Cheese in Russia is more than cheese. For some reason, throughout our history, it has always been some kind of symbol — either fealty to national values, or self-reliance, or even an example of free thinking.

The thesis popular today in pro-Putin circles is that Russian cheese is the oldest and most delicious cheese in the world and that Europe stole Parmesan from Russians. This is, of course, nothing more than a patriotic lie — something we have gotten used to hearing from this crowd. The justification for this lie is a wedding rite mentioned in "Domostroi" when a friend of the bridegroom would break a chunk of cheese over the new husband's head. "You see!" they exclaim. “In Russia we had hard cheese back in the 16th century!"

In fact, of course, it means nothing. Try breaking a chunk of Cheddar or Tilsiter in your hands. The wedding would have turned into a circus. But anyone could break a piece of soft young cheese like Bryndza or Adygeisky. And that just confirms the old truth: there were no hard cheeses in medieval Russia.

Not only were there no hard cheeses back then — there couldn't have been. We have ample proof of that in the observations left by many foreign travelers and diplomats who visited Moscow in 16th-17th centuries. They noted that at that time it was strictly forbidden to slaughter calves and eat veal. The prohibition was universal and almost religious in nature. Ivan the Terrible even ordered that workers who were building a fortress in Vologda be thrown into a fire because they were so hungry they slaughtered a calf.

What do calves have to do with cheese? Simple. To produce hard cheese, you need an enzyme derived from the stomachs of calves who are still nursing. The enzyme breaks down the milk in the digestive process. So our ancestors were only introduced to hard cheese in the era of Peter the Great, when all these prohibitions slowly receded into the past and foreign cheesemakers began to come to Russia.

However, it took a whole century for the first cheese factory to appear in the country. It was opened in 1812 outside Moscow in the village of Lotoshino, owned by Prince Ivan Meshchersky. A foreigner, the Swiss master Johannes Muller, was invited to oversee production. Twenty years later Alexander Pushkin would write about "fine Swiss cheese from Lotoshino."

