In his 1899 classic “Heart of Darkness,” British-Polish novelist Joseph Conrad recounts the tale of a captain who travels up the Congo River in search of a European ivory trader named Kurtz. He discovers the Westerner has, in fact, embarked on a spree of abuse, beating and decapitating native Congolese.

Although a work of fiction, it drew heavily on Conrad’s experiences in the region and was one of the first accounts of colonial atrocities in the Congo Free State (later the Belgian Congo), a giant territory at the heart of Africa claimed by King Leopold II of Belgium in 1885.

Conrad’s novel is notable for exposing the appalling treatment and summary executions meted out to the native population by the colonists. But “Heart of Darkness” nonetheless remains a controversial work in Africa, since it is told from a European perspective that views Africans in simplified, prejudiced terms.

More than a century later, Africa is still fighting for control over the representation of its history and culture. This struggle is made brutally clear by one of the key paintings at a new exhibition of Congolese art at Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art.

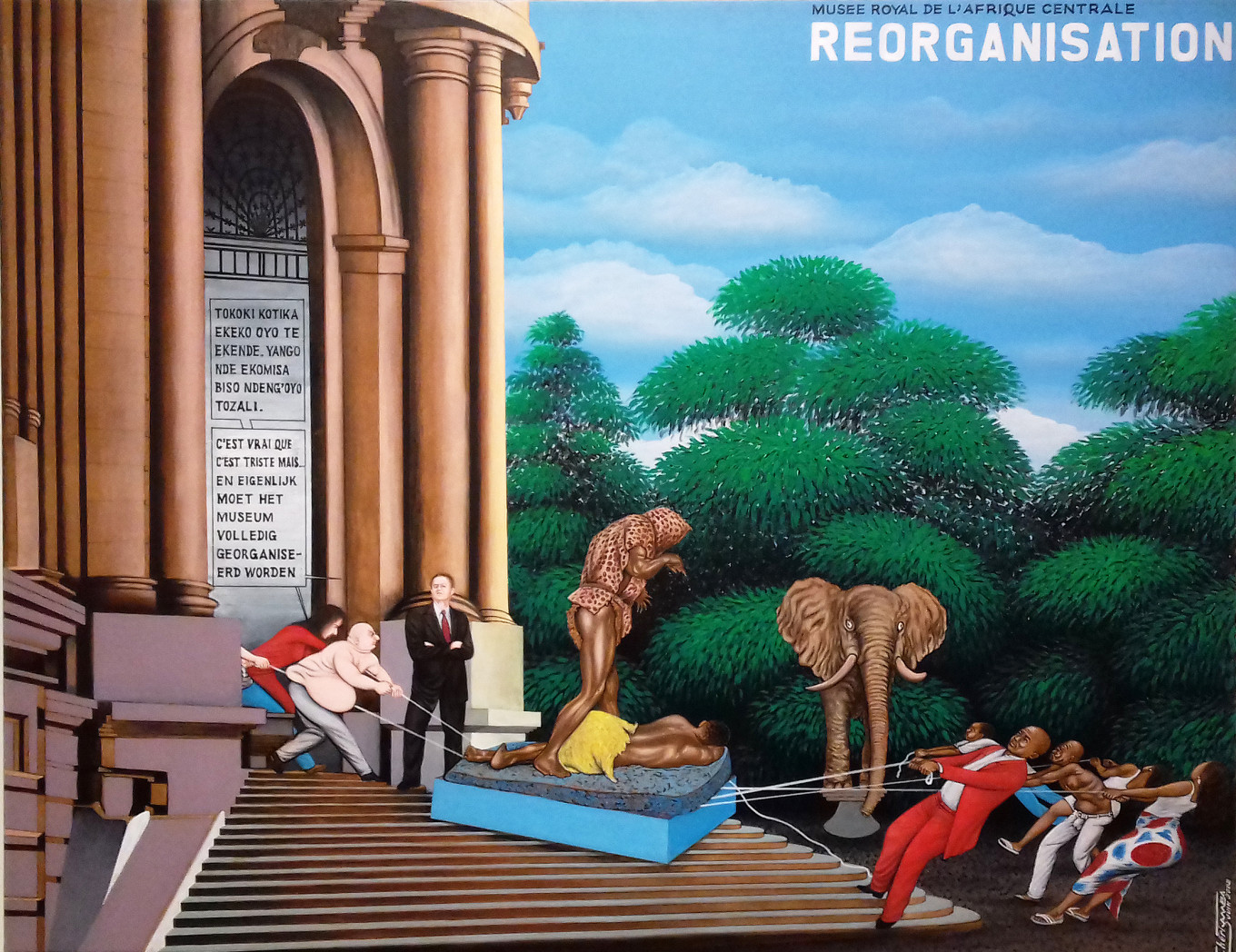

In the painting, titled “Reorganisation,” a violent tug-of-war is taking place on the steps of a museum. The subject of the dispute is a sculpture of a black Congolese, cloaked head to waist in a leopard skin, looming over a sleeping compatriot. A group of Congolese are attempting to pull the sculpture down the steps, while the white museum staff are trying to drag it back into the museum. The museum director looks on, reluctantly sympathetic to the plight of the Congolese.

