For artist Serafima Bresler, the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Soviet Ukraine is a foundational theme throughout her work.

“I do try to move away from [it] sometimes, but I always find myself returning,” the Germany-based Russian artist told The Moscow Times, adding that the temporary occupation of the plant by Russian forces in 2022 made it “relevant again.”

A deeply personal topic for the artist, echoes of Chernobyl will be found throughout Bresler’s works selected for the Artists Against the Kremlin exhibition — though she also found room for one “childlike, playful” piece, as she describes it.

The Moscow Times spoke with Bresler ahead of the exhibition in Amsterdam about the personal inspiration behind her works and what she wishes the viewers would take away from them.

MT: You will be exhibiting three works at Artists Against the Kremlin. Can you talk a bit more about what inspired each one of them?

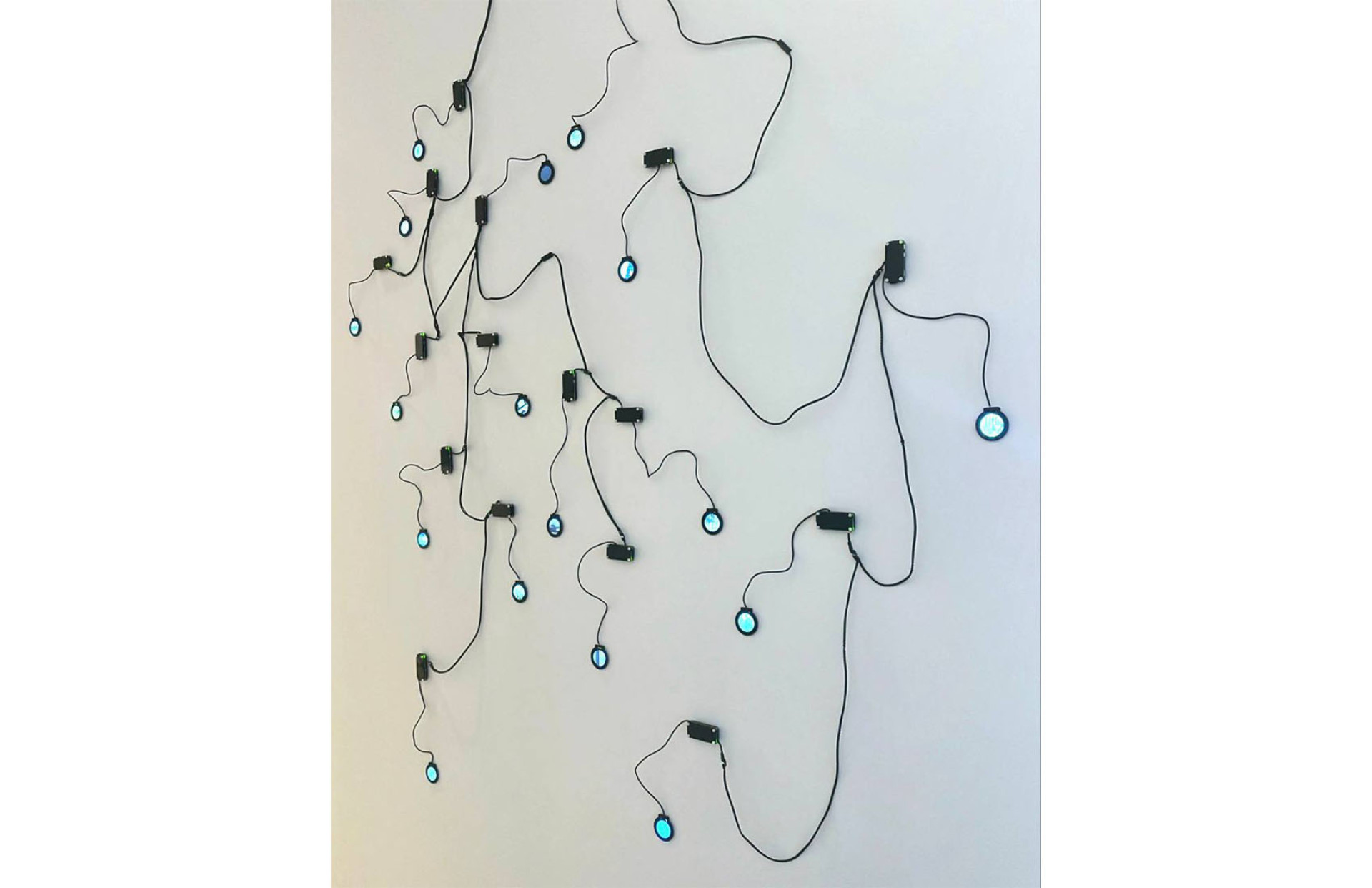

SB: The first work is very important to me right now. It’s a video installation piece called ‘My Trees.’ It consists of microdisplays from old digital clocks and resembles a kind of neural network. The screens are connected with wires and code, and each one displays archival footage.

In this work, I explore two themes: domestic space and catastrophes. I try to reflect on how these two environments intertwine, how catastrophes and their documentation become invisible due to their sheer number and normalization [of violence], and how watching them unfold becomes a kind of everyday norm.

