The first high-profile attempt by a group of Russian billionaires to get European sanctions against them lifted with help from the country’s political opposition has ended in bitter acrimony and the resignation of Leonid Volkov — a close ally of jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny — from his position as chairman of the Anti-Corruption Foundation.

How did this happen? Reports emerged last week that members of Russia's opposition have been making overtures to Western officials since the fall, requesting that sanctions on senior managers of Alfa Group, a consortium that owns the largest retailer and private bank in Russia, be lifted.

The tycoons in question are Mikhail Fridman, Petr Aven, German Khan and Alexei Kuzmichev. None of them have publicly condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

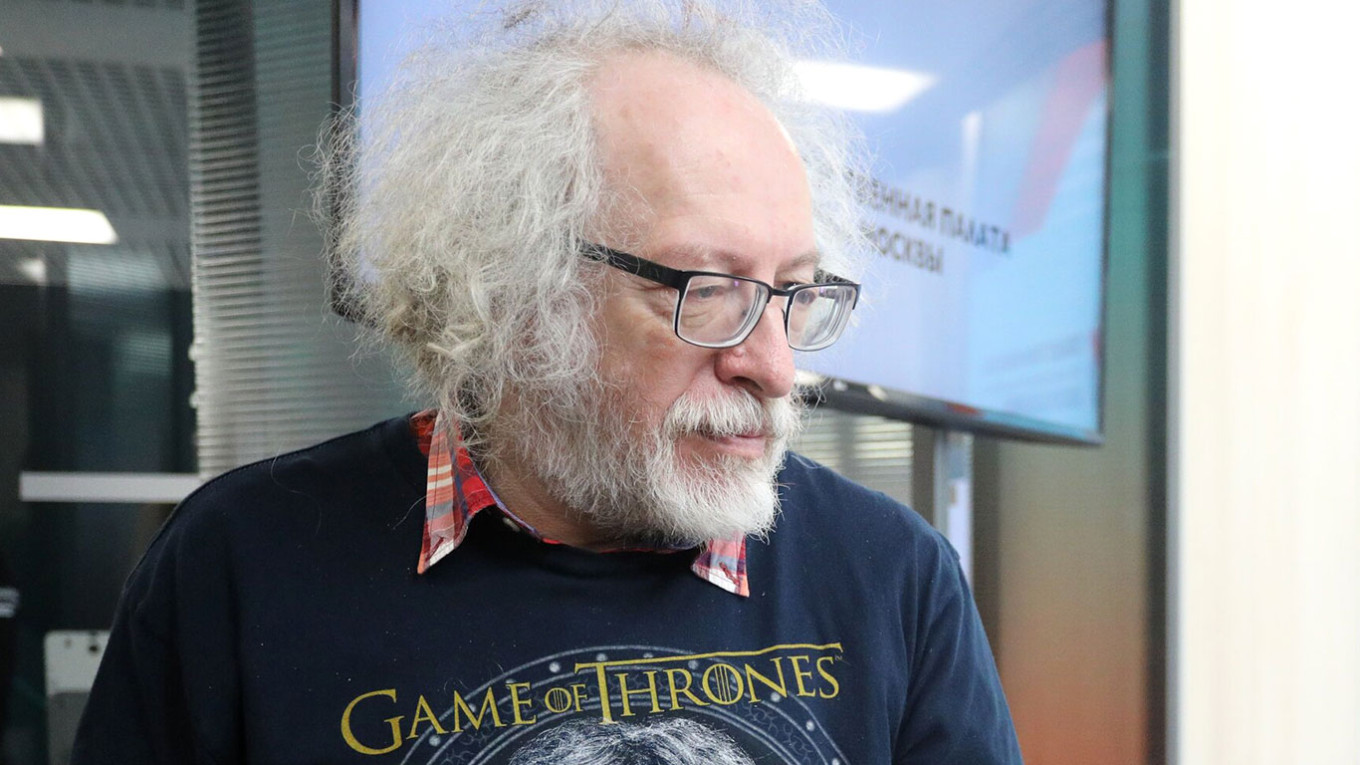

The news of opposition figures being used in Alfa Group’s lobbying attempt went largely unnoticed until a new twist in the long-running feud between supporters of Navalny and Alexei Venediktov, the editor-in-chief of liberal radio station Ekho Moskvy before it was forced to close last year because of wartime censorship laws.

