Natalia Smirnova, the founder of the Russian-language bookstore Babel in Berlin, has been connected to literature since she started working in publishing in the early 2000s.

After leaving Russia in 2015, she did not expect to return to the literary world. But after the invasion of Ukraine, inspired by a friend who opened a bookstore for Russian speakers in Tel Aviv, Smirnova took a risk and launched her own project, aiming to unite people in the German capital.

Babel’s books will be sold at Artists Against the Kremlin, an upcoming exhibition co-organized by The Moscow Times in Amsterdam.

The Moscow Times asked Smirnova about how Babel has become a social space, the impact of growing censorship in Russia on its operations and what it means to curate a bookstore in exile.

The Moscow Times: How did you come up with the idea to open a Russian-language bookstore?

Natalia Smirnova: I’ve always worked with books — in the 2000s I worked in publishing and I later ran a literary agency. There wasn’t really a specific idea [for the bookstore] at first. It felt like Russian-speaking people in Berlin needed a space and a kind of mediator — and a book is just that, it’s a universal means of communication. Books create a space that draws people in. We didn’t have a clear goal, but we did want to open our doors and offer a meeting point — a place where people could come together. Including those who arrived after 2022 and those who moved to Europe earlier.

MT: Did you expect the bookstore to become so popular after it opened?

NS: Honestly, no — not at all. We were planning to see how things would go during the first six months and decide whether to continue. We didn’t even have a business plan. We had nothing to compare it to — there was no bookstore like it in Berlin and no one really knew how many Russian-speaking people lived in the city who would actually want to buy physical books. But things started happening simultaneously — for instance, [the exiled media outlet] Meduza launched its own publishing house around that time. That’s important because it gives publishers hope — and a way to sell their books. Independent bookstores like ours also play a role by creating spaces where people support each other.

MT: How do you brand yourselves?

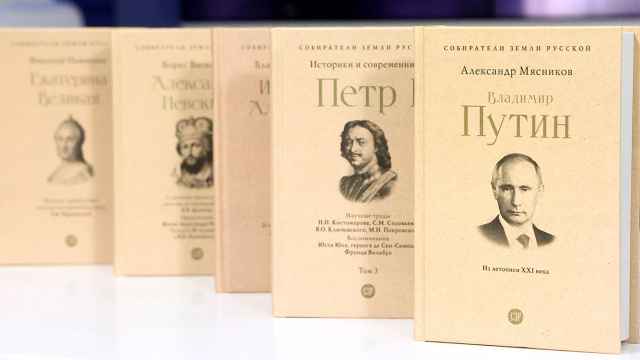

NS: Our audience, of course, isn’t limited to those who came [to Berlin] after February 2022, although they do make up the majority. But we don’t present ourselves as a bookstore built solely around political statements. That said, we and our audience do share a common position — so yes, we did open as an opposition-minded bookstore. Our original selection consisted of books from Russia and most of our books still come from there. We’re not a store that sells only tamizdat, though of course those books are in higher demand and draw more attention.

Still, you can’t build an entire bookstore — even a small one — from tamizdat alone, because there simply aren’t that many titles yet. We don’t choose our stock based on what will sell best. The main principle of our selection is quality books for a discerning readership — people who go to bookstores regularly and buy books. We carry contemporary literary fiction — both originally written in Russian and in translation — as well as non-fiction, particularly in the humanities: philosophy, anthropology, literary theory. We carry titles from small presses too, many of which are hard to find elsewhere. Art and art criticism are also part of our offering. But you won’t find books here by authors who have taken part in Z-propaganda or supported the war [against Ukraine] in any way.

MT: How did the bookstore become a space for events and lectures?

NS: That was part of the idea from the start. At first, we organized more lectures and speaker talks. But we can fit a maximum of 40 people in our space, so it’s too small for speakers with large audiences. That’s why we’ve focused more on book presentations for now. Of course, we don’t limit ourselves to politically focused events or only invite people who can’t speak publicly in Russia, although we’re always happy to host ‘foreign agent’ authors or others who can’t present their work at home. Still, we don’t see ourselves as purely a political or opposition organization. We’re a bookstore, but we’re a bookstore with a clear position.

MT: Do the ongoing bans on certain books and topics in Russia — like LGBT themes — and the raids on publishers affect your selection? If something is banned, does it become more interesting for your audience?

NS: Yes and no. Yes, because when the first banned books came out, like ‘Summer in a Pioneer Tie’ (‘Leto v pionerskom galstuke,’ a summer romance between two teenage boys), people came in asking for those titles because they’d made headlines. But people were asking about them even before that. And they sold out fast. We’re allowed to sell them, but we just can’t get new copies.

And — no, because, for example, when [Vladimir] Sorokin’s novel ‘The Heirs’ (‘Nasledie’) was banned it didn’t affect sales at all. When the book was first released, it sold well because it was Sorokin. Whether the book was banned or not didn’t seem to matter. I think many people have stopped paying attention to what’s officially banned in Russia.

MT: How exactly do the bans affect your ability to get the books?

NS: There are a few stages in this process. When a book is officially banned for sale — especially anything related to LGBT topics, drugs or terrorism — it’s pulled from the shelves. Publishers are ordered to withdraw them. At that point, we can no longer get them. Another thing that’s happening is that even without official bans, publishers are becoming cautious. Some titles are voluntarily withdrawn by publishers or bookstores and they just disappear from the market. Or the print run sells out and the book isn’t reprinted, even if demand is high.

So it’s a process coming from different directions. On the one hand, we’re outside of Russia and can sell these books and Russian authorities don’t control us, but if the book no longer exists in Russia, we simply can’t order it. But we believe that books that were and are still being published in Russia remain important for reflection and discussion.

Babel's books will be sold at the second edition of Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition organized by The Moscow Times and All Rights Reversed gallery at De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 15-Sept. 4.

Visit the exhibition website for more information.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.