My father, the Jewish Russian writer Grigory Baklanov (born Friedman in 1923), was 17 when in June 1941 the Nazis invaded the U.S.S.R. Although too young to be drafted and exempt from active duty by his employment, he managed to enlist and fought first as a soldier at the Northwestern Front and later as an artillery officer at the 3rd Ukrainian Front.

The atmosphere of those days when people without military training, barely armed, rose to defend their country can be compared with the current mood in Ukraine, where yesterday’s students became motivated fighters.

In 1943 they liberated the same regions where today Ukrainians confront Putin’s invading armies. Baklanov was badly wounded near Zaporizhzhia, but returned to the front after six months in hospitals. He later participated in the Jassy-Kishinev offensive, advancing with his artillery division to Bulgaria and then to Hungary, where heavy battles were fought near Székesfehérvár. In May 1945, in Austria, he heard the long-awaited news that the war was over. As he recounts in his memoir, “Life, Twice Given,” there was spontaneous firing into the air and drinking, but, disappointingly, little joy. When celebrating the war’s end, soldiers felt a painful void as they remembered friends who did not live to V-Day.

The war ended, but it continued to dwell within him. As he writes in his memoir, “I saw the war anew, all those years, and days, and hours, and months, while a single hour was often longer than many lives.” In his novels Baklanov recreated historical events that left few survivors. The battles in which he participated had not played a decisive role in the Second World War. They barely entered war chronicles and their participants were forgotten, so it was vital to leave a record:

… I could not allow for all that I had seen and known to disappear without a trace. I dreamed about it at night. And I already knew that the only way to get rid of it was to write.

Baklanov considered accuracy in depicting the war his primary task. Such books had a difficult path to publication because “truth from the trenches,” the term coined by Soviet critics, was not wanted. As Baklanov puts it succinctly, “Our truth is that war is inhumane.” After the war, Stalinists created a victorious version of events that no one was allowed to challenge. Stalin’s military purges, the destinies of millions who perished unknown or were crippled by war — these and other topics were then off-limits.

His 1959 novel, “An Inch of Land” (title of English translation: “The Foothold”), was attacked by official Soviet critics for its authentic depiction of the war, but was swiftly recognized abroad. Translated into 36 languages, it brought him international fame.

With his novel “July 1941,” he was among the first Soviet writers to show that Stalin’s Red Army purges on the eve of the war were responsible for devastating losses. Following initial publication in early 1965, when Khrushchev’s Thaw was ending, this novel was suppressed for 12 years.

Baklanov was always aware that he was lucky to survive the war that had killed so many of his generation. These young men, many still in their teens, had perished “without a trace,” leaving no progeny. In his words, one of the most tragic consequences of the war was their complete disappearance. In his fiction, Baklanov often used surnames of fallen friends, remarking: “This may not be his actual story, but let his name live on.”

