Elena, her husband and daughter Nadia emigrated to London.

As a child, Nadia had been fascinated by the few family photographs that had survived the decades. As an adult in London, she began searching for her “Swiss cousins” on the internet. And finally, in 2010 two cousins, Russia Anna and Swiss Eugenia, met in Geneva.

“Worlds Apart” is the story of the extended Neyman – later changed to Neuman – family. To tell this complex story of disparate lives separated by languages, generations, and history, Ragozhina is narrator, interviewer, historian and, in the end, a character in the story. She is a historian setting a scene in time and place or a novelist telling a harrowing story of the family’s escape — or sometimes a failure to escape — the demonic forces of 20th century Europe. She tells not only about the grand events and unspeakable tragedies in the lives of her relatives, but about their squabbles, love affairs, happy and unhappy marriages. By the end the readers know them so well, they are happy that Genia finally finds her soulmate at the end of her life. Sometimes Ragozhina steps aside and lets a member of the family describe an event from the perspective of today, or she quotes from diaries and letters.

And sometimes she is not the storyteller, but a story-maker — the member of this remarkable family who brought them back together.

Worlds Apart: The Journeys of My Jewish Family in Twentieth-Century Europe

In May 1940, Eva, the daughter of Adolphe and Marie Neuman, her husband Stanislav Zousman (Stanis), their daughter Anita and Stanis’ brother and family decide to go to the Belgium seaside resort of De Panne. “The name of De Panne doesn’t immediately bring up the horrors of the Second World War,” Rogozhina writes, “since in the British collective memory it has been overshadowed by the events that unfolded in the town’s southern neighbour – the French resort of Dunkirk, some twenty kilometres away.” When war breaks out and the low countries are overrun by the German armies, the families try to make their way to France, leaving almost all of the possessions behind — except for a fox stole Eva kept with her, which would play a role in their survival.

From Chapter 11: A Holiday in De Panne

By 21 May British, French and Belgian troops were effectively trapped along the French coast. A French division had been successful in holding the Germans by the city of Lille and giving the Allies time to gather in Dunkirk, but now their time was running out. British prime minister Winston Churchill’s call for all small private boats and ships to gather along the coast to help the evacuation process sounded like a crazy dream.

Stanis and his family didn’t wait around for the evacuation. They joined other civilians fleeing the bombs and the explosions. They were now heading southeast, hoping to find a train that would take them further away from the fighting, the smoke that had penetrated their clothes and the terrifying screams of the people witnessing the disaster unfold in front of their eyes.

Stanis and Eva didn’t realise that they were entangled in the middle of one of the biggest Allied evacuation operations of modern warfare. Operation Dynamo, later also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, would continue for almost ten days, during which the local population and everyone who found themselves in the area would experience war at first hand. More than 20,000 civilians would lose their lives in France in May and June 1940.

The family continued walking. They were now joined by thousands of people. Bikes, carts, horse-drawn carriages, trucks, pushchairs and prams, young and old, women and children, people were walking away from the fighting and towards central France. They carried their bags on their shoulders. The horses were laden with food and necessities, and many brought their cattle with them. Along the roadside, people stopped to give the elderly and the young a chance to rest and to catch their breath. Nobody knew how long the journey would last. No one could predict where they would spend the night. The locals knew the area and they found the shortcuts. Everyone else followed. They crossed the fields and went past abandoned farmhouses. Many had been burnt to the ground; others were still blazing. The refugees – and that’s what these people had become overnight, having been forced to abandon their homes – were a wave of human suffering. Many would die along the road. Some would reach their destination. Few would ever speak of the traumatic experience. Many would choose to forget.

Anita remembers the warmth of her mother’s fur stole. She slept on it and covered herself with it when it got cold at night. It became more of a treasure than Eva could have ever imagined when she first bought it the previous winter in Geneva.

Anita also remembers the shoes she wore. Her Scottish slippers, as she called them because they were made of velvet, with a black top and a small button loop and a button. For many days she looked down at her feet and saw those slippers. They were not proper footwear and were not meant to be worn outside, but the niceties of her middle-class upbringing had gone out of the window many days ago. Anita’s slippers looked out of place amid the burnt-out fields and all the people fleeing. Her legs were hurting, and she was hungry.

When an opportunity presented itself, Stanis bought a motorcycle with a sidecar. A young man was found to drive it. Stanis insisted that his wife and daughter should continue the journey with the driver. He would look after his father and his brother’s family, and they would find another means of transport and follow Eva as soon as they could. Their destination was Lyon. They were far away; the road could take several days, but Eva and her husband agreed to meet at the hotel nearest to the train station. They were sure that they would be reunited in a few days.

As Anita recalls, ‘My mother and I found ourselves with a man who was happy to drive the bike with us in the sidecar. And like that we drove. We drove along the roads congested with all the people fleeing. We found ourselves among this river of people, with little carts that they were pulling, kids’ prams, where they had put food or mattresses, or in cars, if they had them. It was awful. And we were among these people, trying to get further into France, escaping the encirclement by the Germans.’

Once the petrol ran out, they parted ways with the driver and abandoned the motorcycle and the sidecar. They had been able to advance further into France, but the flow of refugees prevented them from going fast. Once again, Eva and her daughter started walking. The summer of 1940 was warm and dry, which no doubt saved the lives of many of those who were trying to escape the fighting.

