Artist and activist Daria Apakhonchich was one of the first people in Russia to be labeled a “foreign agent,” a status that forced her into exile and allowed her to turn routine government paperwork into a form of protest art.

Now based in Europe, Apakhonchich’s creative reports to the Justice Ministry — filled with anti-war drawings and personal reflections instead of bureaucratic language — chronicle both the absurdity and brutality of Russia’s “foreign agents” law. These reports will be shown at Artists Against the Kremlin, an upcoming exhibition co-organized by The Moscow Times in Amsterdam.

She spoke to The Moscow Times about transforming bureaucracy into resistance and finding language for grief.

The Moscow Times: Your quarterly reports to the Justice Ministry that all ‘foreign agents’ are required to submit are supposed to list all your expenses and income, but you draw and write messages to the ministry instead. How did that idea come to you?

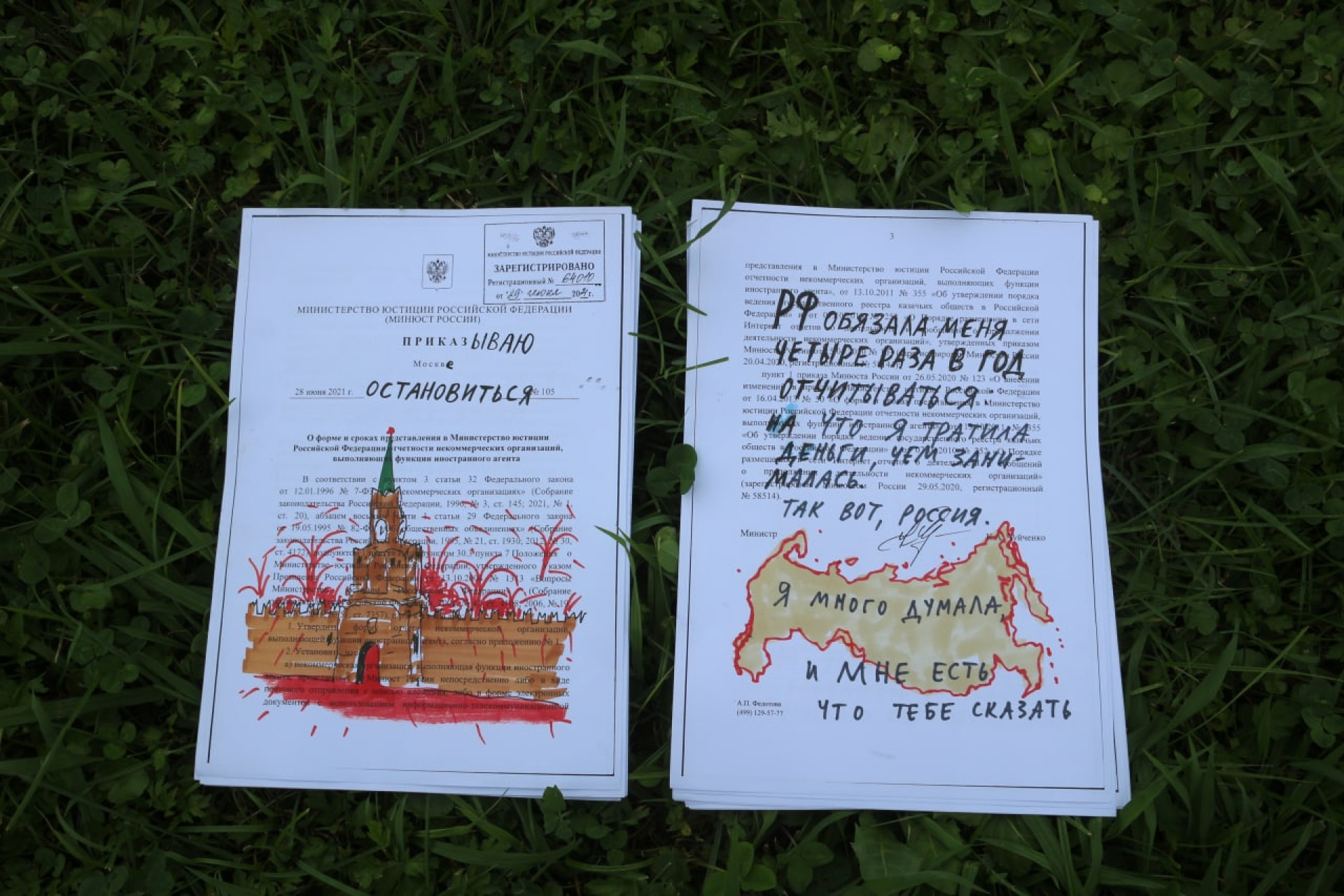

Daria Apakhonchich: I wanted to make unusual, kind of funny reports to the Justice Ministry from the very beginning. The first time I had to submit one was in the winter of 2021. Back then, it was still unclear where this was all heading.

At the time, I was outraged — first, by the fact that I had been labeled a foreign agent, and also that I had absolutely no idea how to fill out the reports. It’s a unified document that both individuals and organizations are supposed to fill out. Some of the questions are really hard to answer if you’re just a person, not a media outlet or an NGO. That outraged me from a logical standpoint. To be a foreign agent, you’re expected to have certain competencies, and those don’t just magically appear the moment they assign you this status. Does that mean I should be fined or even put in jail because I can’t figure out how to fill out the form?

That first time, I wanted to express those feelings like this: I wanted to put on bright lipstick and kiss every single page of the report, over and over again — to make it into an art object. I imagined sending all the pages covered in red lipstick kisses to the Justice Ministry. A lawyer advised me to get a visa first, just in case I’d need to leave Russia, so I put that plan on hold. Even when I left the country in 2021, I still hoped I’d be able to return, so I tried to fill out the reports correctly. I did that for a year until the full-scale invasion began. After that, staying silent was no longer an option. I wanted to speak out about all of it — especially since I had the one real privilege of being outside prison.

