Zhzhyonka (жжёнка) may look like a series of typos and be hard for non-Russian speakers to pronounce. But zhzhyonka is a legend of pre-Revolutionary Russian life. It isn’t just a drink — it’s a relic of a long-lost culture and its customs.

So what is this unpronounceable drink? The two letters ж at the beginning stand for the double heating process (жечь is to burn) this cocktail is famous for. Zhzhyonka is a mixture of various kinds of alcohol, both wines and stronger alcohol (rum and cognac) that is heated it as it made. And then hot sugar that has soaked up a strong liquor is dripped on top of the alcohol mixture. This burnt punch packs a double punch!

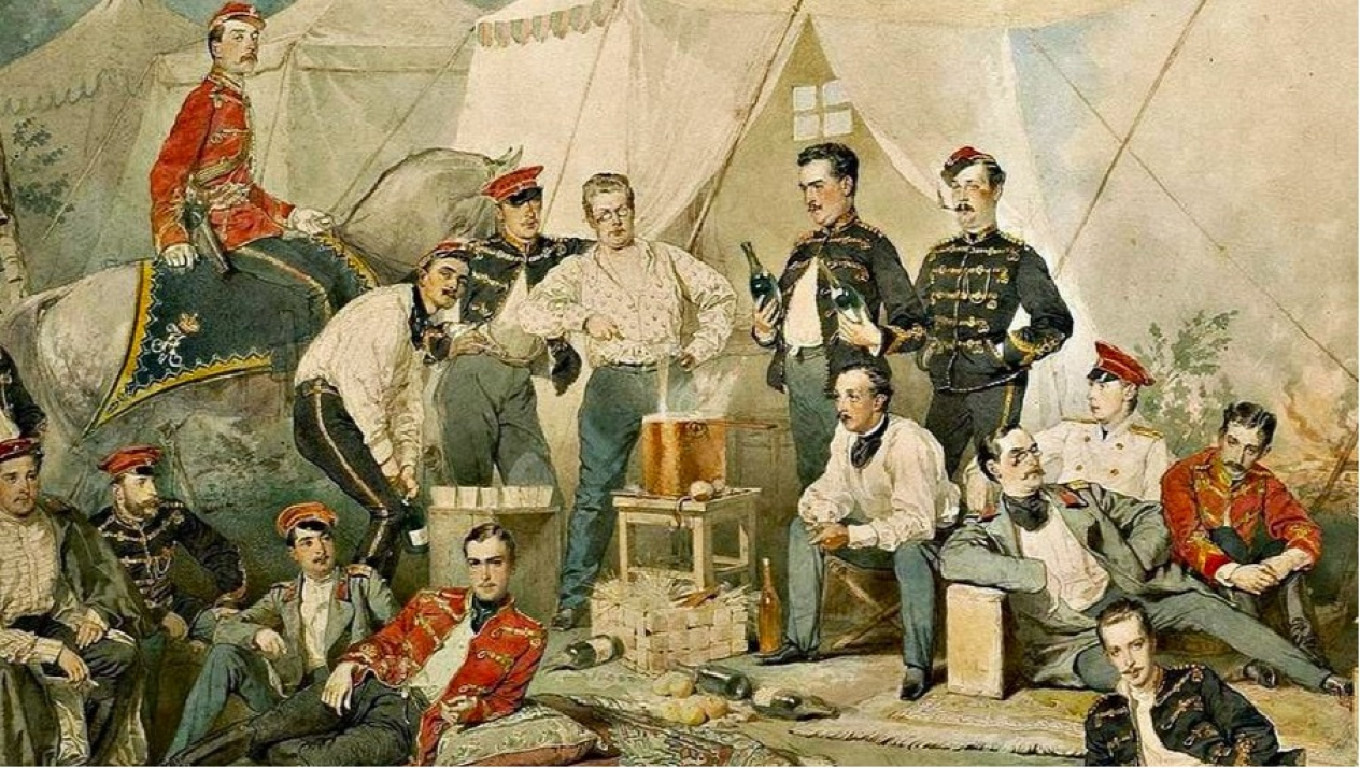

Its beautiful preparation and aroma fit literary descriptions of the Russian soul: dashing, ready to take risks, and having a weakness for flashy appearances. Perhaps for this reason burnt punch was the traditional drink of the Hussars, the elite of the Russian army, famous for their prowess and daring. It’s not hard to imagine hussars in tight pants, braided jackets, fur capes over one shoulder and tall visored hats on their heads standing at a cauldron of cognac and setting it alight! Why not? They had just come from bathing their horses in champagne.

This Hussar recipe was intricate and expensive. As Nikolai Popov noted in his book "Memoirs of an Old Cavalryman" published in 1891, several bottles of white rum were poured into a copper basin or a bowl and topped with oranges and spices. Large pieces of sugar were placed on saber blades that were laid over the cauldron, and the rum was set on fire. When the sugar had completely melted into the wine, they poured in champagne or good wine from Chateau Lafite. The mixture was delicious but dangerous. "One glass was enough," the officer recalled, "to get you intoxicated. After two glasses of this punch, a weak subject would lose the ability to move his tongue and was reduced to senseless mooing and cooing. After the third glass, his limbs were paralyzed and he would collapse under the table like a corpse. Stronger men experience a strange kind of ecstasy that awakened destructive and even violent instincts in them.”