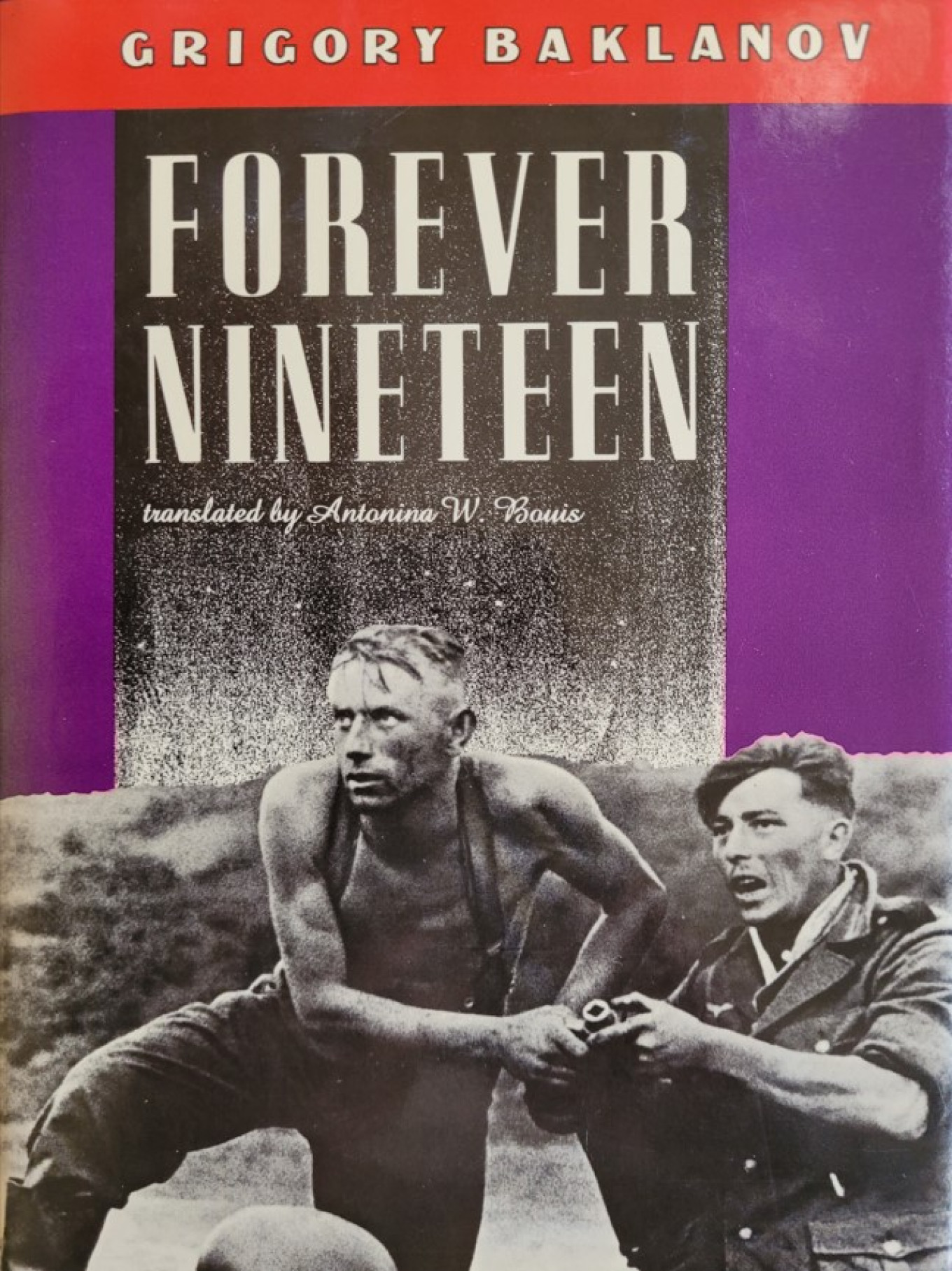

His 1979 novel “Forever Nineteen,” translated by Antonina Bouis, was a tribute to the men who remained forever young. As he wrote in the preface to an American edition, “We had twenty boys and twenty girls in our class. Almost all the boys went to the front, but I was the only one to return alive. Our city, Voronezh, the ancient Russian city on the steppes, perished under the bombs, was destroyed by the artillery, and was blown up by the Germans when they retreated. I came back after the war, in the winter of 1946. None of my family was there. …And only in our memory are people who no longer exist still alive and still young. I wanted them to come alive when I wrote this book. I wanted people living now to care about them as friends, as family, as brothers.”

The novels “Forever Nineteen” and “The Foothold,” are thematically linked. In fact, Baklanov devised the idea for “Forever Nineteen” during the shooting of the film based on “The Foothold,” written two decades earlier. When in 1965 trenches were dug in the area of a former bridgehead, the film crew unearthed a soldier’s skeleton. Having witnessed the event, Baklanov later used it for the opening of “Forever Nineteen.”

Baklanov wrote not solely about the war, but always with thought for his generation. While “The Foothold” and “Forever Nineteen” portrayed his cohorts in their youth, his 1995 novel “And Then Come the Marauders” takes the reader through the epochs of Stalin, Brezhnev, Gorbachev’s perestroika, and the collapse of the U.S.S.R. The novel’s idea is reflected in the protagonist’s words: “After a combat the battlefield belongs to marauders.” Through this image, the author explains how successive regimes, beginning with Stalin’s, used Soviet victory in the war for political gain. The harshest work he had ever written, it deals with the reemergence of Stalinism and neo-fascism in post-Soviet Russia.

In 1986, during the Gorbachev era, Baklanov joined the fight for press freedom, becoming editor-in-chief of the literary magazine “Znamya.” Under his editorship, the magazine’s circulation rose to 1 million. It published some of the best literature that Soviet authorities had suppressed for decades. Baklanov was hoping that his generation had saved the world from the reemergence of twentieth-century calamities. He death in 2009 saved him from learning about Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the bloodiest conflict in Europe since the Second World War.

Below are two excerpts from the opening and conclusion of “Forever Nineteen.”

Alexandra Popoff

Forever Nineteen

The living stood at the edge of the trench. He was inside. Nothing about him that in life distinguishes one person from another had survived. It was impossible to tell who he had been: one of our soldiers? a German? But the teeth were young and strong.

The shovel struck something — a belt buckle, oxidized green and packed with sand, with a star on it. They passed it around carefully. It told them he was one of ours, most likely an officer.

It began to rain. The rain pattered on the backs and shoulders of the military shirts the actors were wearing to break in before the filming began. The battles in this area had taken place over thirty years ago, before many of these people were born, and for all these years he had lain in the trench. Spring waters and rains had seeped down to him in the ground and were sucked out again by the roots of trees and grasses. Now the rain was washing him. Drops dripped from his dark eye sockets, leaving topsoil traces; water poured along the exposed collarbones, the wet ribs, washing away sand and dirt from places where lungs had once breathed and a heart had beaten. The young teeth, wet in the rain, took on a lifelike glistening.

“Cover him with a cape,” the director said. He had brought his crew here to make a movie about World War II and they were digging new trenches where the old ones, long ago filled in and covered with grass, had been. Workmen stretched out a cape and made a tent. The summer rain banged on it, seeming to come down harder. The sun was shining, and steam rose from the earth. After a rain like that, all living things spurt into growth.