The canvas, by Congo’s leading artist Cheri Samba, was specially commissioned by the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, to which the colonial sculpture belongs, as a way of reflecting on the conflict over how to represent Congolese history at the museum. The colonial sculpture, titled “The Leopard Man,” is now seen as an ignorant depiction of Congolese “savagery.” Such “leopard men” were in fact political assassins, not devils or bogeymen.

The Belgian Congo’s successor, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), has been independent since 1960. Yet incredibly, it wasn’t until 2002 that the museum – and Belgium in general – began a serious conversation about the abuses of the colonial period and the portrayal of the Belgian Congo and African culture in the West. The catalyst of this process was a 1998 book by Adam Hochschild called “King Leopold’s Ghost.” It focused on the exploitation of the Congo Free State by the Belgian monarch and caused a huge scandal in Belgium on its publication.

Titled “Congo Art Works: Popular Painting,” the Garage exhibition is based on a collection of artworks stored in the Tervuren museum (opened by Leopold in 1897 as a colonial showcase of art and ethnography from Congo), and spans the period from the colonial era to the present.

As Garage organizer Valentin Dyakonov says, the artwork grew out of “very traumatic encounters with the colonial administration” and is predominantly “a reaction to a direct experience of talking and being subject to somebody else’s will.”

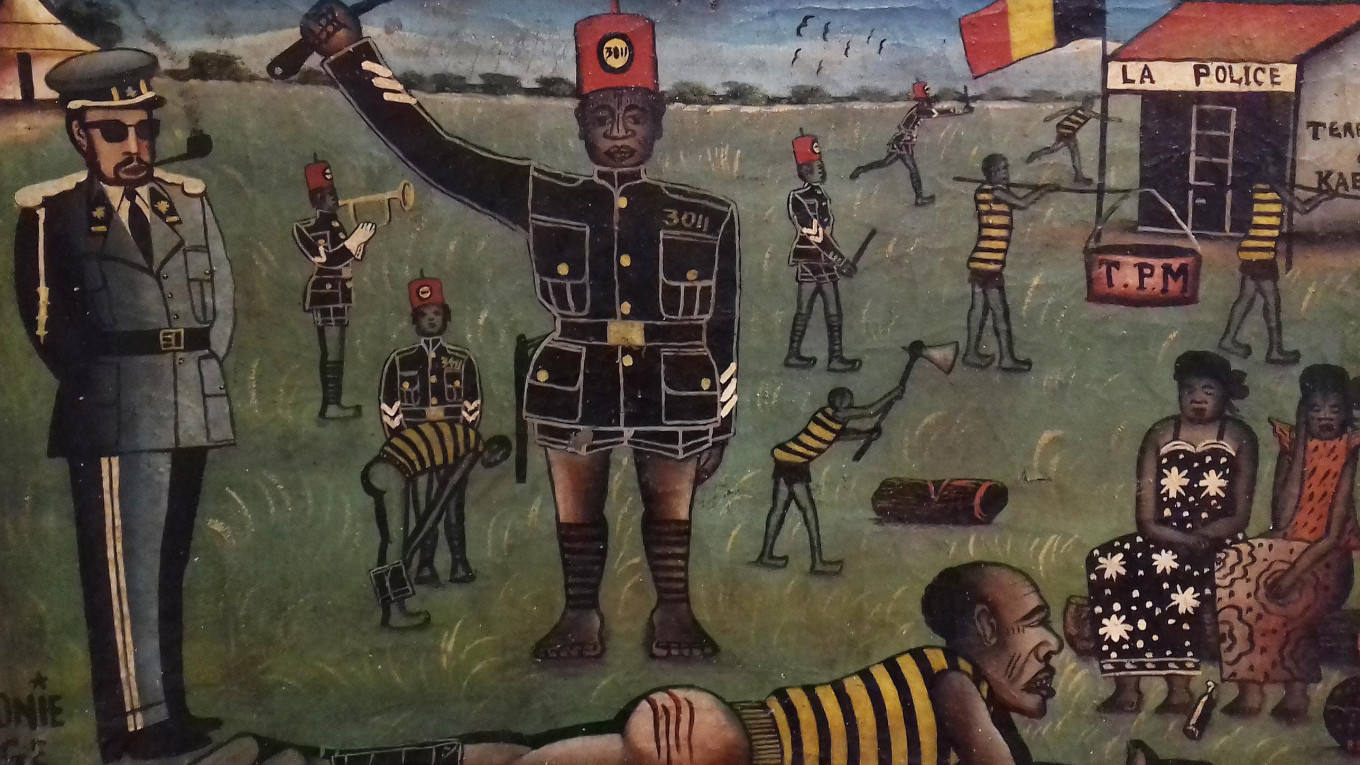

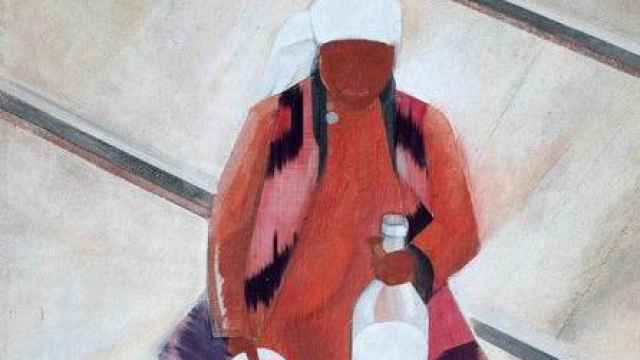

While many of the pictures show animals and birds native to the region, the exhibits clearly show how Congolese artists reacted to the arrival of white Europeans and the accompanying social changes. Their depiction of the new realities shows how they developed an artistic language to deal with colonial rule.

The result is a fascinating collision of foreign subject matter and traditional materials: One artist has fashioned a wooden car with figurines of colonial officials on their way to work; elsewhere, an engraved gourd depicts a uniformed official frog-marching a Congolese with tied wrists. Other drawings show colonists hunting, dining with their families or out walking.

These depictions of the Belgians were not recognized as valuable at the time: Colonial overlords preferred to push artists into producing something more “authentically African.” Some did, however, recognize the pictorial talents of the artists, and hoped they would turn into modernist geniuses.

“In a way they did,” says Dyakonov, “but they were not recognized by the European art world.”

