Today if you want to really outrage the Russian Foreign Ministry, just tell them that borshch is Ukrainian. Even soccer fans' notorious and obscene chant about Putin is less painful to Russia’s professional patriots than having to admit that there is Kievan, Poltavan, and Chernigov borshch.

When someone says the word "borshch," we all imagine an appetizing bowl full of hot, rich, beet-colored soup. But this image only took hold in the last three centuries. Before that, borshch was a term that each national group understood in their own way.

On the historical territory of Ukraine, since the end of the 16th century borshch has been unthinkable without beets. In Central Russia at that time borshch was a rather tart soup, flavored with sour cabbage leaves, with beets (or rather, their leaves) as optional ingredients. Vladimir Dahl even mentions borshch with mushrooms. Polish white borshch is impossible without sourdough starter, smoked sausage and horseradish.

But the dish itself has evolved, too. The inclusion of potatoes and tomatoes is only a small part of this process. In Russia, for example, a much greater contribution was made by the establishment of a national Soviet cuisine. That's when the menus of every restaurant or cafeteria added Ukrainian, Moscow, and summer borshch. Ukrainian borshch is traditionally garnished with minced bacon or salted meat and garlic; Moscow borshch contains meat; and summer borshch is made with young beets, both stems and leaves.

In Ukraine there have always been many types of borshch. So the culture of cooking Ukrainian borshch is quite rightly included today in the list of countries' intangible heritage recognized by UNESCO. If Russian officials were not so busy with their eternal complaints about Russophobia, maybe the culture of Russian borshch would be recognized internationally as well. But there is no point discussing this; the criminal war has eliminated many prospects for Russian culture.

However, Russia had another borshch: Navy Borsch. It was the spiciest borshch, made with smoked pork and hot pepper. It might be surprising, but this recipe is a striking example of the synthesis of Russian and Ukrainian cuisine.

The appearance of Navy Borshch is associated with Admiral Stepan Makarov (1848-1904). When he became commander of the port of Kronstadt (actually a naval base), in addition to the ships he began to command the coastal units and the garrisons. During inspections the Admiral encountered numerous complaints about the quality of food.

Feeding the navy soon became one of his chief concerns. He considered the quality of the sailor's soup to be an indicator of the commander's attitude toward his crew. "Sailor's cabbage soup," Makarov liked to say, "should be so appetizing and rich that any gentleman, catching the scent of it cooking, would want to taste it.”

In his 1901 annual report Makarov devoted several pages to describing how he made the soup to get such good results. "Since the fall of 1900," the report says, "I have undertaken a series of tests to achieve a better flavor. To this end Dr. Bogolyubov was sent to Sevastopol, and, in addition, a cook was transferred from there. Recipes were tested by some crews and in the naval hospital.”

Here it should be noted that Makarov's career took place in almost all the fleets of the Russian Empire. And it was hardly a secret for him that sailors in the Black Sea Fleet were fed better. A whole group of specialists — suppliers, logistics officers, cooks — were sent to Sevastopol. It soon became clear that tomatoes needed to be added to improve the taste. The exact proportions of vegetables and cereals for the first course were brought to the Baltic Sea fleet. All this work resulted in an order for the fleet: "On the Preparation of Meals," printed in a separate brochure and sent to all Baltic Fleet ships.

Since this recipe originated in the south, it was called “borshch.” And ever since that day, Navy Borshch has been an integral part of the seaman’s table and a model of a nourishing meal. When sailors today sit down to dinner, they can only remember Admiral Makarov with a kind word.

In Soviet times, Navy Borshch went from being a dish served to military men at sea to being a dish widely served in public restaurants and cafes. In 1955 it appeared in the famous book "Culinary Arts” and in many collections of recipes for public catering.

Today, Navy Borshch is more a memory of the days of the U.S.S.R. It is generally served in pseudo "Soviet"restaurants or in cities connected with the fleet in some way. But nothing prevents us from making this tasty and fragrant soup at home.