These scenes are repeated from one late 19th century memoir to another. Russian poet and prose writer Vsevolod Krestovsky (1839-1895), who wrote the history of several lancer regiments and was attached to the headquarters of the active army during the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878, left a poetic description of zhzhyonka:

"The mustachioed Major, a very experienced brewer of burnt punch, crossed two saber blades over the cauldron. In the middle where they crossed he put a block of sugar and began to douse it with clear golden brandy. Then he crumbled two vanilla beans into the cauldron, and the alcohol burst into a faint bluish flame. The sugar melted and dripped into the mixture with a hiss and a crackle of fiery droplets. The mustachioed Major took a bottle of red wine and carefully, so as not to extinguish the flames, poured it in with an equal quantity of brandy and began to stir the burning liquid with a large soup spoon. The fragrant hot inferno of alcoholic fumes made everyone’s head swim..."

But that is the romance of the evening, so to speak. In the morning, life turns pragmatic. Made of red and white wine, cognac, sherry, rum, etc., too much of this burnt punch predictably caused quite unpleasant consequences. Even experienced drinkers found themselves with hangovers. "The next day — headache, nausea. It's obviously from the mix of alcohol in the zhzhyonka. The sufferers sincerely vow never to drink this poisonous drink again,” said the hero in Alexander Herzen's novel "My Past and Thoughts.”

This romantic drink predictably spread far beyond the military. It was a favorite drink of the "golden" youth in the capitals and prepared for holidays in affluent families. However, for ordinary citizens it was too expensive. It would be wrong to think that zhzhyonka was merely a drink for men on military missions, or something frivolous one might drink at the dacha. It was served (in fact prepared at the table) during a diplomatic reception hosted by the Chancellor Prince Alexander Gorchakov in honor of the American delegation in August 1866 at the English Assembly in St Petersburg.

Many recipes have come down to us. "Men’s club zhzhyonka,” “zhzhyonka for St. Petersburg gourmets” and “merchant zhzhyonka” are just a few versions from Ignatius Radetzky, a symbol of fine metropolitan cuisine of the mid-19th century. One recipe was made from champagne, rum (2 bottles), Sauternes (1 bottle) and pineapple, but in the "merchant" version Sauternes was replaced by just a glass of cognac. The gourmets in St. Petersburg preferred champagne — but only Veuve Clicquot — together with kirschwasser and white rum.

Russian epicures loved zhzhyonka. M. L. Dubois-Uvarova found six ways to make it. These were mainly combinations of various kinds of alcohol, from Hungarian wine to rum and sherry along with spices and aromatics — cinnamon, orange peel, cloves, lemon. And, of course, the obligatory series of exploits involving wine and fire.

A 1909 book by Sofia Dragomirova (the wife of General Mikhail Dragomirov), "An Aid to Housewives,” gives a much simpler recipe:

"Pour two bottles of champagne into a saucepan, add chopped pineapple, 1 pound of sugar in small pieces, a glass of rum, and a glass of good brandy. When it comes to a boil remove from the stove, put a lump of sugar on iron mesh, pour rum over it, light it, and continue pouring rum as desired, so the zhzhyonka is hot."

Alas, the time when hussars bathed their horses in champagne has come to an end, along with it the era of zhzhyonka in Russian culture. In the Soviet cuisine zhzhyonka is more often the name of a syrup made from burnt sugar that was used to improve the taste and color of candies and gingerbread.

However, at Christmas and New Year's Eve there is nothing stopping you from playing with fire and trying some old-fashioned burnt punch. Your guests will be thrilled.

Russian Burnt Punch

Ingredients

- Lump sugar: 1 ½ to 2 pounds

- Champagne: 2 bottles

- Cognac - 1 glass (4/5 c)

- Muscat wine - 1 glass (4/5 c)

- Dry white wine: 2 glasses (1 ¾ c)

- Spices: 5-6 cinnamon sticks, 10 pieces of star anise, 10 cloves, 10 cardamom pods. (Quantities can be varied according to taste.)

- Fruit: orange, lemon, pineapple to taste.

Instructions

- Pour all the alcohol except for the brandy into a 4-5 quart stainless steel or tinned copper saucepan. Place on the stove and bring to a temperature of 70-75 degrees C. When you start to heat it up, place a rack (preferably like a grate) over the top of the pan.

- Place a whole lump of sugar (or position cubes) on the rack. The sugar absorbs the rising fumes from the wine. When the wine is hot, take the pan off the stove, pour the brandy over the sugar and light it. The sugar will burn, melt and drip into the wine. When the sugar has completely burned off, stir the drink with a spoon and pour into glasses. Serve hot.

- Adjust the strength of the drink by adding a little brandy or white wine, preferably sweet Muscat wines.

- For anyone unused to strong liquor, add pieces of fresh pineapple, orange or peach to the alcohol as it heats.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.