I mix different types of archival footage, including some from my daily life and things like news coverage. [This installation] focuses on current events, specifically the war in Ukraine. But it also spotlights other themes I worked with as an artist and researcher. One of these is Chernobyl, a topic that feels especially relevant now because of [the power plant’s recent] occupation [by the Russian army]. I also included some footage related to the Beslan tragedy, since I’ve created several works on that topic as well.

MT: How did you come to work on the theme of the Chernobyl disaster? Was there a particular personal experience that led you to it?

This topic was a part of my university graduation project at the British Higher School of Art and Design (BHSAD) in Moscow.

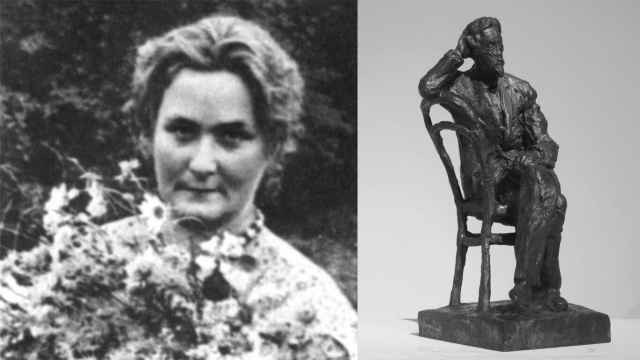

I chose it because of my grandfather, Igor Gerasimov, whom I unfortunately never met. He was a Chernobyl liquidator and one of the lead engineers who had clearance to access the reactor. He volunteered to go to Chernobyl from Moscow and spent three weeks there. He also helped with the aftermath of the [1957] Mayak disaster [in Russia’s Chelyabinsk region].

I ended up creating a small book documenting conversations between my grandmother and me, as well as the stories she recalled. Before that, this part of our family history…was rarely spoken about because of how heavy it is. Maybe [my relatives] wanted to protect me from it — at least that’s what my grandmother told me — and shield me from some of the harder truths.

I gradually expanded into archives and collective memory. I do try to move away from [the topic of Chernobyl] sometimes, but I always find myself returning. It is foundational to my artistic practice.

