"Something terrible is happening here. Something terrible has already happened."

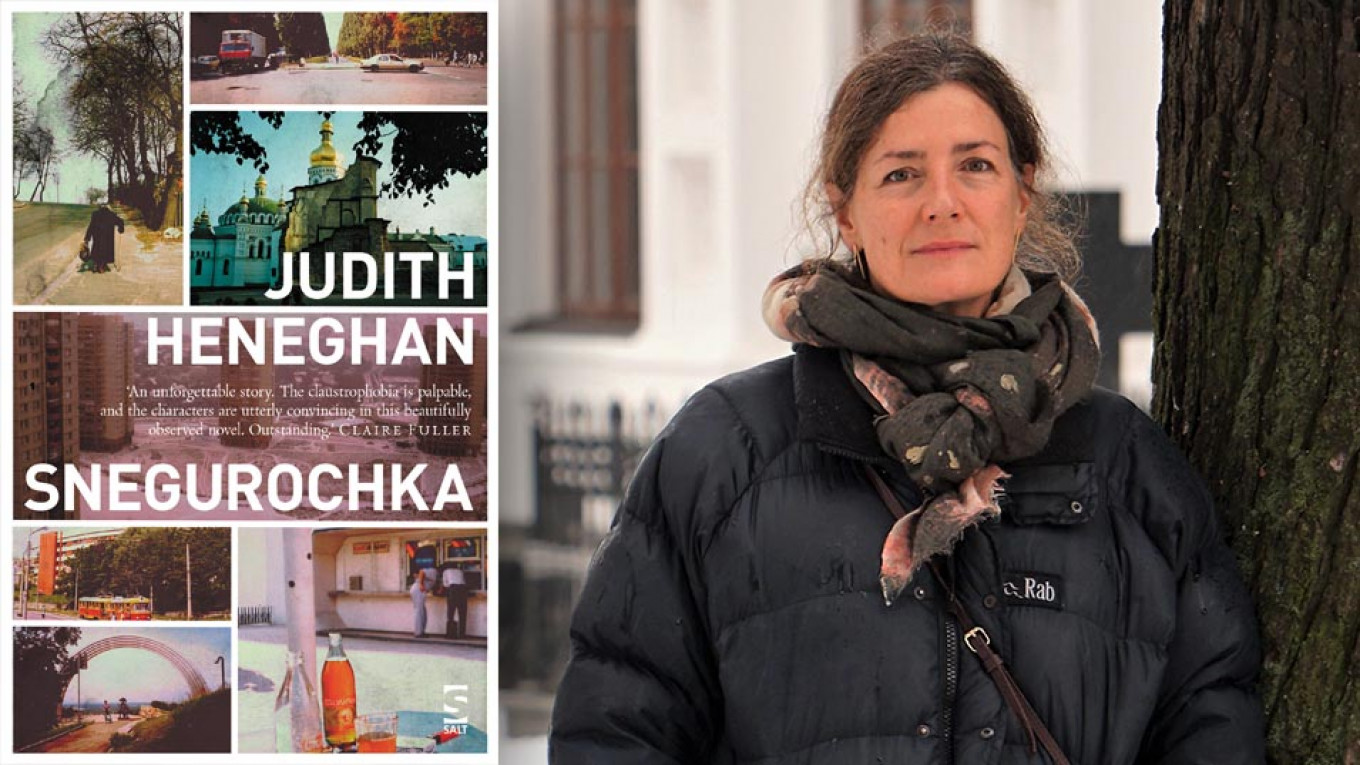

“Snegurochka” follows Rachel, a troubled young English mother who joins her journalist husband on his first foreign posting in the city to Kyiv in 1992 as the country is wracked by uncertainty and upheaval after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Her difficulties expose her to a disturbing endgame between the elderly caretaker of her apartment building and a local racketeer that culminates in a troubling emotional crescendo. We caught up with author Judith Heneghan to ask her about the book, and the powerful themes – both historical and personal – that interweave throughout. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In “Snegurochka” grand historical and political narratives – of Ukraine’s newfound independence, of the Second World War – interweave with the very personal stories of the book’s female protagonists – Rachel, Zoya, and Elena. How do you see the relationship between these two narratives, and was it difficult to maintain a balance among them?