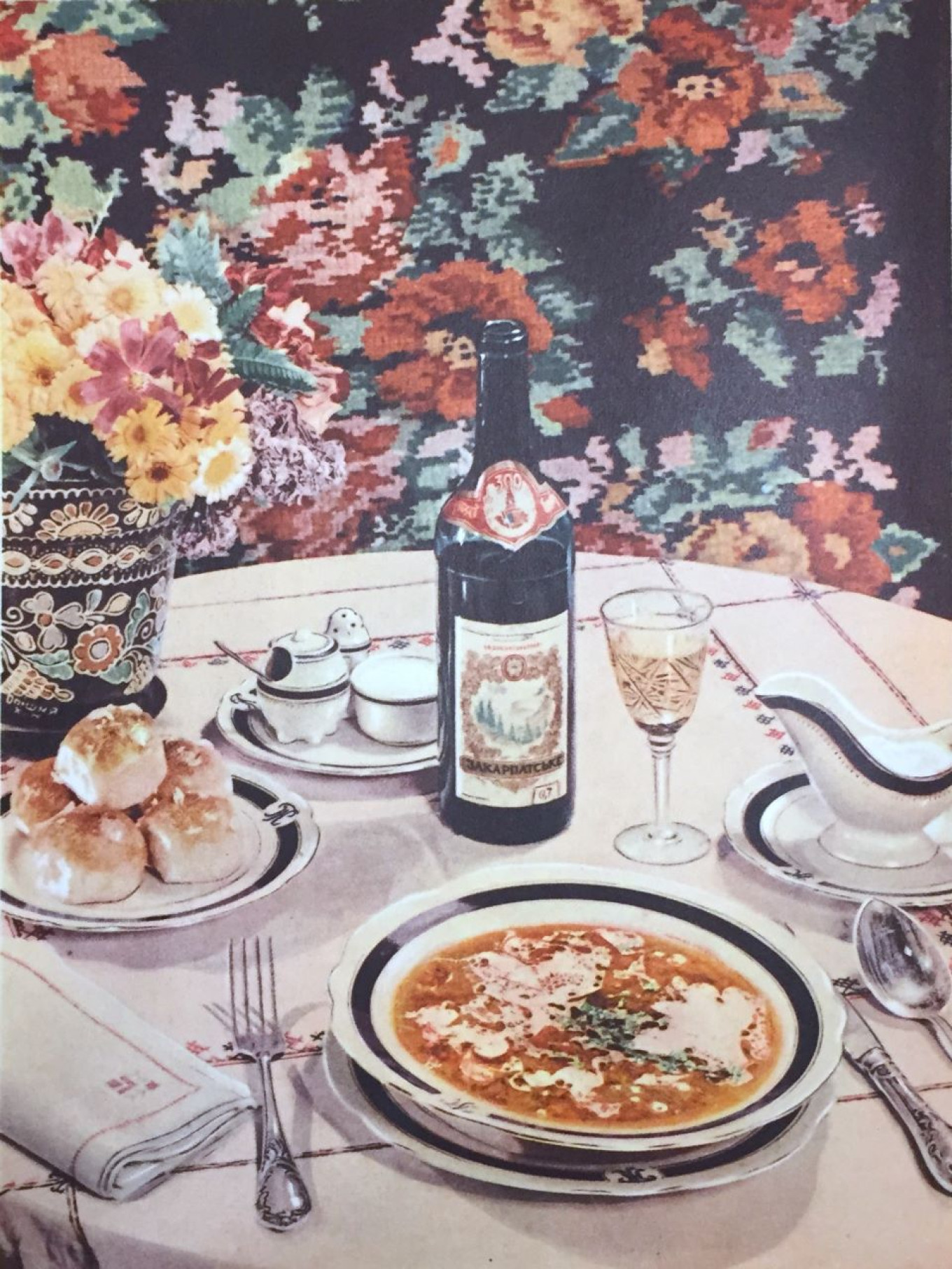

Navy Borshch is served with buckwheat or krupenik (a casserole made of buckwheat porridge). What distinguishes it is how the cabbage is cut — in 2-3 cm squares. To make it thick and filling, the classic recipe used a flour slurry as a thickener. But now that's unnecessary.

Navy Borshch

Ingredients

- 800 g (1.8 lb) beef brisket

- 320 g (11 oz) bacon or salted meat

- 500 g (1.1 lb) beets

- 250 g (1/2 lb) cabbage

- 400 g (14 oz) potatoes

- 130 g (4.5 oz) carrots

- 120 g (4.2 oz) onions

- 100 g (3.5 oz) parsnip or parsley root

- 80 g (2.8 oz or 3 Tbsp) tomato puree

- 40 g (1.5 oz) lard - clarified pork fat

- 25 g (2 Tbsp) sugar

- 35-40 ml (2 ½ to 2 ¾ Tbsp) 3% vinegar

- 5 cloves of garlic

- salt, hot pepper, spices, herbs to taste

- sour cream for garnish

Instructions

- Rinse brisket, put it in a pot, cover with water and simmer to make a broth. About 30-40 minutes before the broth is ready (to your taste), add diced bacon or salted meat. Season with salt to taste.

- Peel the beets, put in a separate pot and just cover them with hot water; add vinegar to retain color and boil the beets until tender. Once cooled, chop the beets. Don’t discard the liquid; later it is added to the finished borshch.

- Chop the carrots, onions, and parsnip or parsley root and fry in fat.

- Chop the fresh cabbage into squares about 2-3 cm. Cut the potatoes into smaller cubes.

- Strain the hot broth and pour it back into the pot. Add the cabbage and potatoes. After 15 minutes add the root vegetables.

- Five minutes before the vegetables are done, add the seasonings (herbs and spices to taste).

- Season the borshch with salt, sugar, vinegar to taste.

- Add the liquid in which beets were boiled to the borshch.

- Serve Navy Borshch with sour cream, greens, bits of cooked salted meat or bacon and cooked buckwheat groats.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.