Even now, Anita remembers the hunger. They went with little or nothing to eat for days, sometimes buying bread and vegetables from the locals they came across on their journey. It had been weeks since they’d had a full meal, as Eva would be reminded one day.

I will never forget a farmer who gave me an egg for Anita and a lady who wanted to snatch it from me to give it to her elderly husband. I kept it for Anita, I was able to boil it, she ate it very happily and she vomited it straight away.

Finding shelter for the night became one of the main priorities. People were sleeping under trees and in the bushes, but Eva hoped for a safer place to escape the occasional chill of the night breeze and the dew of the morning grass. The duvet and her fur stole still provided them with shelter, but it was warmer and drier inside. When they came across a farm that was still inhabited, Eva was hoping for some food, as well as a place to sleep. When she knocked on the door, she was expecting some sympathy – a young mother with a child was easier to accommodate than a family of eight, and she had been lucky in her previous attempts to find shelter. She was turned away. The owners were afraid of the numbers of refugees arriving on their doorstep. Their state of fear and uncertainty forced them to turn away people who had been walking across their lands for days.

Fate saved Eva again. As she took cover in the nearby fields at night, she was awoken by Stuka planes, their howling sounds warning of an imminent attack. In horror, Eva watched the German aircraft dive as it approached its target, machine-gun bullets spraying everything in their wake. A bomb was dropped and the farm went up in flames. Eva and Anita ran as far as they could to escape the heat of the flames and the danger that the fire would spread to the dry fields nearby.

A common sight over the French beaches and surrounding areas, Stuka planes terrified the people. The sirens would forever be engraved in the memories and nightmares of those who survived the war. They left chaos and destruction that was equally difficult to forget. The bodies of those who were not quick enough to hide. Those who ran in the wrong direction, or those who were simply too close to the target of the Nazi fighting machines – the terrifying sight of war that was witnessed by women and children trying to run for their lives.

Eva threw herself on the ground, or in a ditch, trying to cover Anita with her own body. What would happen to her child if she died, she thought? She would have died too. She was too young to understand what was happening, too young to realise where they were. It would be better if they died together.

Eva was surprised when one day they approached a German checkpoint. Along the way she had come across French soldiers who often shouted to them that the Germans were coming, but no one understood that they meant to say that the Germans had surrounded the area. Eva was convinced that they had been walking away from them all this time, but in fact the German troops were also ahead of them.

Eva could barely see the checkpoint, for all the people who were attempting to get through. Long lines of trucks, carriages and those on foot were patiently waiting for their turn. They were hoping to cross into occupied France. Eva had been clinging onto a shred of hope that there would be a chance to go to Switzerland, but it soon became clear that Belgium was her only option. She came face to face with the first Nazi soldier she had ever seen. She didn’t know how to voice her request. She didn’t know how to behave with this man, the occupier, the man who was fighting for Hitler. But she was in a desperate situation. She could speak German, and she had to use all that was in her power to get herself and her daughter out of these French fields that had been their home for the past six weeks and back to the Belgian capital.

It was Anita who eventually came to her mother’s rescue and saved the day. ‘It was the time of daisies,’ she tells me. ‘There were lots of them, in the fields, everywhere. Long daisies and poppies, very fragile wild flowers. They were almost as tall as me. I hurried over to my mother and the officer, and handed him a bunch of flowers, telling him that they were for him! So he took me in his arms with the flowers, and told my mother that he had a daughter my age at home. He would have probably got a photo out. He asked us where we came from and what he could do to help. When mother said Switzerland, he laughed.’

There were no open roads into neutral Switzerland, but he could help get them to Brussels. The officer took a liking to Eva and her daughter, and he offered them his driver, who would take them to the Belgian capital. To the envious stares of everyone else in the queue, Eva and Anita got into the chauffeur-driven car, their nightmare almost over.

Eva was relieved. In the last six weeks she had walked more than she had ever done in her life. Her legs were now stronger, but the exhaustion was making itself known. In the hours it took to get to Brussels, Eva came face to face with devastating reality. There were German troops everywhere, Nazi flags flying on many buildings. People seemed to be getting on with their lives, but the air was thick with tension. Eva noticed the forced politeness, the cautiousness when a German patrol was spotted in the area. As she got out of the car and thanked the driver, she was aware of the curious looks in her direction. A tired, dirty, unwashed woman with a little girl, who had both seen better days, got out of the car in front of the Hotel Le Palace – one of the most luxurious in the city. The porter wasn’t sure whether to open the door for the strange pair or to chase them away, but Eva’s demeanour told him to hold back.

Inside, in the mirrors of the expensive décor, Eva gave herself a curious look similar to those of the passers-by outside. She glanced at the ragged woman and for a second didn’t realise that she was looking at her own reflection.

Eva asked for the biggest room with the biggest bathroom, and after taking five or six baths she was finally happy to go to bed. However, sleep eluded her. Having spent so many nights lying on the ground or in haystacks in the middle of French fields, she couldn’t settle in the luxury of the expensive hotel bed and ended up finding more comfort on the floor.

Excerpted from “Worlds Apart: The Journeys of My Jewish Family in Twentieth-Century Europe,” by Nadia Ragozhina, published by SilverWood Books. Copyright © 2020 Nadia Ragozhina. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Footnotes have been removed for ease of reading. For more information about the book and author, see the site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.