Anna Narinskaya has worn many hats throughout her career: a curator, a journalist, a documentary filmmaker, a playwright and an activist.

Her exhibition Boxed, which opened in Berlin in May and is designed to travel, uses multimedia to shed light on topics affecting the LGBTQ+ community in Russia.

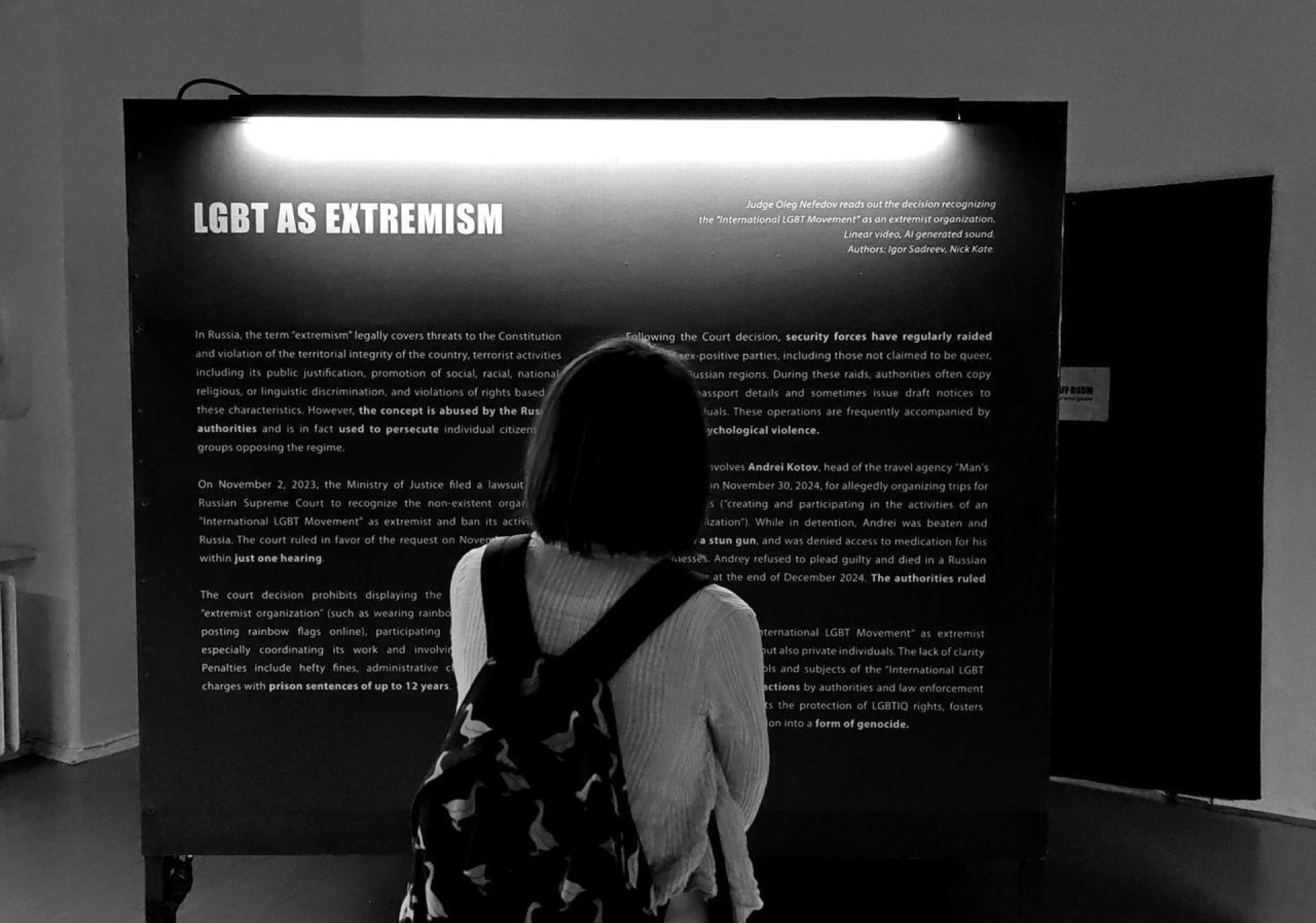

Comprised of seven installations, each existing inside a black box, Boxed explores imprisonment, torture, transgender discrimination, censorship, denunciations, Russia’s ban on the non-existent “international LGBT movement” and the relative openness of the 1990s.

Produced in collaboration with EQUAL PostOst, Boxed will be displayed as part of Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition co-organized by The Moscow Times in Amsterdam from Aug. 15-Sept. 4.

The Moscow Times spoke to Narinskaya about the message she hopes to convey with the exhibition, what people in Europe and the West can take from it and her role in emigration.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Moscow Times: Can you tell us a little about the Boxed exhibition?

AN: It is the second chapter of another exhibition, No Such People Here, which was the first exhibition about LGBTQ+ people in Russia. That one was purely a documentary exhibition based on objects that people took with them when they were rescued from Chechnya. That exhibition had a great impact, which I'm proud of, but that's not the main point. The main point was first to show people the situation and, secondly, to fundraise.

