Baroque enthusiasts and lovers of bygone scandal will welcome the news that Moscow’s Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts is hosting an unprecedented exhibition of the early 17th-century master Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

The three-month exhibition is the culmination of the Italian-Russian year of cultural exchange and the most comprehensive display of Caravaggio ever held abroad, featuring 11 works spanning his eventful artistic career.

The difficulty of organizing such a show — each work belongs to a different Italian museum, necessitating a string of separate contract negotiations — and Caravaggio’s critical contribution to modern painting make this a significant event in Moscow’s arts calendar.

Caravaggio “fundamentally altered the direction of art in a similar way to Michelangelo, Rafael, Titian and Leonardo da Vinci at the start of the 15th century. And he did this alone,” museum director Irina Antonova told the Vesti news channel.

Largely overlooked for centuries by critics blinded by the leading lights of the Italian Renaissance that preceded him, Caravaggio was only rediscovered in the 1930s and championed as a true great of European art. His status has since grown to such an extent that he is now viewed as “the first modern painter,” responsible for influencing Rembrandt and Velazquez and laying the foundations for many techniques used in modern photography, including cropping and one-source light.

Caravaggio’s biography is as memorable as his artwork. Over his short yet intense life, he had a number of brushes with the law and gained a reputation for carousing, brawling and holding public flings with members of both sex. His dissolute lifestyle eventually caught up with him, however, and he was forced to flee Rome after killing a man over a game of sport.

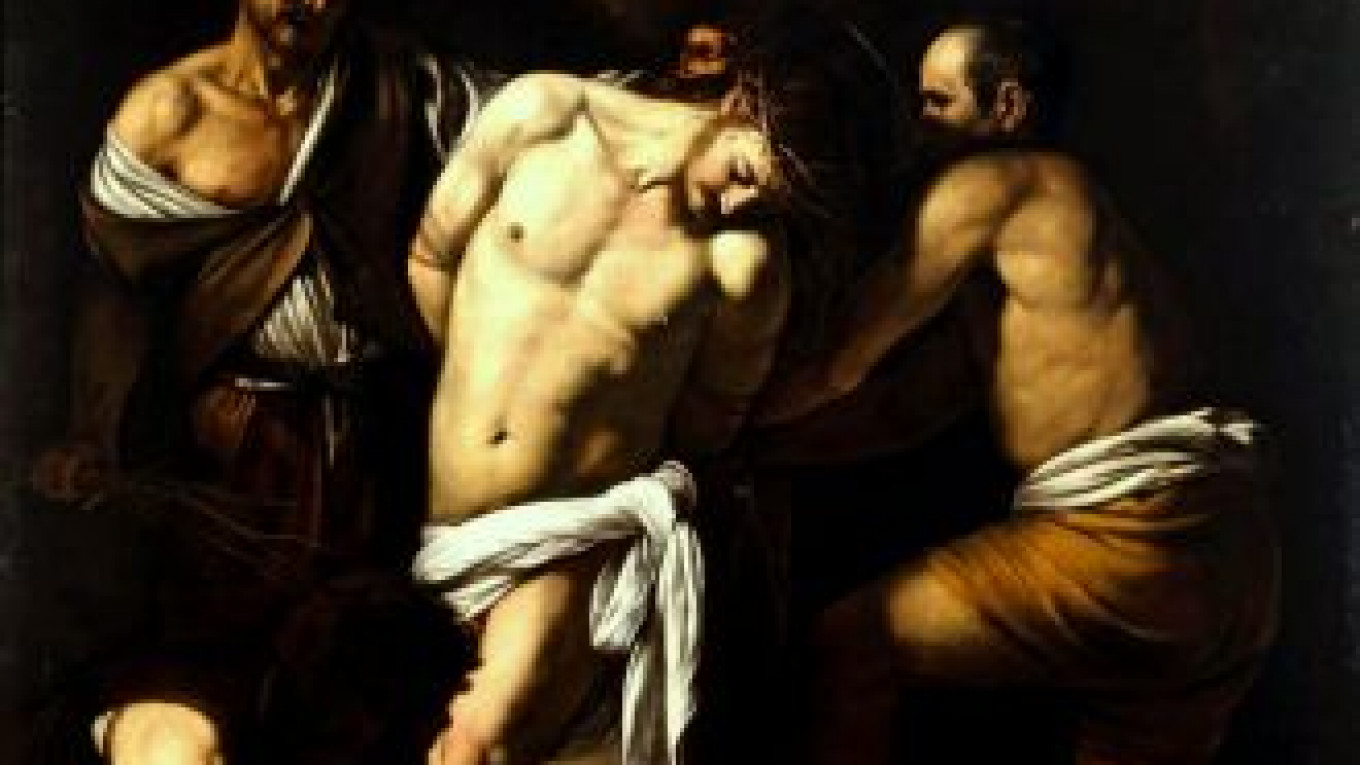

In his painting, the Milan-born artist is perhaps best known for using a technique known as chiaroscuro (Italian for “light-dark”) — in which light flows in from an unknown source, illuminating the focal point of the picture — to lend his work a particular dramatic intensity. Although neither the first nor last to employ this technique, it developed a special vibrancy under Caravaggio’s brush.

In the Moscow exhibition, the effect is rendered all the more pronounced by the museum curators’ sensitive arrangement of the 11 paintings in a dimly lit room. In this setting, the rays of light that Caravaggio uses to focus our attention seem even more intense, and his characters are set in even sharper relief.

For this reason, the divine light that enters from the right of the canvas and illuminates Saul in “The Conversion of St. Paul” (1601) is accented, powerfully evoking the revelatory moment the Roman soldier experiences on the road to Damascus.

The museum’s other on-loan exhibits exemplify more characteristic features of Caravaggio’s art. In “The Flagellation of Christ” (1607), the artist’s rejection of the idealized style espoused by his contemporaries is clear: One of Christ’s assailants is missing teeth, another is seen kicking his right leg from under him. Christ is not bowed in a graceful pose but contorted as he is knocked off balance, unlike in other artists’ interpretations of the same scene.

Similarly, “The Supper at Emmaus” (1606) illustrates the artist’s habit of displacing images of saints and martyrs from the center of the canvas and replacing them with ordinary men and women, warts and all. Gone are the idealized forms and religious tranquility of earlier artists, and traditional biblical scenes are reinterpreted and brought to life.

The exhibits are organized in loose chronological order, allowing the visitor to gauge Caravaggio’s development as an artist and compare his earlier studies of human form — such as “Boy With a Basket of Fruit” (c. 1593) — and later complex scenes, in which several characters are frozen in dramatic action.

It is here that Caravaggio’s tempestuous biography seeps into his work, for from 1606 onward — after the Vatican passed a death sentence over him — there is an added poignancy to his work. “The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula” (1610), for instance, captures the last moments of the young bride-to-be’s life as she is transfixed by an arrow. Here the pale light singling out Ursula highlights her isolation and the tragedy of her approaching death.

As biographer Francine Prose put it: Caravaggio’s life “is the closest thing we have to the myth of the sinner-saint, a myth that in these jaded and secular times we are almost ashamed to admit that we still long for and need.”

“Caravaggio: Paintings From Italian Collections and the Vatican” runs till Feb. 19 at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, 12 Volkhonka. Metro Kropotkinskaya.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.