Thursday was a special day in the Soviet Union— Fish Day. All the cafeterias in the country only sold fish dishes that day. Until Friday dawned, meat and poultry were off the menus and Soviet citizens dined on fried pollock or minced cod patties.

Fish Day was invented by Anastas Mikoyan in 1932. The order of the People's Commissariat for Supply of the USSR "On the introduction of Fish Day at public catering enterprises” was his idea. Why he came up with the idea was no mystery. On the one hand, the country was experiencing a shortage of meat. On the other hand, the government planned to further develop the fish and canning industry. And most importantly, the food commissars wanted to encourage the people to develop new tastes that would contribute to a more diverse and healthy diet. In these same years they introduced new types of cereals, canned foods and ready-to-cook foods.

Now once a week the Soviet people had to eat fish.

A little later in 1939 Polina Zhemchuzhina, the Fish Industry Commissar, worked to diversify the culinary choices on Fish Day. The wife of another close associate of Stalin, Commissar of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov, Zhenchuzhina had headed the perfume factory Novaya Zarya and then became the head of the entire perfume industry in the U.S.S.R. and Deputy People's Commissar of the Food Industry. But in early 1939 she received an unexpected proposal to head the newly created Commissariat of the Fish Industry.

She took her new job seriously and accomplished a great deal. At her insistence the fishing fleet was separated from the merchant fleet and began to operate by its own rules. Zhemchuzhina realized that the whole process had to become a well-oiled production chain: fish had to be caught, processed, and sent to Moscow in refrigerated containers. Buying refrigeration trucks abroad even caused her to quarrel with another Stalinist minister, Lazar Kaganovich. He had planned to spend the currency on equipment for the Moscow subway.

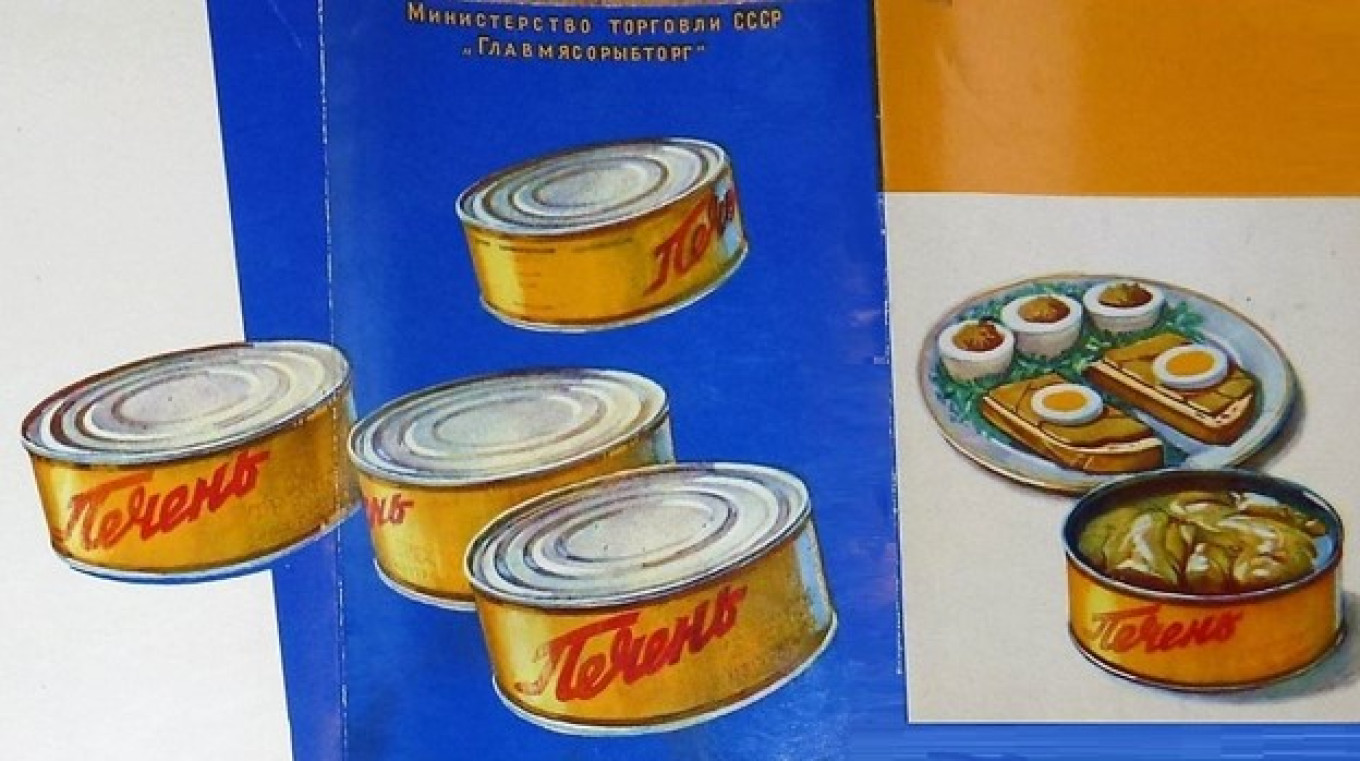

Zhemchuzhina had decided that the canned goods would solve the country’s food shortages. And she was convinced that fish needed to be canned near the place where they were caught. So a huge canning industry was built up in Murmansk and in the Far East. Fifty-five new varieties of canned fish were produced even before the war. Factories appeared like mushrooms after the rain, and fishermen's settlements expanded exponentially.