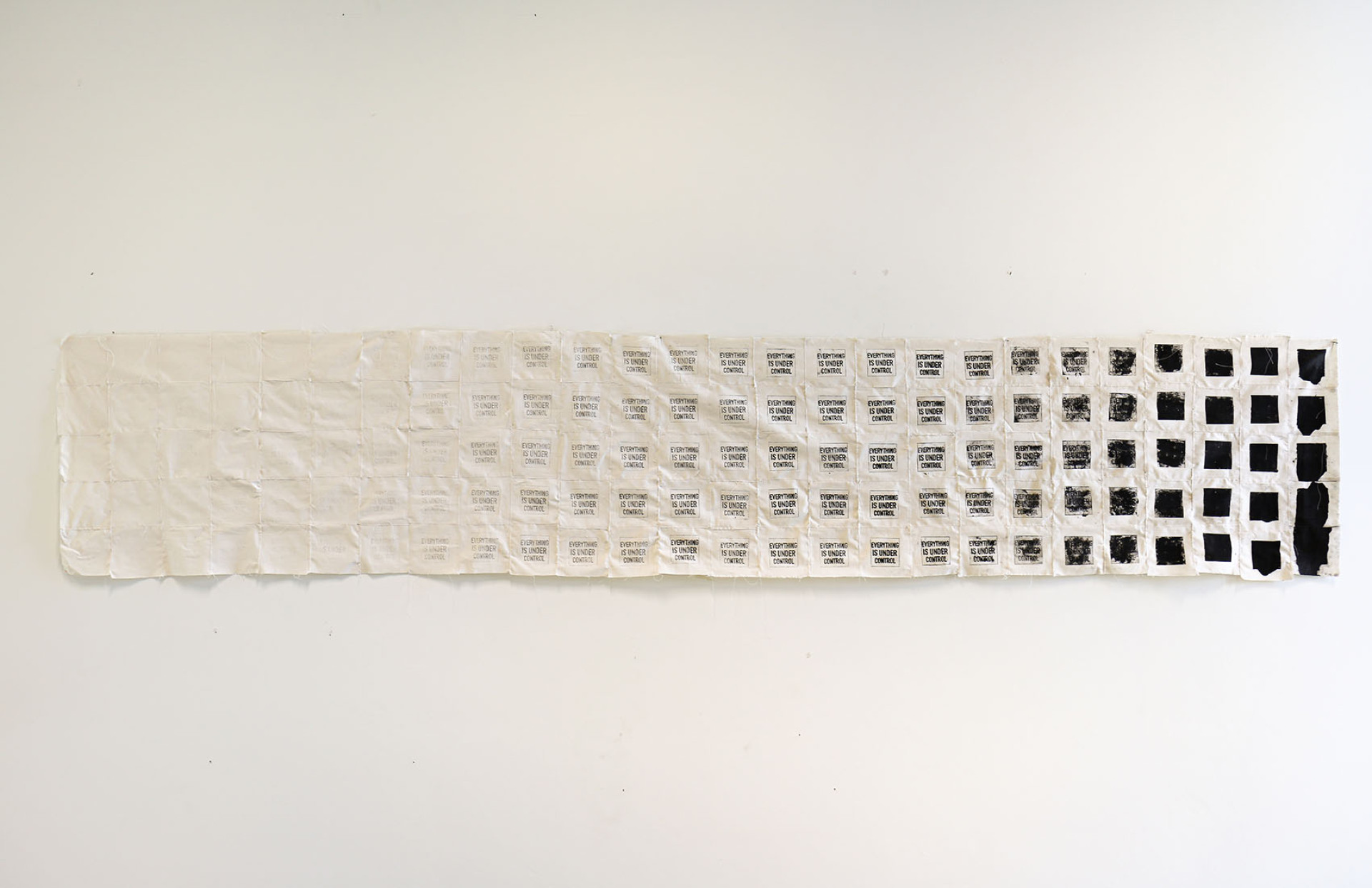

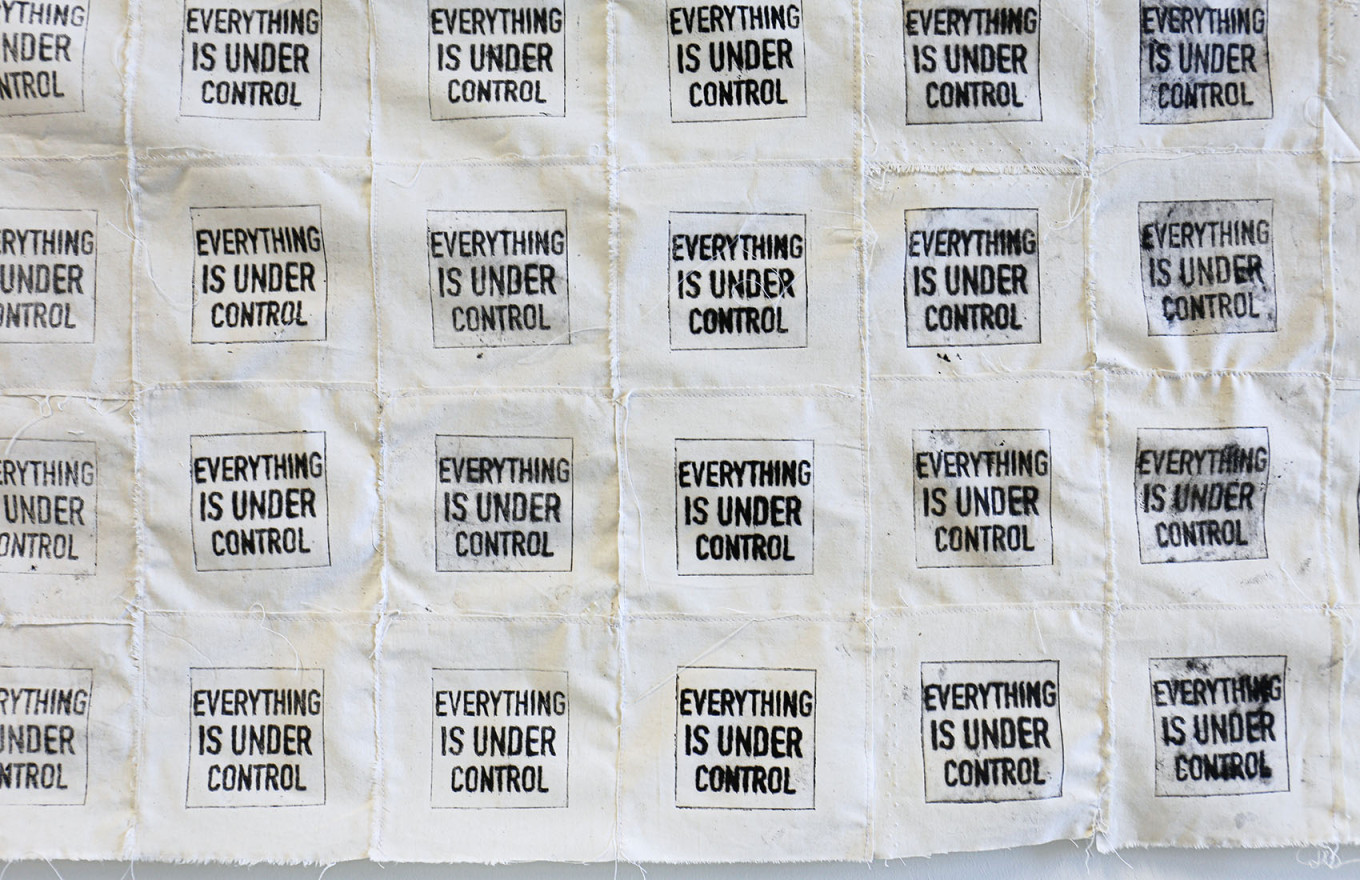

MT: Can you tell me about the piece titled ‘Everything is under control,’ which will also appear at Artists Against the Kremlin? As I understand, it is centered around a statement made by Mikhail Gorbachev…

I dedicated most of my practice to Chernobyl…at some point, this phrase [by Gorbachev] acquired a new meaning and I returned to it once more.

I wanted to make some kind of statement after Feb. 24 [2022], and I simply started printing that phrase. Each square was printed by hand using a drypoint technique. It was somewhat similar to keeping a diary: I printed one square a day, and as a result, the plate I was printing from got worn out. In the end, you can just see the ink — the phrase itself is no longer visible.

This phrase is a symbol of [political] propaganda and lies, which you can hear very often — not only now and not only [in Russia] in regards to the war in Ukraine, but all across the world.