[Boxed] is made up of immersive installations. It uses people to discuss something which is incredibly harsh and horrible. We tried to strike a balance between an amusement park and explaining something really horrible. It was a difficult task for me.

We have the most tragic narratives concerning LGBTQ+ people in Russia: what’s happening to them in prison, how Russian laws work against them, an entire installation about demonstrations. It’s a documentary installation based on the generalizations and reports from gay people in Russia. We gathered everything with the help of stringers in Russia.

MT: And so you view [Boxed] as a kind of an evolution of the first exhibition? Do you view them as connected, or only connected in the sense that they're both about LGBTQ+ people?

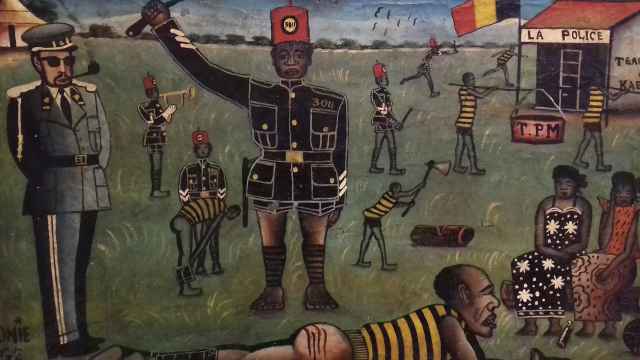

AN: They are somehow connected. For example, there is one installation that was also in [No Such People Here]. It is dedicated to torture. We actually took pictures of peaceful, normal objects. Objects like a plastic package or a meat tenderizer. These objects become instruments of torture in Chechnya. Actually, not just in Chechnya, but in any kind of totalitarian community. We even have a pillow, because there was a tragic story about a young girl who was killed with a pillow by her parents when they found out that she was a lesbian.

At first glance, all these photographs are deliberately taken in a glam way, like an ad. But then you read the narrative and you understand that they're instruments of torture, even instruments of killing.

MT: What was the reaction in Germany?

AN: There are two major types of reaction. The first one was like, ‘Oh, it’s like that, but we are not surprised about anything that’s going on in Russia.’ Because, to them, Russia is this gray or now black territory.

The other one was more, ‘Okay, we didn't know all the details,’ and people praised me on my findings. They were either taken aback or impressed by the facts — or they didn’t believe me, and asked, ‘Are you sure you are right? Are you sure you are not exaggerating?’