While the paintings from the post-colonial period show scenes from the everyday life of the time – a family boarding a train, a couple dancing in a bar – they also resound with the pain of the nation’s shared suffering under Belgian rule. Dark, violent, and sometimes heartbreaking, the images appear again and again: whippings, beatings, manacles, white priests, uniformed guards, tubby officials, prisons. This is the Congolese artist’s attempt to process trauma, to come to terms with the wounds inflicted on a country.

A whole room is devoted to paintings of the DRC’s first elected president, Patrice Lumumba, who was executed in 1961 (with Belgian involvement) less than a year after taking office. Here he is depicted as a symbol of national awakening, giving speeches as Belgians flock to the airport, or a heroic martyr, beaten and tortured.

Many recent works reveal a sharp political awareness, frustration with the country’s continuing exploitation by the West and anger at corruption. Others celebrate daily life, both in the capital Kinshasa and in rural parts of the DRC. Visually, these paintings are bold pictorial statements that often assimilate speech bubbles and other elements of comic art, and at times even veer into surrealism.

What emerges is a distinctly African artistic voice that is confident and bold in its sensibilities, aims and social relevance. This prompts reflection on the legitimacy of the Western control of the contemporary art narrative and the absurdity of judgements on what is or is not considered to be valid expression.

“I think that contemporary art should be criticized for its total ‘whiteness’ and exclusiveness, and I think that this message of inclusion, this message of an alternative, is one of the questions that people have to ask themselves,” says Dyakonov.

The question is whether local visitors to the exhibition will draw the obvious parallel between what they see here and Russia’s own subjugation of indigenous peoples following the conquest of Siberia and the Caucasus.

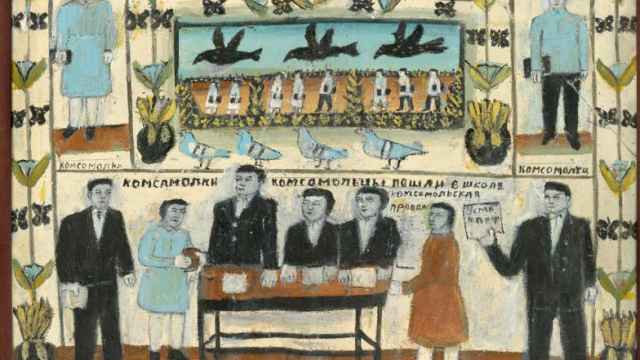

To their credit, the Garage curators have anticipated this and have integrated a display of engraved walrus tusks from the Chukotka region in Russia’s Far East, a kind of "exhibition within an exhibition." The aim is to address the colonial history of Russia, and specifically the Soviet Union, which presented tusk carving as a traditional indigenous practice.

In fact, the Chukotka peoples had only begun to depict scenes on tusks and skins as a form of souvenir trade after making contact with Russian whaling vessels – as the content of many of these scenes makes clear.

“I hope very much that the Russian viewer will ask the same questions that we are asking,” says Dyakonov. If the viewers ask the same questions as we do, I’d be happy.”

As for the fate of “The Leopard Man,” the Tervuren museum is now closed for renovation, but the hope is that when it reopens, this outdated symbol of white man’s ignorance will have finally been consigned to history.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.