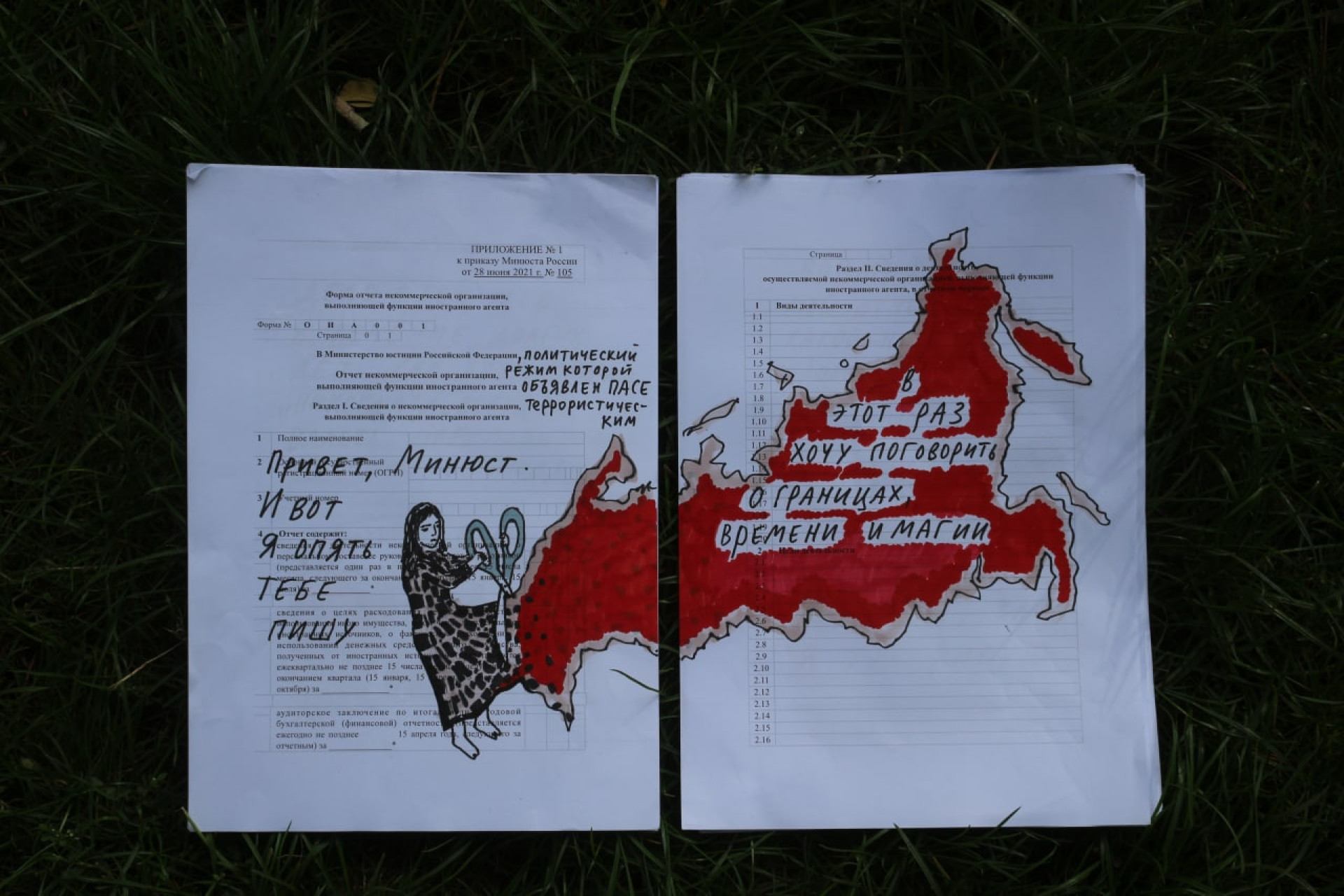

I wrote a lot on social media, and I’d talk about the war in interviews. I just couldn’t keep adding that phrase every time [foreign agents are required to add a lengthy disclaimer to all public statements and posts, including on social media]. Because you’re talking about a horrific crime, about genocide, yet you’re doing it while complying with the rules of that same monstrous regime. Like: ‘Yes, let’s talk about genocide — but first, let me remind you of the foreign agent law.’ At some point I realized: that’s it. That’s a line I just can’t cross.