The night stars shone brightly across the entire sky. As he had over thirty years ago, he lay in an open trench. The August stars above tore away from their spots and fell, leaving bright trails in the sky. In the morning the sun rose over his shoulder. It rose over cities that had not been there then, and over plains that had been forests. It rose, as usual, warming the living.

***

The first-aid wagon came by to load the wounded. Having decided to go on the next trip, Tretyakov* sat on the porch steps with his coat over his shoulders, watching the paramedic, a young, pushy, and sharp woman. The driver jumped at the sound of her voice and hurried to obey her orders — and did it all wrong.

They loaded a wounded man. They put him in the straw at the bottom of the wagon and he moaned weakly. Men hobbled over on their own, trying to appear more pathetic than they were. Tretyakov took his cigarette lighter out of his pocket and lit up. The pain, dulled by novocaine, was not too bad. He could take pain like that; there would be worse pain ahead. They would be pulling the bandages from his fresh wound over and over until it started suppurating and the bandage would come off on its own. He could see the whole road he would have to travel. This time they would probably have to put his arm in a cast. He remembered the fellow in the train who dug out the maggots from his wound. That would be hard, when it began itching under the cast.

“Lieutenant! Come on!” The doctor was calling him to the wagon. Having prepared himself for the second trip, Tretyakov was happy. He came over.

“Get in,” the doctor said. “Go.” And he clapped him on the back carefully. Now that he was being sent to the rear, he felt a vague sense of guilt. He saw the elderly soldier sitting on the ground, his freshly bandaged leg stretched out before him. Tretyakov hesitated.

“Take him,” he said quietly to the doctor. “I can walk.”

The soldier heard him and came over, hobbling. He climbed in like a man claiming his due and yelled at the driver. “What are you waiting for? Let’s go!”

“Don’t give orders!” the paramedic shouted. She was sitting next to the driver. “Some commander… Watch it, or I’ll send you packing!” He pretended not to hear. She moved over on the seat and said angrily to Tretyakov, “Sit down, Lieutenant. Everyone thinks he is in charge here.”

He shook hands with the doctor, then looked around for the last time and got in. There. Life had come full circle again.

He was traveling with his back to the front. His platoon, the war — all that was left behind. The steppe was in a dusty haze, the shadows of clouds flew over it, and hills or mountains rose like light-blue visions. And overhead, in the high, blinding sky, were row after row of fluffy white clouds.

Life was so wonderful, Lord, so glorious! It was like seeing it all for the first time. The shadow of a cloud rolled onto the horses’ backs, and he felt it with his face and eyes closed in the sun.

“Slow down,” he said to the driver. He got off and walked. His wound had been shaken up and it hurt again, but he knew that the wound would hurt for a while and then heal. Now his soul was at peace. The paramedic looked down at him with her sleepless eyes and moved over to his spot on the seat.

“Been at war long?” he asked, hoping to forget his pain by conversation.

She yawned. “Get a smoke.” She was very young, with plump lips and a small mouth. She lit her cigarette from the driver’s and coughed harshly on the first drag. The shadow of the cloud traveling over the steppe covered the valley. Something made Tretyakov wary. He did not know what it was, but he had the feeling of danger. Still feeing responsible and in command, he had watched the area, from above when he had been riding and now as he walked.

The horses stepped down the road, the driver urged them on with the reins, the wounded men smoked, and he walked alongside, holding on to the wagon. He looked up at the paramedic, he did not want to worry her needlessly.

The shadow moved; the sun lit up the valley. He had been worried for nothing.

“Been at war long?” Tretyakov asked, forgetting he had already asked.

“A long time,” she said, her voice clear after the cough. “Everyone in my family is in the war. My big sister left right after her husband was killed. My brother, too. My mother and kid brother are at home, waiting for letters.”

He walked along and continued to look up at her. What if she were Sasha? or Lyalya?**

He never heard the machine gun. He was hit, knocked off his feet, and fell. It happened in an instant. Lying on the ground, he saw the horses run off down the slope, the young paramedic grab the reins from the driver, and he measured the growing distance separating him from them. He shot at random. More machine-gun fire followed. He had time to notice where the fire was coming from, to think that he was in a bad place, on the road, very visible, that he should roll into the gully. But at that instant something moved ahead of him. The world contracted. He saw it through the sight on his gun. There, on the muzzle of his gun, at the end of his extended arm, it moved again, something smoky gray rising against the sky. Tretyakov fired.

When the paramedic stopped the horses and looked back at the spot where they had been ambushed and where Tretyakov had fallen, there was nothing there. Only the cloud of an explosion rose from the earth. And row upon row of blindingly white clouds, given wing by the wind, floated in the heavens.

* Tretyakov: the main protagonist of the novel, who perishes at nineteen.

**Sasha is Tretyakov's girlfriend and Lyalya is his sister.

Excerpted from “Forever Nineteen” by Grigory Baklanov. First published in Russian in 1979 under the title “Naveki devyatnadtsatiletnie.” Translated by Antonina Bouis and published by J.B. Lippincott, 1989. English translation copyright © 1989 by Antonina Bouis. Used by permission. All rights reserved. A review of the book when it was released can be found here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.