Ilya Repin is best known as a realist painter, whose portraits of writer Leo Tolstoy and canvases such as “Barge Haulers on the Volga” and “Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks” represented Russia to the world.

But the show “Ilya Repin: Known and Unknown” at the State Tretyakov Gallery invites you to forget all that — or remember and then marvel at the unexpected sides of the artist’s work presented here.

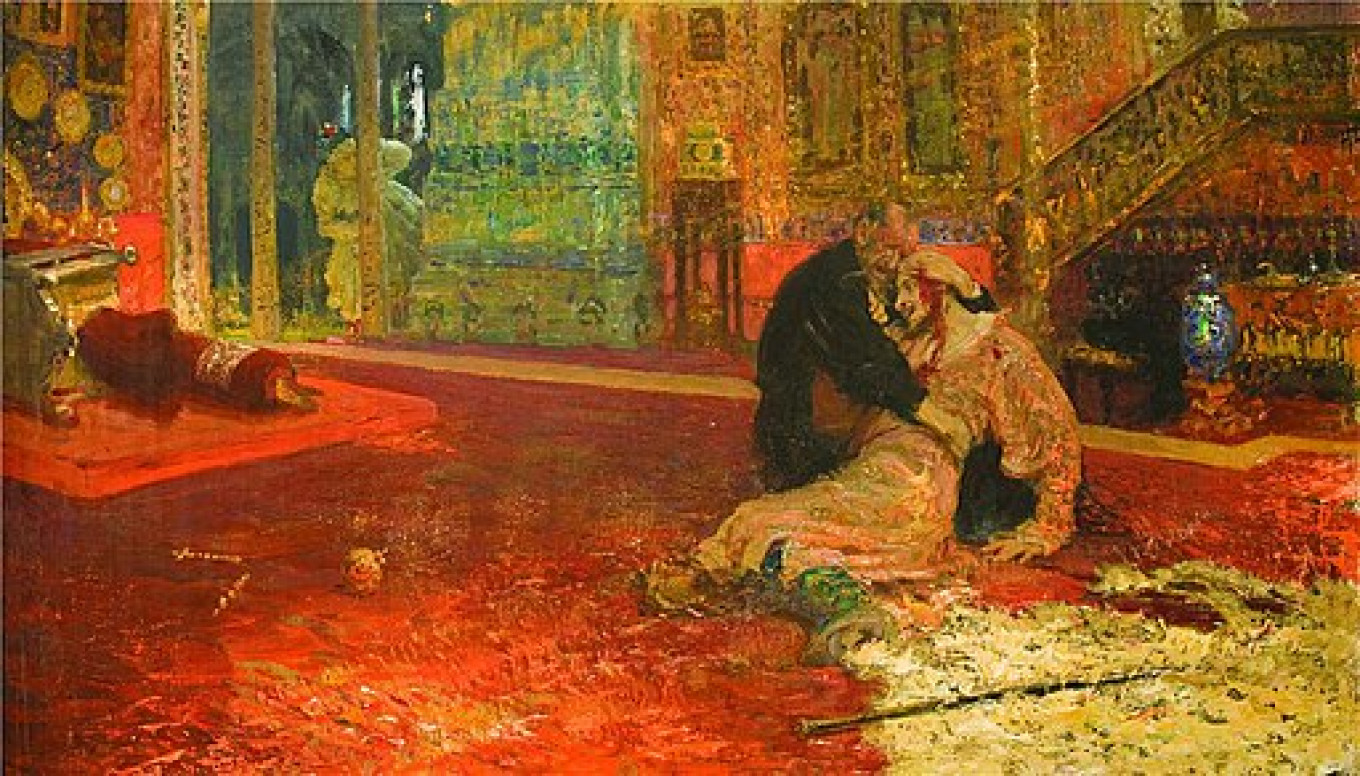

This compact show brings together over 30 pieces combining the lesser-known works from the gallery’s own holdings with those loaned from private collections and rarely, if ever, accessible to the public. It includes a short documentary presenting the torturous history and the currently ongoing restoration work on Repin’s signature “Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581” (1885), which was damaged in 2018 by a visitor to the museum.

Born in 1844 to a middle-class family (his father was a horse-trader, while his mother ran an inn in town), Repin witnessed the Crimean, Caucasian and Turkish Wars; the 1861 emancipation of the serfs; the vast expansion of the Empire; four consecutive tsars; and the 1917 Revolution. After the Revolution, he lived at his estate Penaty in what was then Kuokkala, Finland after its independence from Soviet Russia. He died and was buried there in 1930. Repin’s history, then, is as inextricably linked to the country’s enormous transformations and to the political currents of his lifetime.

The show’s centerpiece is “The Incredulity of St. Thomas,” done in 1921-22. Belonging to Repin’s late emigre period in Finland and a series of Gospel-themed works executed there, the painting’s chaotic density of textures, styles and characters is almost collage-like, as if the master’s old style is here being overtaken by the new in real time. Look closer into the carnivalesque assemblage of faces around the painting’s perimeter and you’ll find echoes of Edvard Munch and James Ensor.

Repin engaged the religious canon throughout his creative life, getting his start in his native town of Chuguev, now Ukraine, with mural work for local churches. He had toyed with impressionism earlier as well, most notably while living in Europe between 1873 and 1876. Yet nowhere is the current of modernism and tendency toward abstraction as prominent within his corpus as in “Incredulity.” Credit it to the times, or perhaps the painter’s self-exile to Finland. Whatever the impetus may have been, it is hard not to read the piece as a cacophonous portrait of the period itself and its inevitable sway over the artist’s picture of the world and of ways to communicate it.

That impressionistic touch as well as a religious reference are also present in a fascinating late remake of Repin’s “Ivan the Terrible” from 1909, also called "Filicide." Gone are the brooding chiaroscuro and the focally wrenching terror of Ivan’s anguished face. The later version is vastly more cinematic, rich with mise-en-scene details and painted with exuberance. A jettisoned rosary and a traditional Christian light beam motif are given a place of prominence. “The disgusting, pathetic, wretched butcher is finally punished,” Repin wrote of the painting, “There is God, there is historical retribution…”

Other traces of modernist and western influence can be seen in the exhibition’s two private collection-sourced portraits, those of Beatrice Levi and Lidia Kuznetsova, the latter especially suggestive of the Vienna Secession.

Repin, the avant-gardist? By the end of the exhibition, that doesn’t sound improbable.

The exhibition will run until February 1, 2022. For more information, see the site.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.