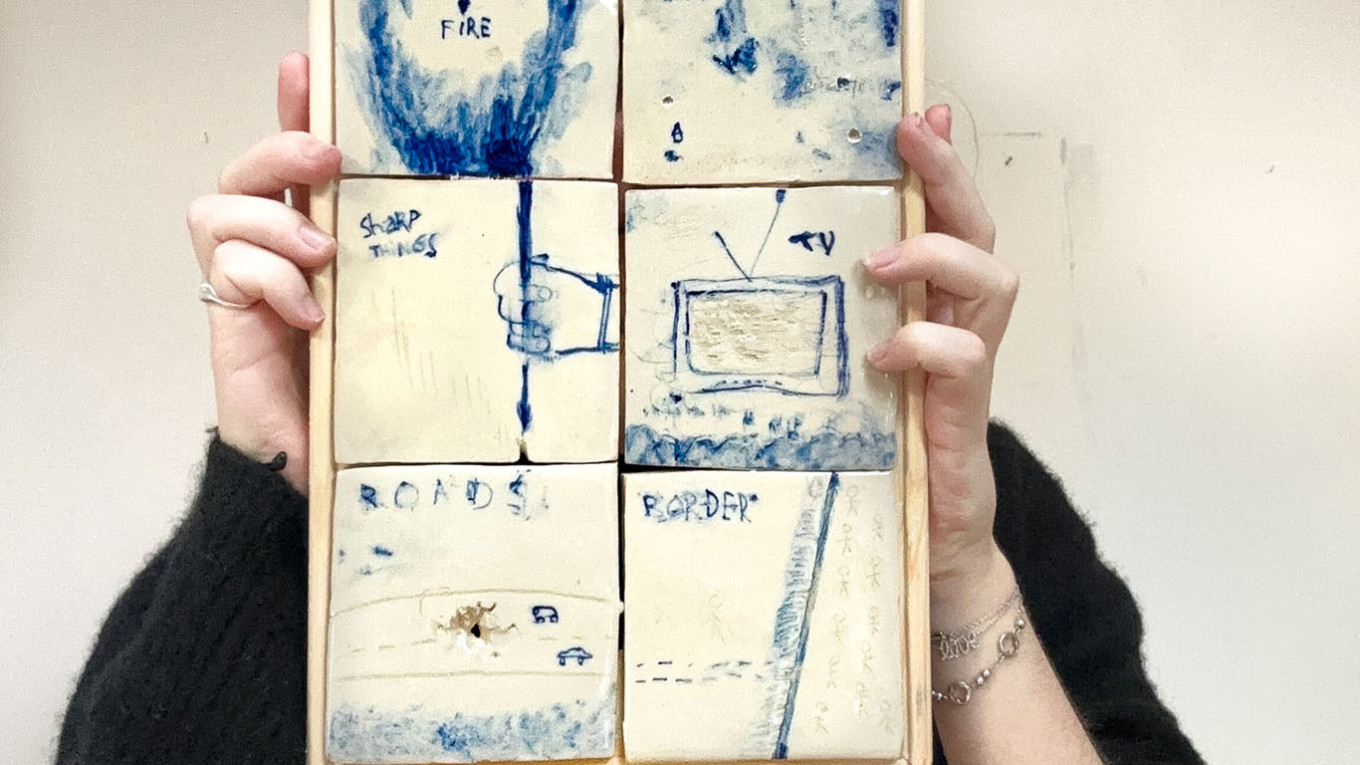

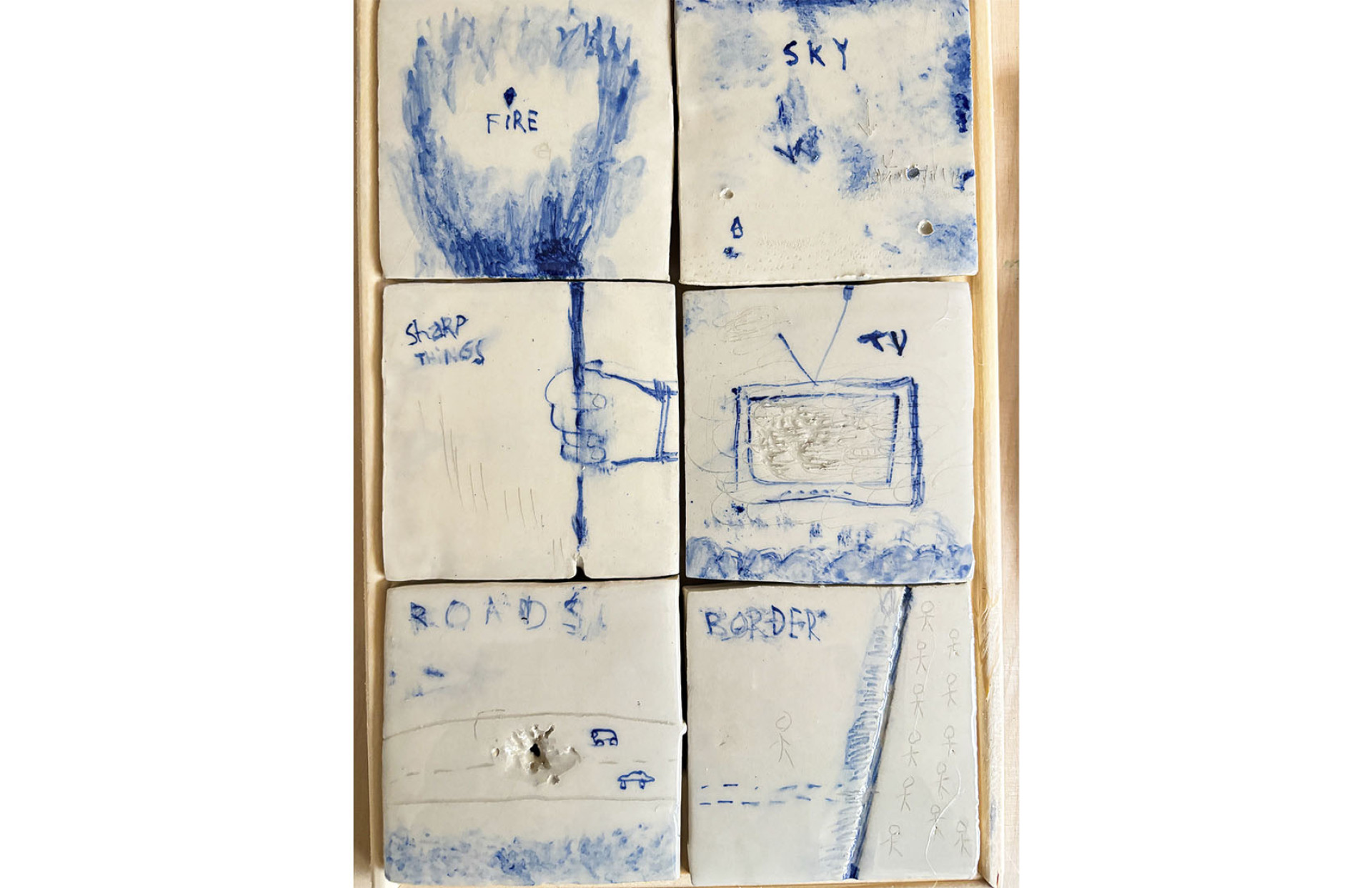

MT: Another work you will be showing is titled ‘This world is beautiful, but…’ These ceramic plates with drawings look quite peculiar. What is the story behind them?

Some of my projects are very large-scale, involving big themes and a large amount of research. This work, however, was done in a more…childlike, playful form.

I made a list of the kinds of things our parents warn us about when they say, ‘Yes, you can go outside, but please be careful with…’ and then started depicting it on ceramics. It was also an experiment in working in a new medium.

MT: What would you want the exhibition audience to take away from your works, especially the ones dedicated to ongoing conflicts?

The audience’s engagement with ‘My Trees’ is very important to me. All the information presented in that work is also present in our phones, and the installation serves as a reminder of what’s going on in the world around us. I truly feel that many people, in a way, have gotten used to the reality we’re living in.

MT: As an artist in exile, are you trying to convey something to the Russian audience, and is it working? As I understand it, your works are exhibited only in the West.

I left Russia before the war…because I wanted to get an education and, perhaps, express myself more freely. I didn’t have to flee the country the way many artists did, especially those who had put on large protest exhibitions.

It just turned out that the art I create took on a protest meaning within the context of Russia, but that wasn’t something intentional. I was simply reflecting on very personal topics through art, my family, not feeling safe in my home country, and so on, but it was perceived as a form of criticism.

As for trying to reach the Russian audience, I don’t think I have a specific message directed at them. Many of the themes I explore might seem no longer relevant or fitting. Even the topic of Chernobyl — I’ve heard several times that people see it as something dealt with and not worth discussing. But it feels important to continue working with it…because it has been talked about far too little.

MT: This exhibition is a reflection on how authoritarian practices modeled after the Kremlin are infecting other countries, similar to a virus. Does this message resonate with you, and how do you relate it to your work?

I think it’s a great theme, and I’m glad that we’ve started to talk about the broader context. Part of the reason I left [Russia] was that I didn’t feel safe in my own country, and now that feeling is returning. Even though I’m still physically safe here in Germany, there’s this sense of complete instability, of external threat, and it does feel similar to a virus spreading.

Serafima Bresler’s art will be displayed at Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition organized by The Moscow Times and All Rights Reversed gallery at De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 15-Sept. 4.

Visit the exhibition website for more information.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.