While the two groups have been quarreling for some time — accusing each other of being agents of the Kremlin — Navalny's Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) released a report earlier this week alleging Venediktov had received hundreds of millions of rubles in funding from Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin for a magazine that he ran. Venediktov, who denied all wrongdoing, took his revenge by publishing a photograph of a letter to European Commission officials requesting the removal of sanctions on Alfa Group's senior management. The letter was signed by several Russian journalists and members of the opposition, including Volkov.

Initially, Volkov said his signature had been photoshopped. But it soon transpired that Volkov had, indeed, written a letter in defense of the Alfa Group that was submitted to EU officials.

In a statement on Thursday, Volkov conceded that signing such a letter had been a mistake. He announced he would be “taking a break” as the chairman of the FBK, Russia's most high-profile opposition group.

The incident is reminiscent of a scandal in 2011 when Venediktov was reported to have been among a group of opposition leaders and journalists who drank whiskey at a meeting with officials including influential Kremlin official Alexei Gromov. The topic of the discussion was the opposition protests that were raging at the time and the group allegedly came to an agreement about the location of an opposition rally in Moscow. This episode caused deep anger when it was reported a year later, with many activists accusing Venediktov of conspiring with the government.

In other words, Venediktov knows what it’s like to be in Volkov’s shoes — and be the target of angry allegations of betrayal.

A particularly dubious part of the various letters submitted in defense of Alfa Group management is the claim that they have never met Putin. The letters state that the businesses owned by Fridman and his partners cannot be considered close to the Russian government, Putin, or anyone in Russia's corridors of power.

This is an interesting — frankly astonishing — claim. One only has to recall how, in 2013, Alfa and their partners received an eye-watering $28 billion from state-owned oil giant Rosneft for their share in a joint venture with British oil company BP. The head of Rosneft was none other than Igor Sechin, a close confidant of Putin.

This deal came after Alfa Group, in typical litigious fashion, helped block a groundbreaking multi-billion dollar Arctic exploration tie-up between Rosneft and BP. At a bare minimum, the deal demonstrated the immense lobbying capabilities of Fridman’s team.

Could a state-owned company like Rosneft have paid out $28 billion without Putin’s personal agreement? Of course not. In an interview with the Financial Times in 2012, even Sechin admitted that he had sought approval from Putin.

The Rosneft deal is just one example of Alfa Group’s close connections with the Kremlin — there are many others. Our sources said that, while Fridman was Alfa Group’s pointman for the company’s contacts with Dmitry Medvedev during his time as Russian president, Aven was responsible for managing relations with Putin.

It’s one thing to protect Russian tycoons from Western sanctions on the grounds that they built their businesses largely independent of the state — banker Oleg Tinkov, for example. But the situation with Alfa Group is far more complicated.

Even if Fridman and Aven manage to sell their stakes in Alfa Group — as the Financial Times reported Friday — that does not wipe the slate clean when it comes what appears to be their historic high-level links with Kremlin officials.

What conclusions can we draw? On the one hand, Volkov deserves respect for owning up to his mistakes. On the other hand, the scandal will do enormous damage to the reputation of FBK and strengthen rumors — long denied by Navalny’s colleagues — of secret collaboration between FBK and Alfa Group.

How best to deal with personal sanctions against members of the Russian elite is a question that remains unanswered. Volkov is right when he says that personal sanctions only make billionaires, state managers, and officials rally around Putin. And this means that such sanctions are not hastening the end of the regime.

It’s both surprising — and comical — that the first attempts by Kremlin-linked Russian billionaires to get personal sanctions against them lifted with the help of the country’s opposition ignited such a bitter feud.

Fridman, no doubt, regrets the whole affair.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.