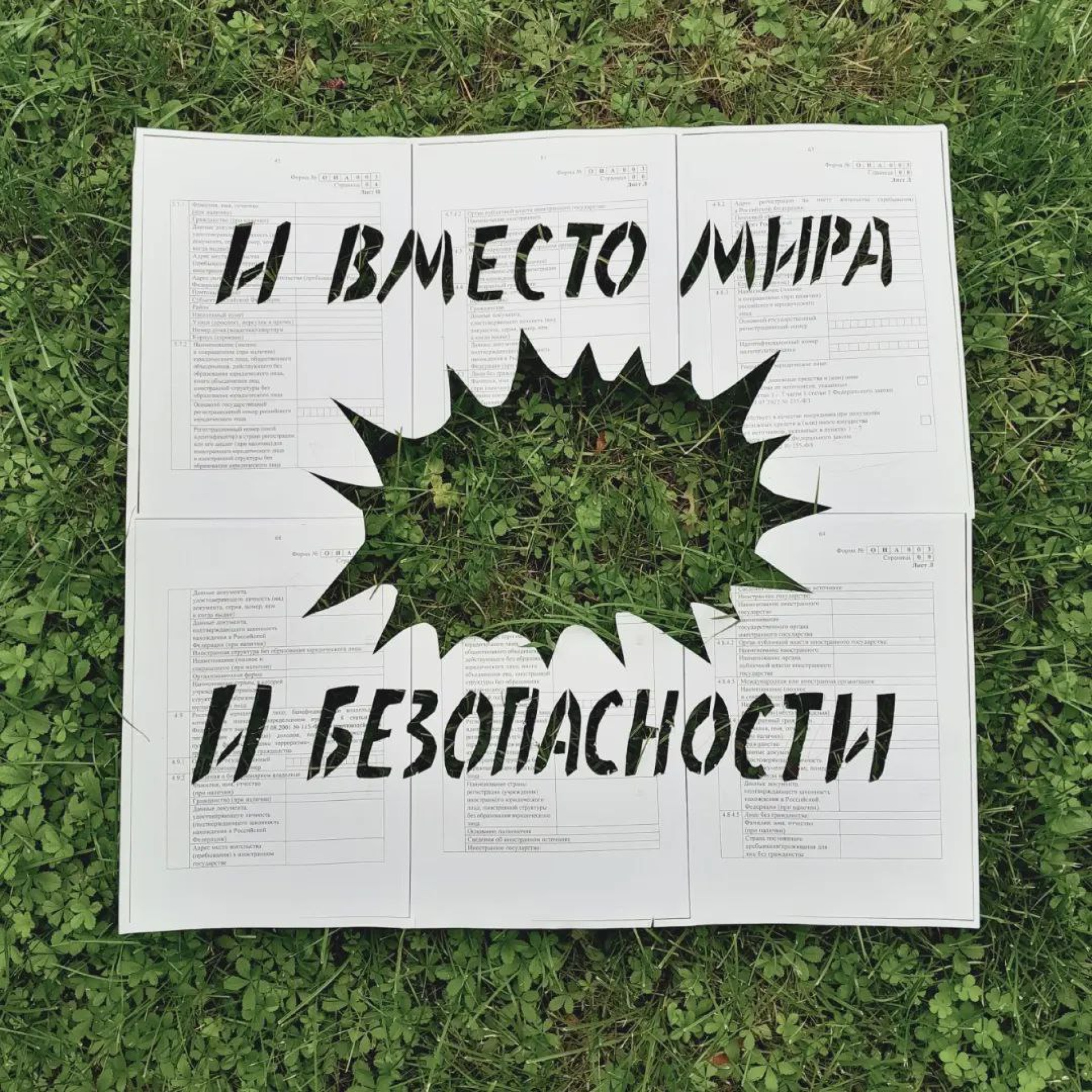

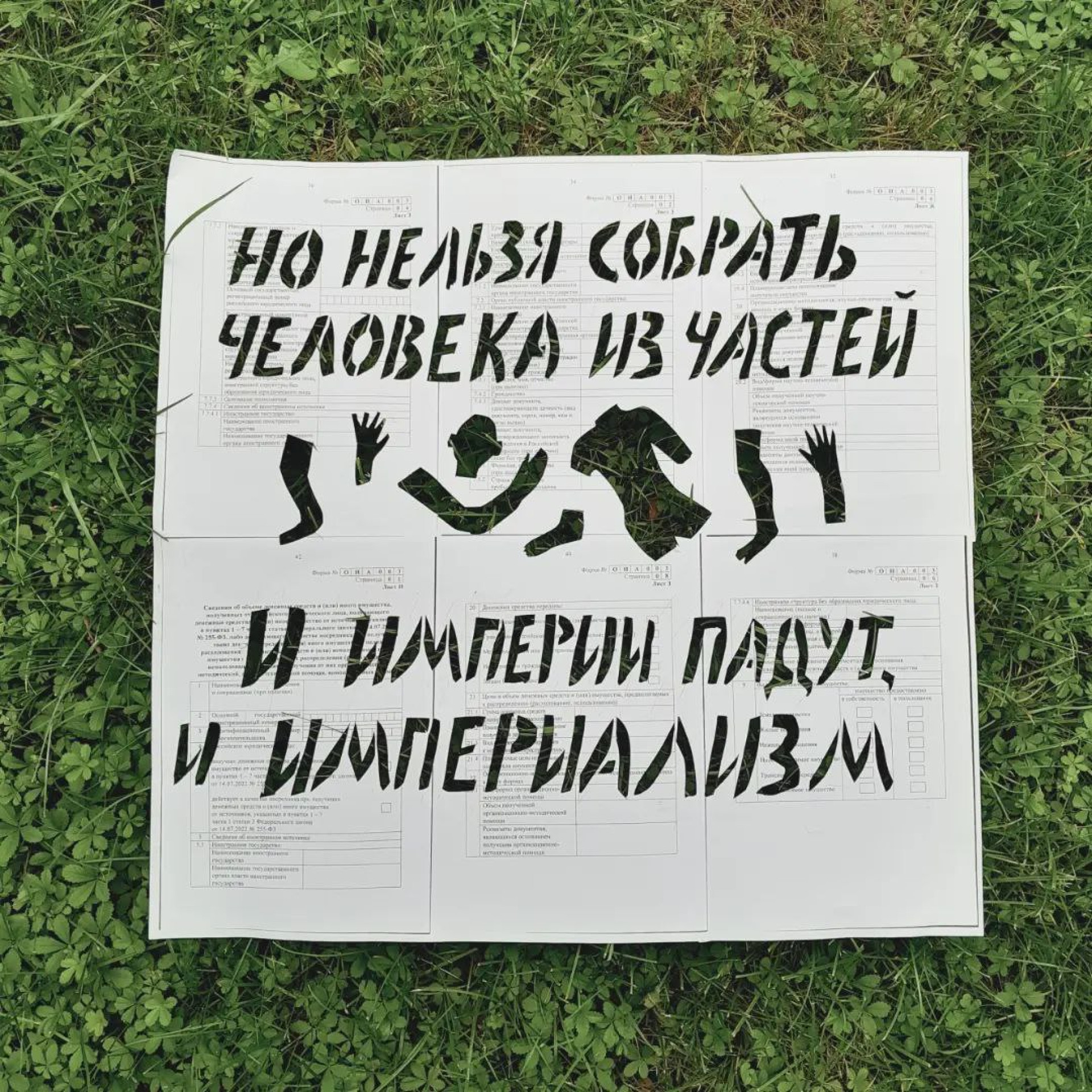

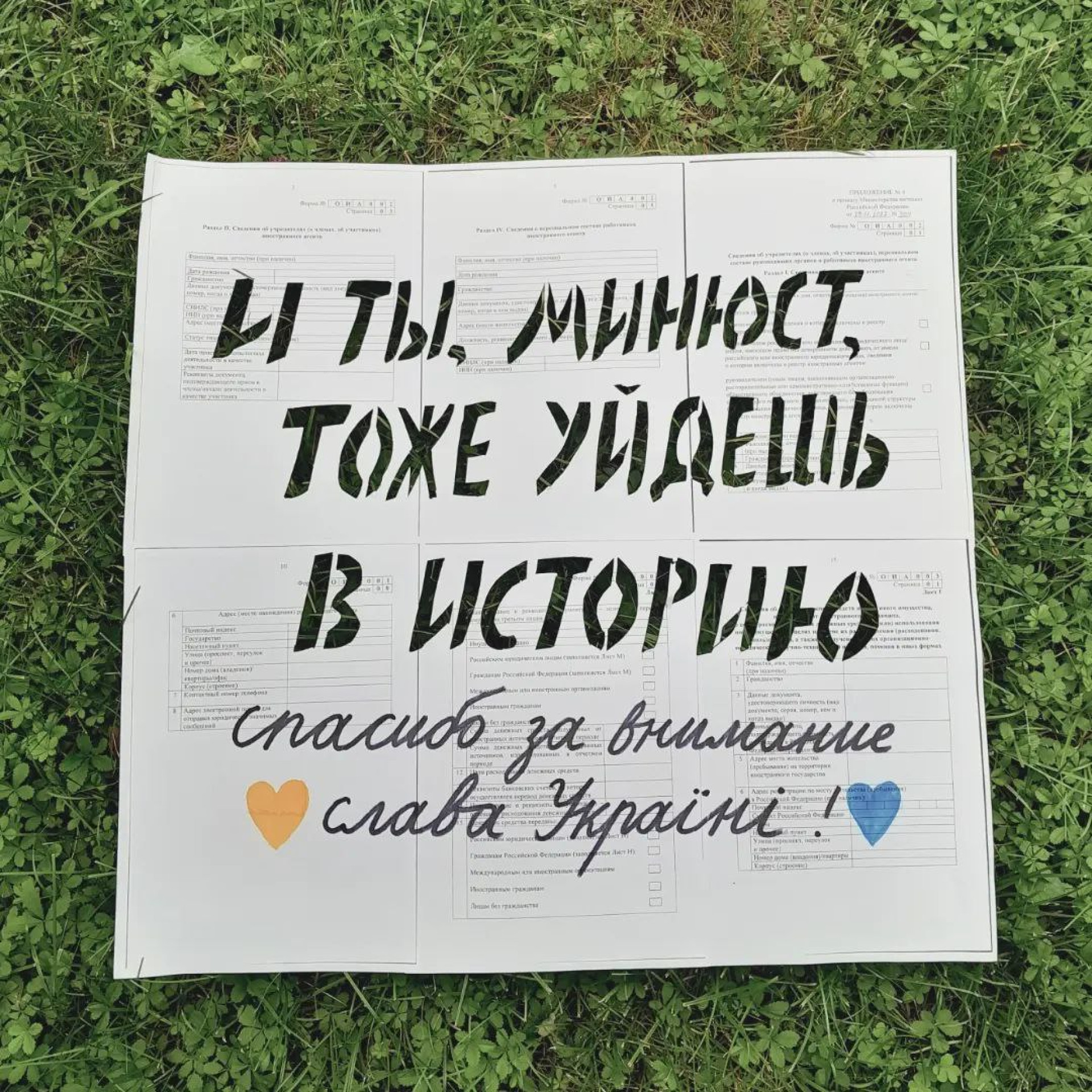

My first artistic report was an anti-war manifesto. I drew little crosses to mark how many children had died in the first days of each month of the war. I repeated the same idea three months later — because the war was still going and I still needed to talk about it. After that, it became a kind of tradition.

Usually I don’t sit down and work out a concept in advance. I just sit with the sheets, look at them and think: what felt important to me over these past three months? It’s always about the war, but sometimes it’s more about the state’s hypocrisy during the war. Other times, it’s about the opportunities we’ve lost because of it. Sometimes it’s about my own personal feelings.