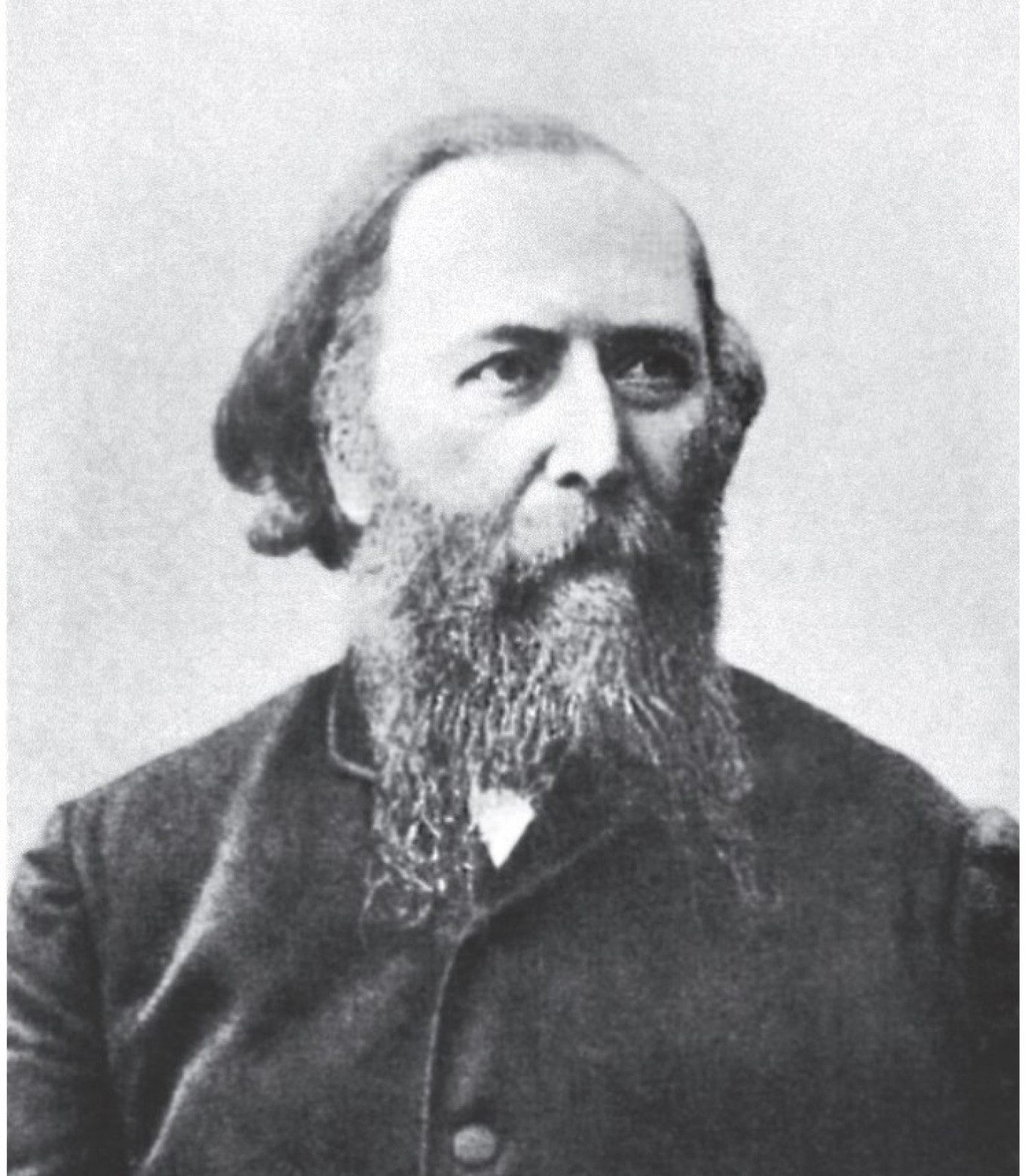

In the second half of the 19th century the center of cheese production moved to the Vologda province. Cooperative cheese factories were founded there through the efforts of Nikolai Vereshchagin (brother of the famous painter of battle scenes). Long-ripening Swiss cheese did not take root here, as the milk didn’t have the right composition and purity for it. But it was perfect for making Cheshire cheese and varieties of Dutch cheese.

At first foreign-made hard cheeses had higher quality than ours. But Vereshchagin didn’t try to copy Parmesan or Emmentaler. He created and named new Russian brands. All the cheeses such as Kostroma, Yaroslavl, Uglich, Poshekhonye, and so on came from that era. By the beginning of the 20th century Russia produced about 100 native cheeses. And this was when there were no bans on cheese imports!