That's when recipes were developed that became classics. Even today these recipes are used to produce canned saury, sardines, sprat, and cod liver.

Despite her efforts, at first the Soviet public was not keen on buying fish in tin cans. So the Party leadership came up with a unique — if not to say sneaky — way to encourage fish eating. The story goes that at a Communist Party forum Vyacheslav Molotov revealed the sensational information that a large gang of criminals were smuggling pearls to the West while the Soviet Union did nothing to stop them. Molotov said that the smugglers were hiding pearls in tins of fish and smuggling them abroad. As proof of this, he took out a can opener, opened a can and to the amazement of the audience, took out a pearl necklace.

The demand for canned fish exploded overnight. Many people believed every word of the story, and in just a few days all the cans of fish disappeared from stores throughout the Soviet Union. Whether or not anyone found any pearls is lost in the mists of history…

Unfortunately, Polina Zhemchuzhina's successful fish revolution did not protect her from the fate of many who were “close to the throne.” In 1949 she was arrested and spent four years in prison. The traditional accusation of collaboration with "enemies of the people" came as no surprise to anyone. She was accused by the security agencies obsessed with “cosmopolitanism” and of being “in a criminal relationship with Jewish nationalists for a number of years." Zhemchuzhina had, indeed, been on friendly terms with Golda Meir, the first ambassador of Israel and that country’s future prime minister. At one of the Kremlin receptions, Zhemchuzhina told the ambassador in front of witnesses that she was also "a daughter of the Jewish people" and switched to Yiddish. She was released after Stalin's death, but she was no longer allowed to work in food production or the fishing industry.

Zhemchuzhina's husband was assigned to increasingly less prestigious positions starting in 1956: ambassador to Mongolia, representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna. But ironically, when fresh fish gradually disappeared from Soviet stores in the early 1960s, the situation was saved by the brainchild of Polina Zhemchuzhina — canned fish that Soviet consumers had come to appreciate in the late 1930s.

After the war, the idea of Fish Day was forgotten. But at the end of the 1960s the problem became acute again. The catches were smaller, and then to make things worse in the early 1960s Nikita Khrushchev launched a massive project to build hydroelectric power plants. Their first victims were sturgeons. The Volga was blocked by a cascade of hydroelectric plants and the sturgeon couldn’t jump up the river to spawn. Ever since then, sturgeons are found mainly in the lower Volga — and in vastly decreased numbers.

Alexander Ishkov came up with a solution. He managed the fish industry in different positions under Stalin, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev. Anticipating the "fish crisis," Ishkov asked the government for foreign currency to construct large freezer trawlers in the East Germany. Designed for fishing in the open sea, the vessels began to set out in groups of 15-20 ships to fish for six months or more.

Soon the U.S.S.R. became a world leader in fish and whale catches. Soviet consumers learned new names of species they had never heard of before, like the rattail and the Antarctic marbled perch. These fish might not have tasted as good as burbot and sterlet, but they were better than nothing. Consumers with less means bought pollock. For many years it was tasteless, frozen and refrozen many times. People used it as cat food. Today we we've realized that fresh pollock is a wonderful variety of cod: white, dietetic, and in demand all over the world. But back then it reached the buyer in a miserable state. In addition, ocean fish was poorly treated; sold skin-on, it was bitter when cooked.

So the authorities resorted to a tried and true method. On October 26, 1976 the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union once again decreed the introduction of Fish Day. In usual Soviet style this was not presented as a measure due to shortages but the desire to diversify the diet of the Soviet consumers. This time the fish day was made a permanent day of the week — Thursday.

Why Thursday? The press gave many explanations and statistics to prove that people would be most likely to eat fish on Thursday. But the reality was probably different. Top Communist Party officials were probably trying to confuse religious traditions, the way they invented the “May Day” cake to replace the ideologically unsound Easter cake. Thursday was chosen to shift traditional Orthodox fasting days, which fell on Wednesdays and Fridays. Now people would fast from meat on Thursdays.

This was when Soviet “dinners in a can” reach their apex, especially with a salad of cod liver. By the 1970s and 1980s, canned cod livers were already a delicacy that you couldn’t find in regular stores. If you were lucky, you could get one at work as part of a “holiday basket” order. For many of us, this flavor of childhood takes on a new dimension today.

Cod Liver Salad

Take four cans (4.3 oz each) cod liver, four hard-boiled eggs, and a handful of green onions, chopped. Mash the cooled hard-boiled eggs with a fork until they are crumbly. Open the canned cod liver, drain the oil, transfer the livers to a plate and also mash with a fork. Combine the eggs, livers, chopped green onion. Salt to taste.

This classic treat for a visit with friends of the New Year’s table has a host of variations. You can add green peas, diced boiled potatoes, pickled or marinated cucumbers, or canned white beans. If you wish, you can fill tartlets with the salad or wrap it in thin blinis. Or you can enjoy it the old-fashioned way – on a slice of black Borodinsky bread.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.