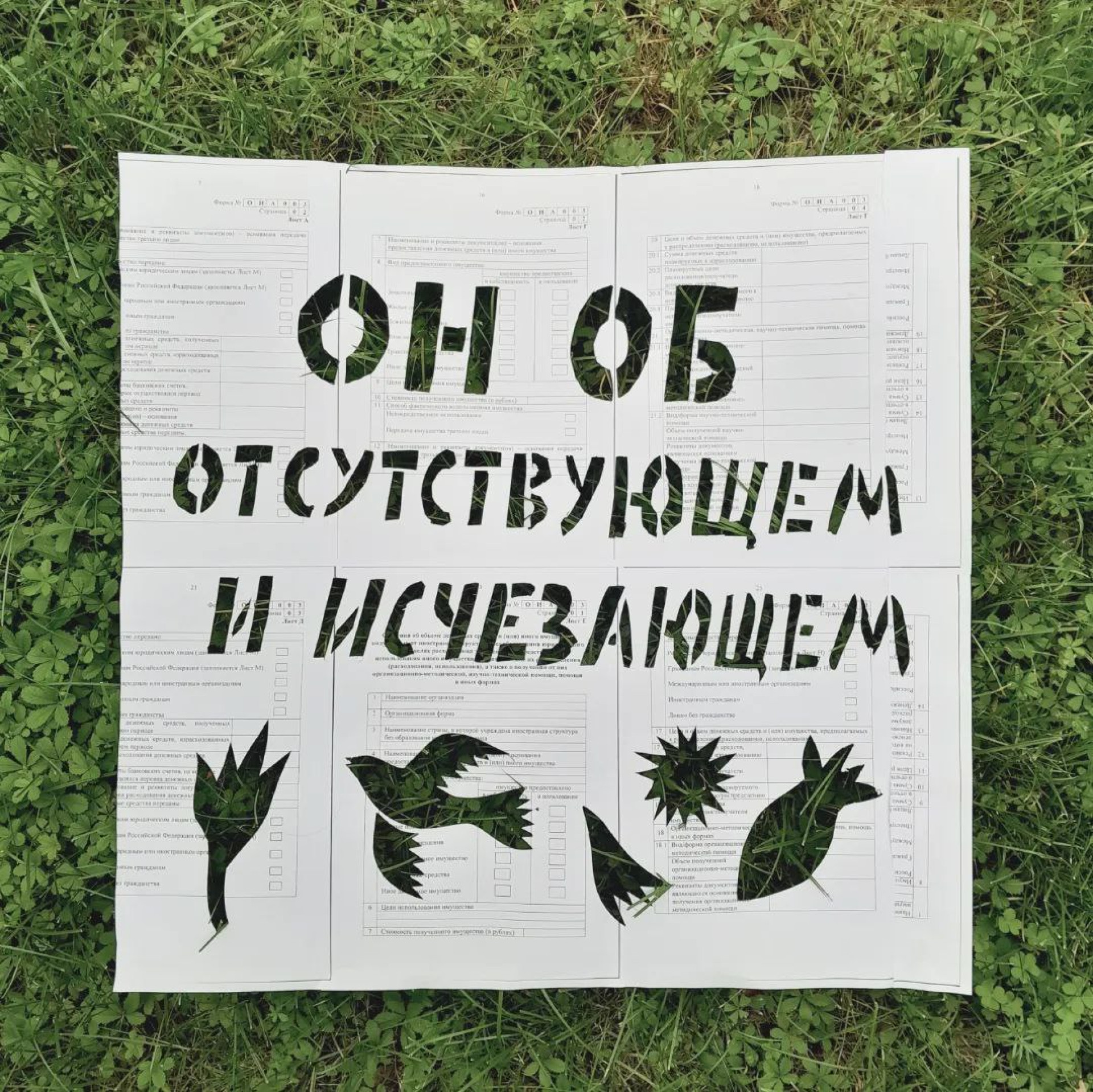

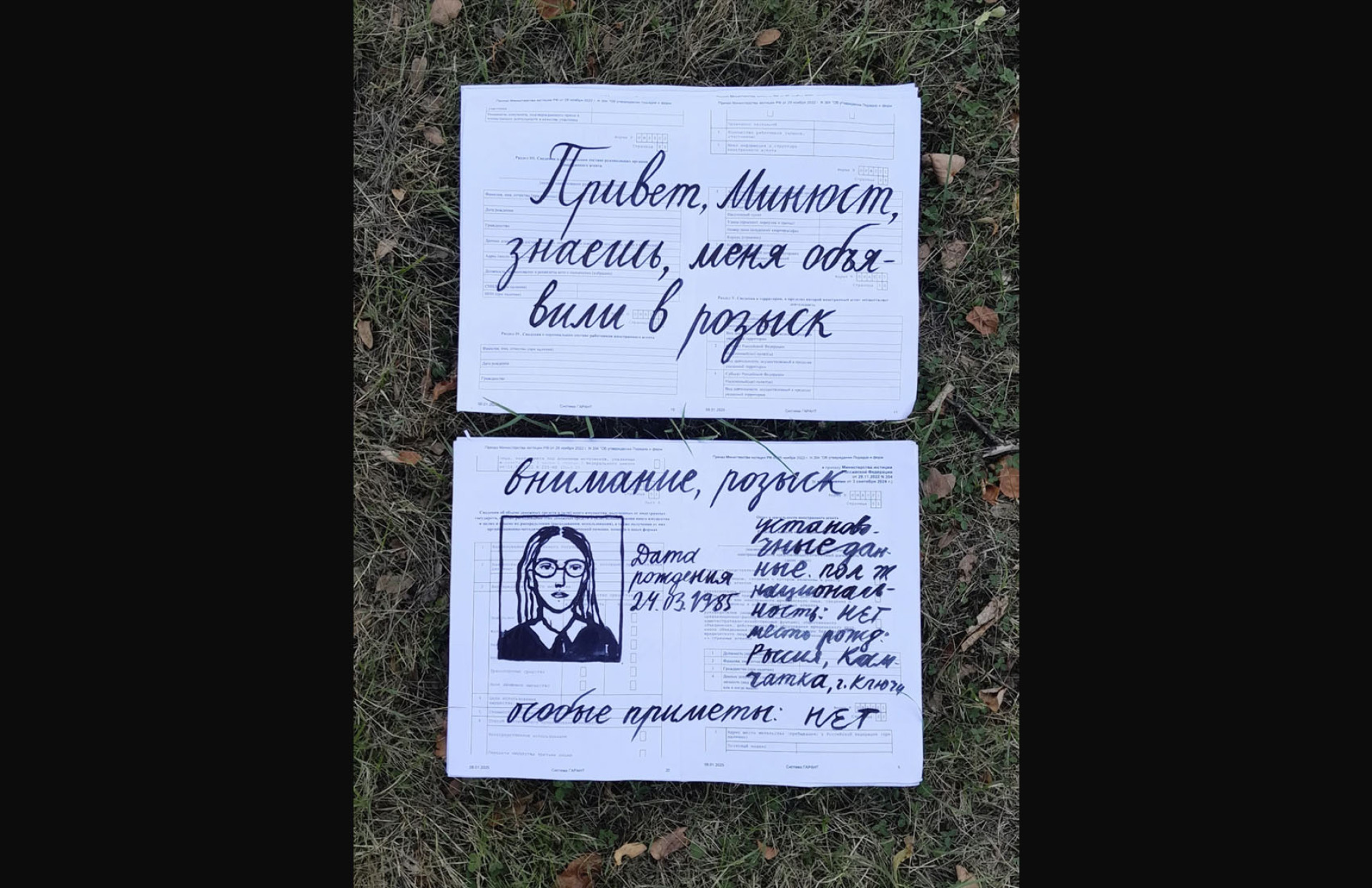

Right before your latest report, you were declared wanted by the Russian authorities…