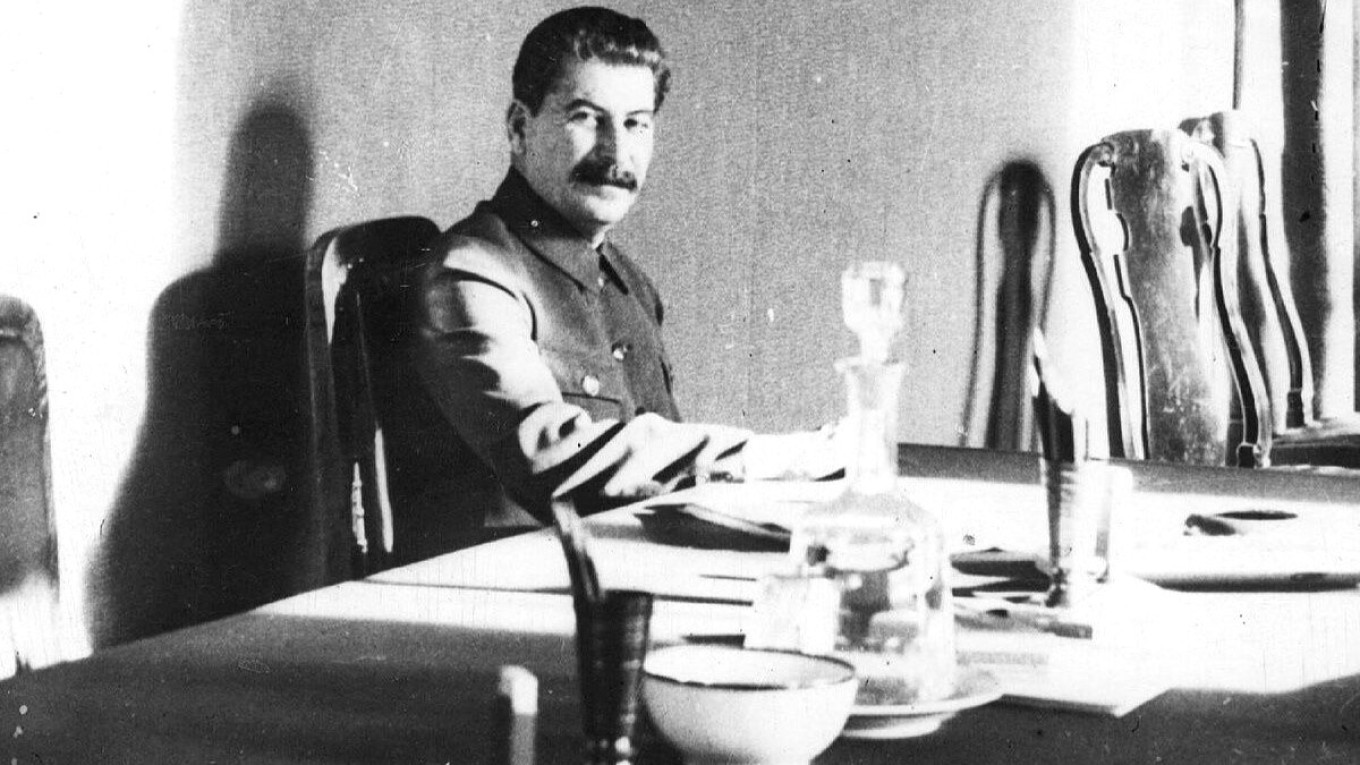

Our cheese world changed a great deal during the Soviet period, when many new brands and types of cheese were created. The apotheosis of this was the creation of "Soviet" cheese, which got its name due to Stalin's gastronomic illiteracy. Once at breakfast he was served a cheese that he liked very much. "What kind of cheese is this?" he asked the waitress. "Swiss," she replied. "Can't we make our own cheese?" Stalin asked indignantly. He didn’t know that the "Swiss" cheese on his table was "Swiss" in name only. It had been made in Altai.

The U.S.S.R. produced even more new brands of cheese. But as time when on, another problem arose: milk. In those lean years, farmers had short conversations with cows. The foreman would come in the morning and ask the cow, “Well, my sweet, will you give me milk today or is it time you gave us meat?” Any cow that wasn't producing a lot of milk was sent to the slaughterhouse. No one was testing the milk to see if it would be good for cheese-making.

And so we arrived at perestroika with a deficit of cheese. Just like there were 50 types of sausages no one ever saw, all those mysterious cheese names were but a dream for late Soviet-era consumer. If they remembered them at all, it was with an unkind word for the Soviet leaders. During the famine years of 1989 and 1990, most of the dairy herd in the country was simply sent to the slaughterhouse and eaten. Cheese imports from Europe were a salvation, as was the gastronomic school that we had to go through after 70 years of Soviet isolation.

The results of the current round of self-isolation were completely predictable. Our fellow citizens who survived the Soviet Union know very well what happens to anyone who supposedly worships the West. The words "liberal" and "Parmesan" have become almost synonymous. But cheese in Russia, as we have said, is more than cheese. So accustomed to Parmesan and Roquefort were the Russian authorities that they didn’t even notice that Russian cheesemakers were trying to copy those "God-awful" European varieties of cheese. What else could Russian cheesemakers do? If you like Parmesan, buy our domestic, highly spiritual cheese. Does it smell a little like manure? That’s not true. It’s Russian spirituality coming through.

The absence of cheese in ancient Russian cuisine meant that there were virtually no domestic recipes for cheese until the 19th century. We can only speculate what ancient Russian cheese was like. We think it was probably not very different from today's cheeses made in the Caucasus, like suluguni, for example. And where there is suluguni, there is the Georgian pie called khachapuri. There are many variants of khachapuri — each Georgian region has its own. We like this recipe, which has its own name: pennovani.

Pennovani

This is a kind of khachapuri that can be quickly and deliciously prepared at home. Like all cheese pies, these flavorful, airy envelopes of puff pastry filled with suluguni are best eaten hot. If you don't have suluguni, lightly salted mozzarella will work as a substitute, or you can mix mozzarella with feta cheese.

You can use either frozen yeast or no-yeast puff pastry.

Ingredients

- 500 g (1.1 lb) puff pastry

- 300 g (10.5 oz) suluguni cheese

- 2 eggs (I egg for the filling, one for basting the dough)

- A pinch each of nutmeg, ground coriander and dried basil.

Instructions

- Defrost the dough according to the instructions on the package.

- Prepare the filling. Grate the cheese, add the egg, spices and mix well.

- Preheat oven to 190°C/ 375°F.

- Roll out the dough and cut into 8 squares.

- In the middle of each square put 2 tablespoons of filling and close by pulling the four corners to the center, making a dough envelope. Press well to seal.

- Lightly beat the second egg with a fork and brush over the pennovani.

- Bake in the pre-heated oven for 35 minutes.

Serve hot.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.