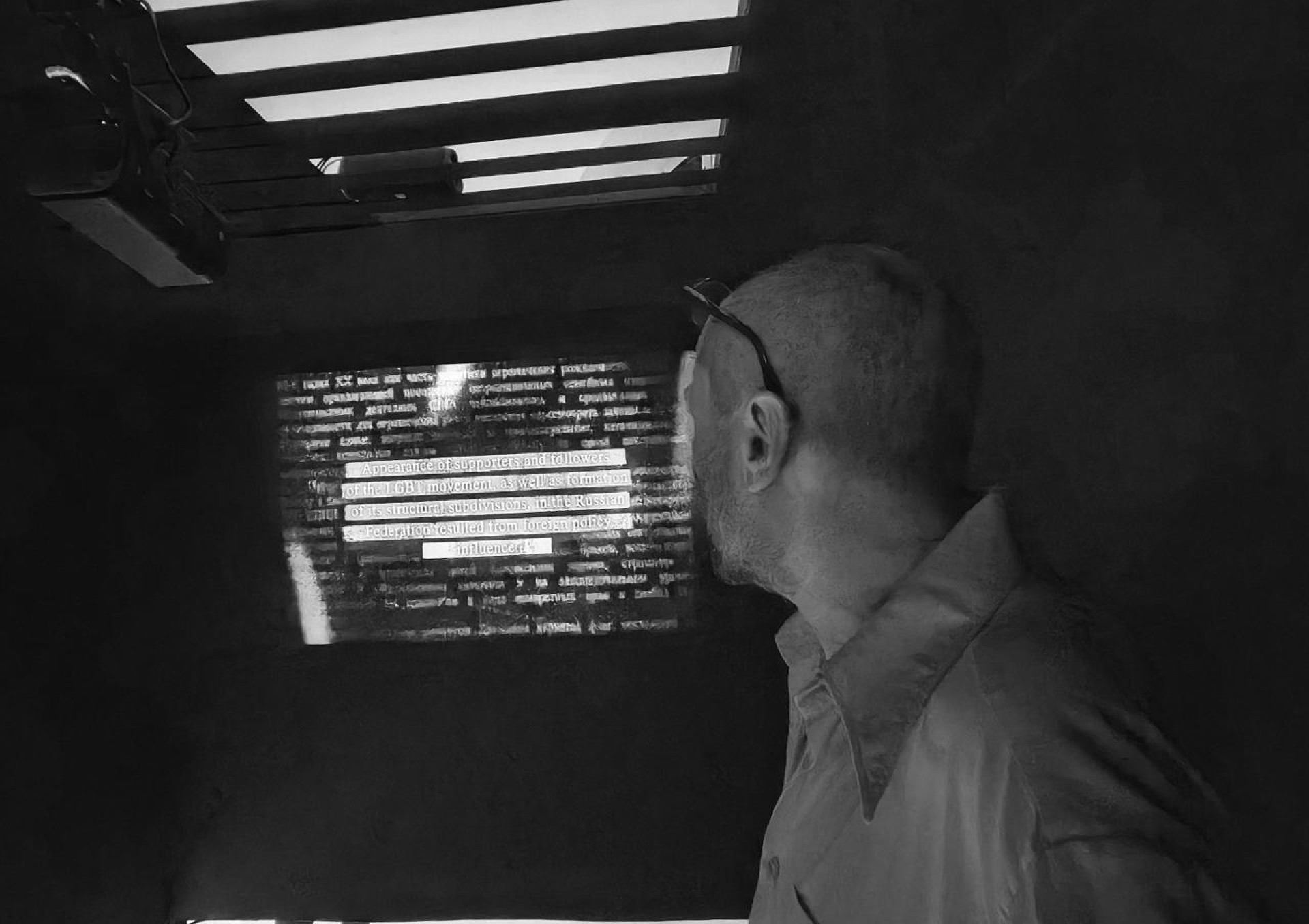

The most striking installation for most people was the one about the extremist designation for the ‘international LGBT movement.’ We projected the court decision onto a wall, like at the beginning of the Star Wars films, and then we used AI to generate the judge’s voice. It’s very simple, but people really stand and read and don’t believe it, because it’s an absolutely absurd thing.

We also have an installation about transgender rights. In Russia, they have started changing transgender individuals’ passports back to their gender assigned at birth. We interviewed several transgender people who emigrated on camera. Many of them are not happy living somewhere else.

Some have been arrested in Russia for trying to buy something with a credit card that has the name of someone who presents a different gender. It's a kind of special torture. [The cashier] understands what's going on, but they call the police and think the card is suspicious.

There was a horrible story about a guy who came out as trans and adopted a child, and the child was taken away from him because of his transition. The child was sick, but they took them to an orphanage because, to the authorities, it's better to be in an orphanage than with a parent who transitioned.

MT: Can Western viewers take something away about their own countries from your exhibition?

AN: I think people in the West are confident, maybe falsely, that it's never going to happen to them. It’s kind of absurd, but in Russia, say, 15 years ago, we were also absolutely sure it was never going to happen. We actually have an installation about how it was in Russia in the 90s, all this television and LGBTQ+ culture everywhere and all the clubs and stuff.

I don’t think that people [here] are critical enough in general. They always think these bad things are happening to others. Maybe there are some people who can understand [it could happen to them], but unfortunately, they cannot really project what's happening onto themselves.

MT: Why did you turn to curation?

AN: Ten years ago, I felt real censorship in Russia, but it was easier to say something in the art world. However, a lot of Russian oligarchs were very much involved in art and they sponsored things. Maybe I should be embarrassed to say I worked with their money, but I almost never worked with state money.

Looking back, one can understand that there's not a big difference between an oligarch's money and state money. Sometimes we had exhibitions in a state museum, so one can say there was some state money. Was it worth doing this? Absolutely. I didn't compromise on anything.

MT: How do you think your role has changed now that you are living in emigration?

AN: Oh, I’m done. I’m lucky because I’m old. Of course, I see people who are really young who are reinventing themselves and doing something [innovative]. I will never be as important, or do as much interesting and influential stuff, as I did back then.

There is also the problem that my expertise is in Russian history and Russian culture. It’s not as in-demand as it used to be. I'm very lucky, I'm doing exhibitions and plays. I'm not complaining, but of course, anti-Putin Russians are in a very difficult situation at the moment. They are canceled in Russia, and they're not really canceled, but they're not really wanted here. You can view it as a part of our collective responsibility, but you're lucky if you come to peace with that.

MT: How has your relationship to Russia changed?

AN: This is the second time I’ve lost my country. I was born in the Soviet Union, it collapsed after I finished university. I was an adult, so I didn't regret it a bit. I have never had this nostalgia. I always thought that there was nothing good in the Soviet Union, absolutely nothing.

But Russia, for me, is divided into two countries. One is Putin's Russia, but of course, I’m not so naive that I think it's only Putin's fault. I do understand how Russia and Putin collaborated on what happened. But I still think that on a private level, intellectual life in Russia was incredibly interestingly organized.

Maybe because we were oppressed, we felt very close to each other: the circle of people who were protesting and doing something which was disliked by the government. It was a very particular feeling of people being close to each other and sharing ideas. I miss that, but it's not like I hope I can repeat it. It was in my life, and maybe one day I’ll write my memoirs.

Boxed will be displayed at the second edition of Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition organized by The Moscow Times and All Rights Reversed gallery at De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 15-Sept. 4.

Visit the exhibition website for more information.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.