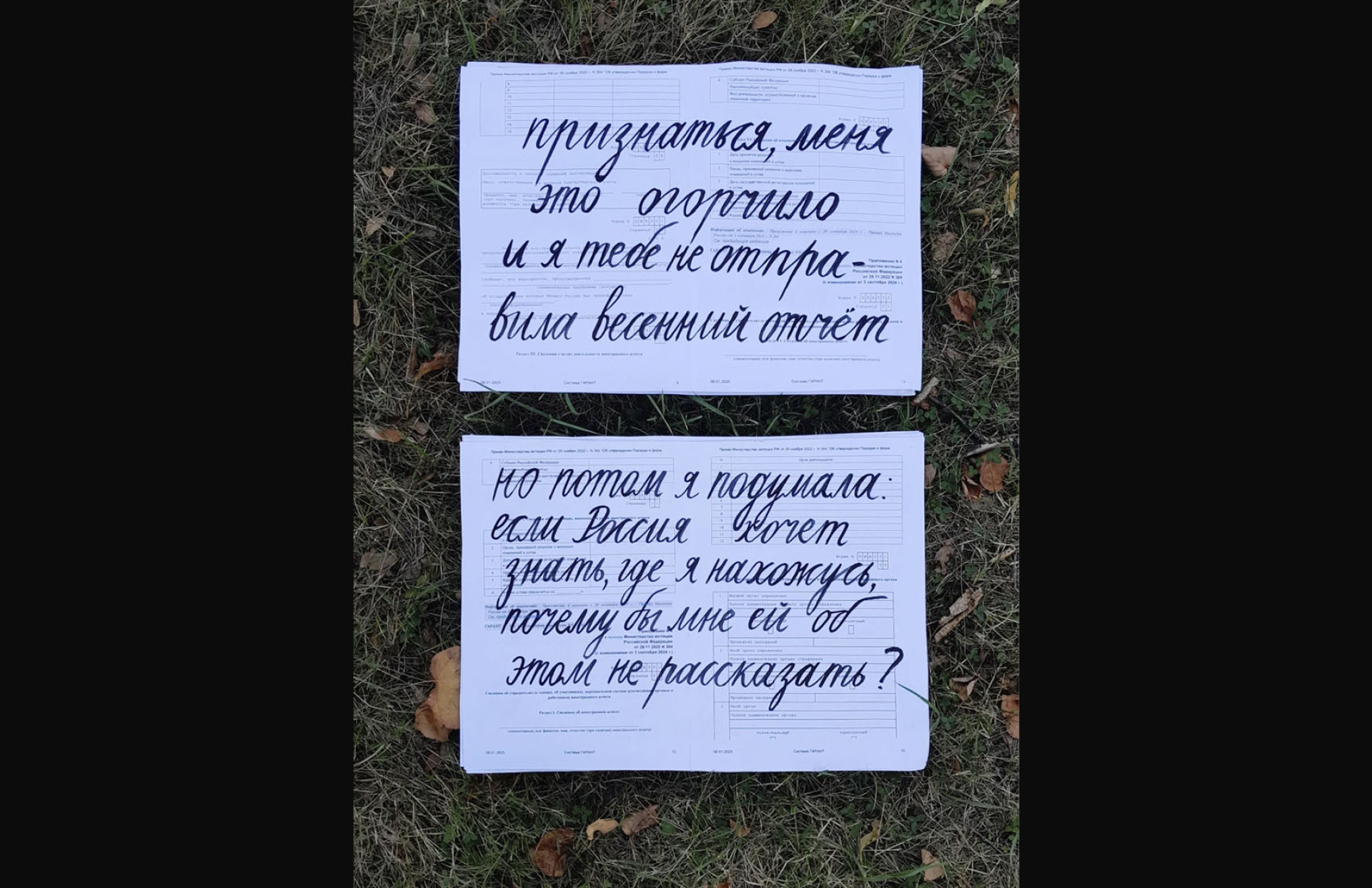

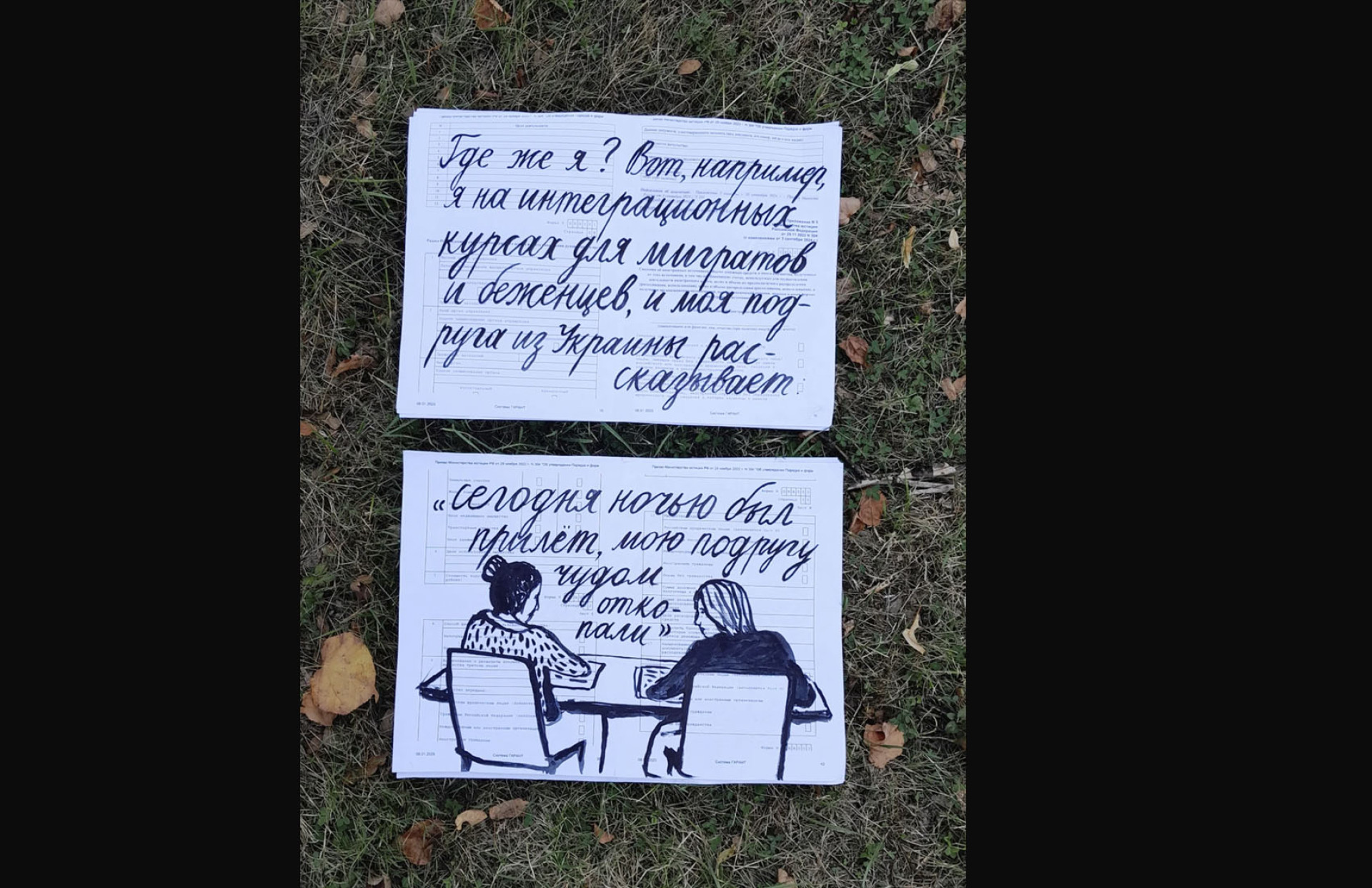

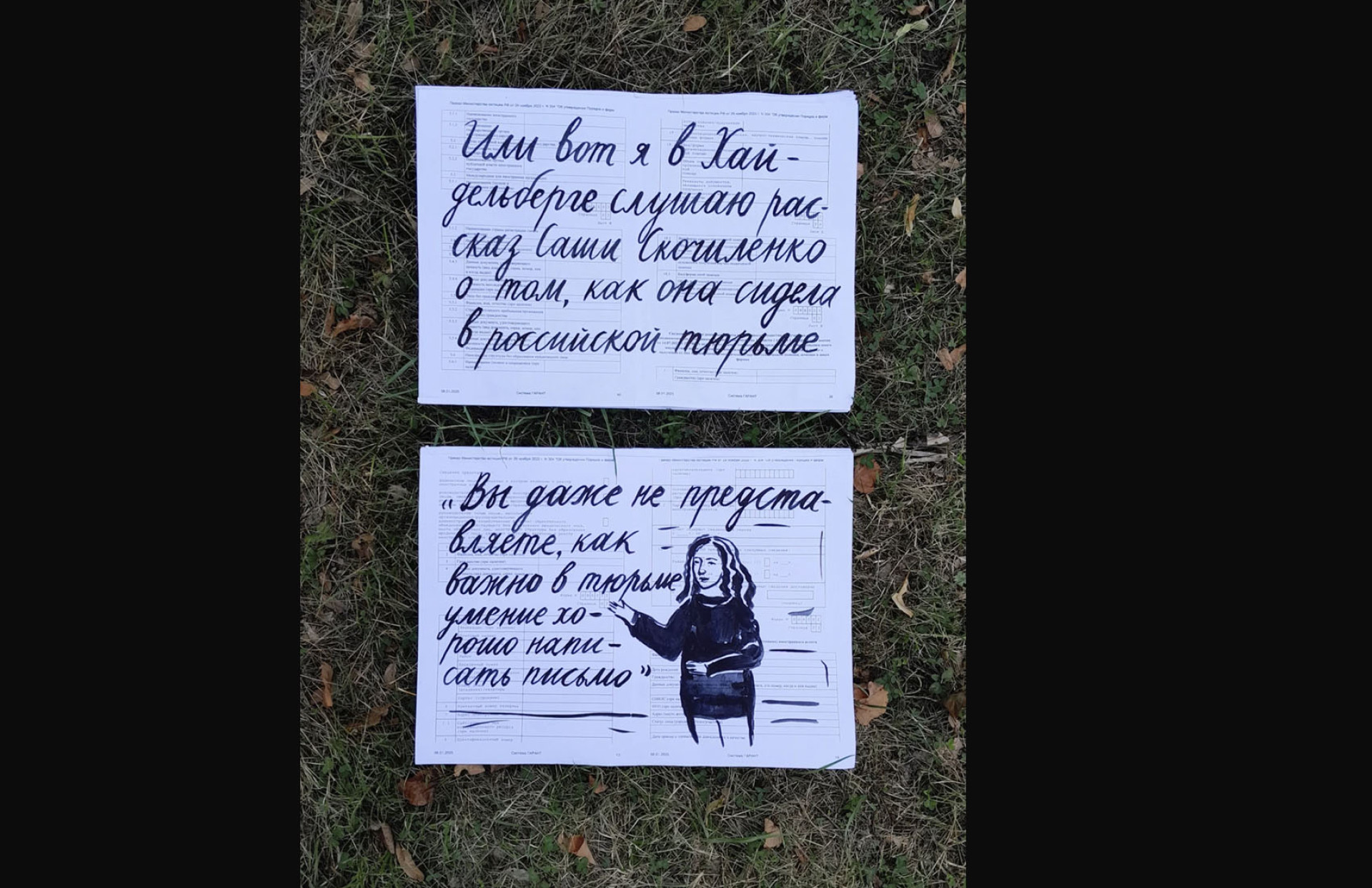

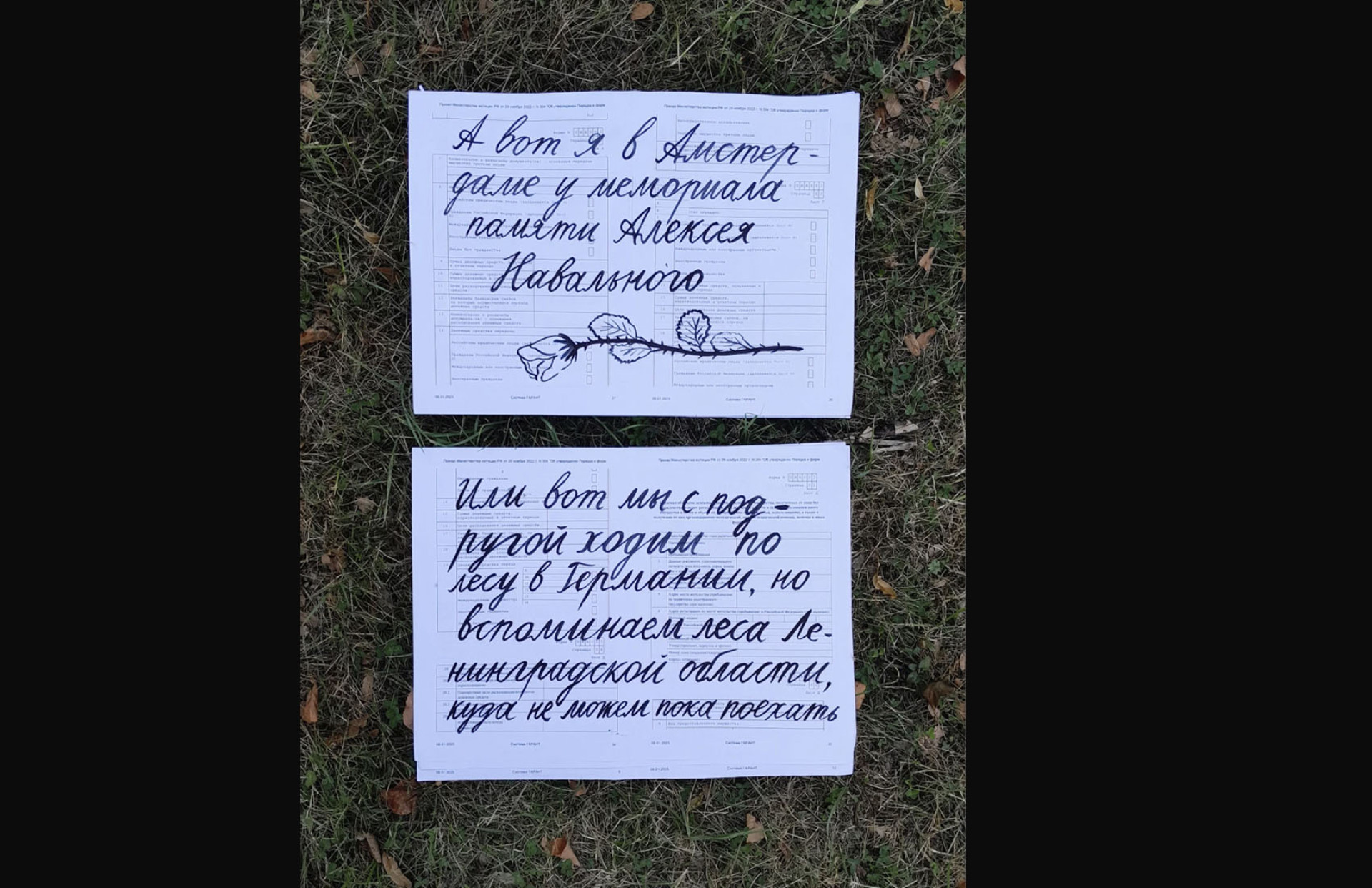

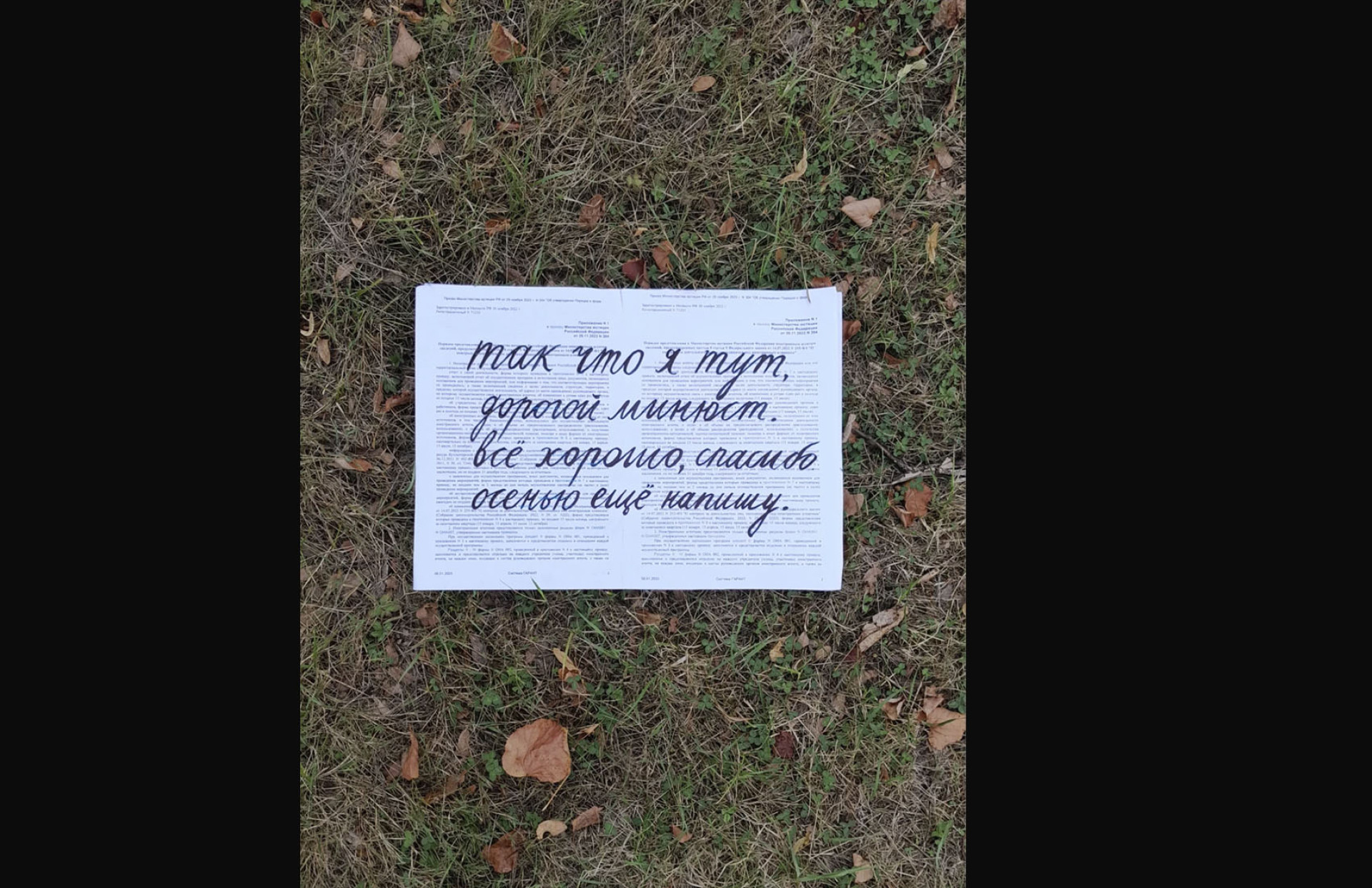

My last report was about exactly that. I thought: ‘If they’re so curious about where I am, I’ll tell them.’ I drew several images — like me and a friend walking through the woods in the Netherlands. Or sitting in an integration class in Germany, learning German. There are a lot of Ukrainians in my class, and they talk about the war. They tell us about the explosions, the destroyed homes, the ruined lives, the trauma their loved ones are dealing with. It’s an honest answer to the question: ‘Where am I?’

It’s like you’re writing letters to someone, and he never replies.

I’ve been doing more and more literary work in recent years, and I understand that these reports give me an opportunity to write short stories. Gradually, a kind of sincerity appears, a feeling like I’m writing love letters to someone who doesn’t love me. There’s some kind of drama that connects us, and for some reason, there’s this need to keep writing these letters. But all the feelings are very traumatic.

Have you ever gotten any signals or reactions from the Justice Ministry?

The fact that they put me on the wanted list is a signal, but there was another one before that. I was living in Tbilisi then, before the war started, and every time I sat down to write that report… You’re supposed to explain in detail where you get your money from. That annoyed me, because I already paid taxes as a Russian citizen. What more information did they need? Of course, I didn’t want to write the names of the people who supported me financially, so I wrote: ‘I get my money for living from my lovers, male and female, whose names I will not give you, because that’s personal information, an invasion of privacy.’ That was the only time they replied to me. They sent me an email that said, ‘The report was submitted in the wrong format.’

If we continue the metaphor of love letters, it’s like you wrote a letter to your beloved, and he corrected your mistakes.

Yeah. You say: ‘I love you,’ and he replies: ‘Why is there a space before the comma?’ The response is not about the content, but the form.

