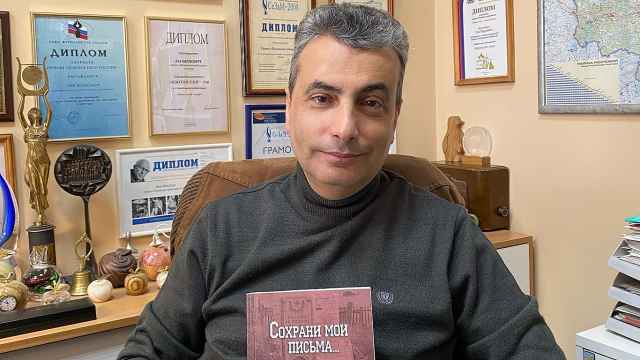

Art gallerist and former Kremlin adviser-turned-critic Marat Gelman has, for the first time in his decades-long career in the arts, stepped into the role of an artist himself.

His new series with the +-Comma art group, “First of All, It’s Beautiful” — a collection of images of nuclear mushroom clouds — explores the threat of nuclear war in the context of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

Gelman rose to prominence in the 1990s as the founder of one of Russia’s first private galleries and later served as director of the state-run Perm Museum of Contemporary Art from 2009-2013. The museum, one of the premier art institutions in the Volga region, was subject to police raids last year.

Having served as a Kremlin-aligned political consultant and a deputy director of state-run broadcaster Channel One in the early 2000s, Gelman has since become one of the regime’s cultural critics. Declared a “foreign agent” and added to Russia’s list of extremists and terrorists in 2024, he has lived in exile since 2014.

His and +-Comma's work will be shown at Artists Against the Kremlin, an upcoming exhibition co-organized by The Moscow Times in Amsterdam.

In this conversation, Gelman reflects on the role of art in the Russian anti-war movement and what it means to create culture in times of war and repression.

The Moscow Times: Could you tell us more about the idea behind your project?

Marat Gelman: Nuclear weapons are a tool of blackmail, meant primarily to scare people. The more we are afraid, the more powerful the blackmailer becomes. So, if you refuse to be afraid, if you declare that you feel no fear, you take the weapon away from the blackmailer. That’s why we make explosions beautiful, interesting. They resemble art from the past, the kind of art people love. Sometimes they even make you smile. And in this way, we resist this threat.

When [President Vladimir] Putin started his nuclear blackmail — and I believe I understand him quite well, I do think he could use nuclear weapons — I realized that if I simply spoke about it to my audience, I would be playing his game. Nuclear weapons exist and that’s a fact we have to learn to live with. Ideally, we should learn to live with them without displaying fear. I first realized that I was mortal when I was about 10 years old. At first, it shocked and scared me. But today I, like all of humanity, live a normal life and understand that death is also a source of inspiration. The very fact that I am mortal does not prevent me from living a normal life — if anything, it makes my life more meaningful. So, I decided to treat nuclear weapons the same way. They’ve already been invented, they’ve already been built, they exist. We must accept this.

Another important aspect is that this series was created with the help of artificial intelligence. In my works, I essentially explore the entire history of art. A nuclear explosion is, in a way, the return of the landscape. It’s almost like the final postmodernist project. AI hasn’t yet taken its first step toward creating new art, but it does allow us to take the last step in old art. Using AI, I can claim the entire history of art as my own. Appropriation has always been part of art, but such total appropriation was impossible before AI. So, for me, this is also important — this is, so to speak, the last project of the old art.

MT: Why did you decide to speak in the first person now and how do you feel in this role?

MG: Throughout my life, I’ve occasionally had the impulse to become an artist, but I hid it because it would have been a conflict of interest — I was either a gallery owner or a museum director. I felt that this blackmail situation was important. What really struck me was that the global community, by deliberately succumbing to this blackmail, reduced its support for Ukraine — ‘God forbid Putin loses, he might push the button.’

I realized that this was a situation where I couldn’t just pass the message on, couldn’t speak through other artists’ works. I had to speak in my own voice. My biography matters here — the fact that I worked for the authorities until 2002 and that I have some personal responsibility for what is happening now. This project has, let’s say, critics — some argue that ‘with this project, you normalize evil.’ So it’s a rather controversial project. That’s why I felt it had to be done in my own name, so I could respond to the criticism myself.

MT: You mentioned that this project has sparked mixed opinions and reactions. Do you think anti-war art can influence society, both in Russia and in Europe?

MG: Of course, an artist speaks to his audience. So an artist inevitably has an influence. First, artists declare that they are against the war. Second, they make anti-war arguments more visible, more tangible, sharper. It is especially important that these are Russian artists, because one of our major problems is the perception that ‘Russian’ means ‘pro-war,’ ‘pro-Putin.’ That perception is very harmful — it even hinders efforts to end the war. So, in terms of importance, I’d say the most crucial thing is that Russian artists’ voices are raised against the war.

How we process all of this is also important. Yes, we feel a certain guilt. Yes, we believe that everyone must take a stand against the war. We have no right to ignore it — unlike, say, an artist in France who can look the other way.

And there’s also the question of self-preservation. You see, an artist who follows the authorities loses themselves. An artist must be an independent thinker, someone who sides with the weak, who strives to integrate into the global art community, not to isolate themselves like the current authorities, and someone who looks to the future, not the past, like the current regime does. For an artist, opposing Putin’s Russia is a given — it’s what keeps you an artist. Those who don’t do that are no longer artists, they become mere decorators and craftsmen.

MT: Speaking of self-preservation as an artist, do artists and cultural figures who remain in Russia have any chance of maintaining their integrity?

MG: There’s a term now — ‘the new silent ones.’ It means that if you can’t leave or if there’s a risk that your statement could lead to arrest, you need to step back for a while. People have gone silent. Silence, inaction — that’s the minimal form of resistance, of not participating in evil. I know many honest people who have simply gone silent. At first, many thought this silence would be temporary. Young people have the underground route — apartment exhibitions, painting on walls at night, etc. The situation is harder for those who are part of the establishment because the authorities keep close watch on them. Many are simply looking for ways to leave. Overall, this situation does not encourage an artist to retain their place while not risking their lives or freedom in Russia.

MT: How would you describe the situation among artists who have left Russia?

MG: Of course, it’s extremely difficult for them. We’ve lost everything. We no longer have that background, that support system. But we help each other and that’s important.

Losing that ‘rear base’ has many downsides, but there’s one small advantage that I’m trying to focus on now. Since we’ve been stripped of the ability to live off our past achievements, we have only one chance left — to create new art. Otherwise, nothing will work.

Marat Gelman’s art will be displayed at the second edition of Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition organized by The Moscow Times and All Rights Reversed gallery at De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 15-Sept. 4.

Visit the exhibition website for more information.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.