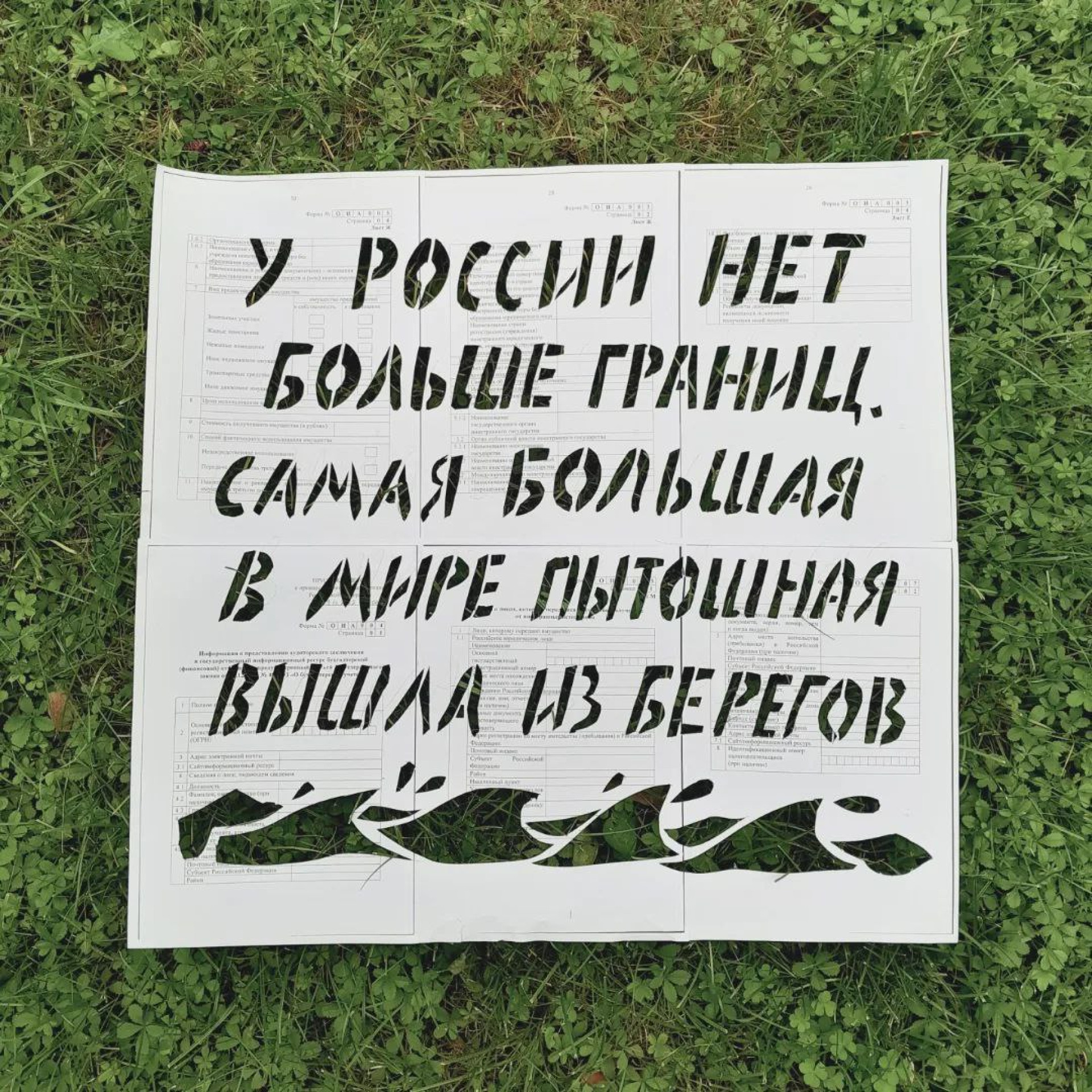

It’s also important to remind myself what this is all about. Because the whole thing is objectively funny, but it’s not funny at all that I’m on the wanted list. I’m a teacher, I’m a writer. I’ve never killed anyone, I haven’t committed any crimes that would warrant depriving me of freedom. I’m not dangerous. My crime was that I dared to fill out the reports the wrong way, and they seriously want to put me in prison for that.

One time a friend said: ‘Send them a photo of yourself in Monaco with a wad of cash, smoking a cigarette in a long holder.’ I saw that there was indeed an element of grotesque humor in that. But that’s not the main thing. The main thing is that what our Justice Ministry is doing is a horrific crime against common sense, against humanity, against the law. It’s important to keep reminding people of that.

So for you, this is a communication with the Justice Ministry specifically, not with the audience who will look at your report at the exhibition?

I started making art because I had no other way to talk to the state. We were involved in activism and I had taken part in election monitoring since I was 18. But it wasn’t enough, and art became a way to speak louder. Now that I’m a foreign agent, it’s almost the only way. We don’t have any other channels of communication left with this state.

Continuing this stupid metaphor of a traumatic love correspondence, it’s one of those situations where you’re in some kind of abusive relationship. The presence of an observer who can witness the communication failure and say: ‘Yes, you said that’ and ‘Yes, they didn’t respond to you’ — that in itself is therapeutic.

The Europeans who see your work are that observer?

Yes, because my case is political, and politics happens in public. This publicity and the chance to speak with witnesses — that’s exactly what our state doesn’t like and what it avoids. The foreign agent law is about that, too. It’s about not sharing information, about making it dangerous to speak with dissenters. They want us, the foreign agents, to be isolated. For people to avoid us like we’re contagious, to be afraid to work with us.

Events like exhibitions or online publications let us say: ‘Look, we exist, we want something different and we’re not afraid to speak about it’ — and we’re paying a high price for that right.

The audience for Russian artists is essentially made up of outside observers — as you said, witnesses — since many people in Russia won’t see these works.

Yes, and that’s even true for artists who haven’t emigrated. Inside Russia, talking about what the state is doing wrong is almost impossible — it’s dangerous. People are jailed for anything. Like [Russian writer Viktor] Shklovsky said: ‘When we give way to the tram, it’s not out of politeness.’ People who are now forced into silence in Russia, or have to speak anonymously, are not doing it out of politeness.

The fact that we left didn’t make us different people. It didn’t change our values or our meaning. We’re just not physically there. I’m sure so much has changed in the past four years, more than in the last few decades, but it’s still my country, and I’m still in a complicated, dysfunctional relationship with it.

Do you think about returning to Russia?

I think that being able to live in a country where you speak the language and do creative work, where your audience is, where you grew up and went through important stages of becoming — that’s an incredible value, and it’s something you don’t realize until it’s gone.

On the other hand, the ability to say what you think and not stay silent when you see repression is essential. Of course, it would be great to return to Russia if it were free and safe, if it were a country where you want to create and where no one puts you in prison for wanting to fix something. But we don’t have a say in this.

Who else among your fellow artists at the Artists Against the Kremlin exhibition have you been impressed by?

Sasha Skochilenko, my favorite contemporary artist and political prisoner, luckily a former one. Of course, it’s an honor to participate in an exhibition like this. There are many amazing artists there. But Sasha’s work is especially important to me because it’s a female view on prison, on activism. And Sasha is an incredibly brave and honest person.

Daria Apakhonchich's art will be displayed at the second edition of Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition organized by The Moscow Times and All Rights Reversed gallery at De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 15-Sept. 4.

Visit the exhibition website for more information.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.