As a non-Russian speaker living with a baby in Kyiv in 1992-4 I spent a lot of time queuing in shops and waiting for trolley buses. Most of the people around me were older, with faces that gave little away. But I knew enough of the country’s past to be curious and sometimes even a little overwhelmed by what the seventy-year old woman in the seat opposite might have witnessed and survived. Rachel, the English mother, cannot ask, but she glimpses some of the consequences that exist outside her frame. I wanted very much to explore the way so much remains hidden to people like me. There is the grand narrative, of course, but as a novelist it felt most natural to probe it at a personal level, where the view is partial and particular, and where the significance is between one person and another.

You lived in Kyiv for several years during the 1990s, the same period in which the book is set. To what extent does the depiction of British expat life reflect your own?

The expat community was very small in the years immediately after independence, and I was quite isolated. We mingled with a handful of other young English-speaking journalists from the U.K., Canada and the U.S., none of them with children; all were smart, humane, and hugely focused on their work. I do remember going along once to the International Women’s Group with my baby, thinking it sounded quite radical, only to find it consisted of charming but surprised diplomats in elegant skirt suits. We met a few World Bank people, a few entrepreneurs and I heard some stories about property disputes and bribes, but journalists were our tribe and we took cheap champanskoye to each other’s flats and frequented the same few gloomy restaurants and basement bars that I’ve tried to depict in the novel.

The descriptions of Ukraine’s capital are so vivid that the city is almost a character in its own right. What about Kyiv inspired you to write this novel – did the idea come to you while you were living there?

Back in 1993 I knew I was experiencing the city from a different perspective to that of my husband, and I wanted to document the way its buildings, its parks, its kiosks and its quiet, domestic corners had taken hold in my imaginative geography. The monastery of Kyiv Pechersk became a particular point of reference. I was frequently scolded, perhaps because of the buggy’s muddy wheels, but its stark beauty and its homeliness drew me inside its walls over and over again. I couldn’t speak the language; all I could do was look, and I made some notes and took photographs to help me remember. I was fascinated, too, by the little orchards and ramshackle cottages of the area we called Tsarskoye Selo. I felt I was walking with ghosts and really this is where the novel began.

“Snegurochka” is packed with symbols, the most potent of which is Kyiv’s Motherland statue which two of the characters can see from their flat. Motherhood in all its forms – sometimes idealized, sometimes tragic – appears to be one of the central themes of the book. Did you envisage the Motherland statue as a symbol of the Soviet state as a kind of mother, albeit one that had a tragic, even cruel, relationship with her children?

The symbolism of the Motherland statue definitely evolved as I drafted the novel. It was never the starting point, but the huge statue is impossible to ignore if you live near the river in Kyiv and you want to write a novel about the act of mothering. I often wondered how ordinary Ukrainians viewed it. It seemed almost to parody its own symbolic self, and yet it moved me. I travelled back to Kyiv with two of my children last year and we visited the military museum built beneath the statue, which now bears vivid witness to the conflict in eastern Ukraine. What might we make of that?

To whom in the book does the title “Snegurochka” refer? In one version of the fairytale, Snegurochka is a child made of snow by two peasants – is the title a metaphor for parent/child relationships?

I didn’t call the novel "Snegurochka" until I’d finished it. But Snegurochka’s origins have long fascinated me and, as with all folk tales, her purpose alters according to our own cultural and social preoccupations. The character Zoya calls Rachel "Snegurochka": the longed-for child, naïve or innocent, yet also the interloper who comes from somewhere else and disappears again when spring comes, or, in one version of the story, when she is not loved enough. Every mother figure in the novel is also somebody’s child, or grandchild. The metaphor is there, and while readers will interpret it as they choose, for me it is about parent/child relationships, yes.

On the one hand, the local racketeer is an archetype of the shady businessmen who emerged in the "wild 90s" after the Soviet Union’s collapse. On the other, his twisted perception of motherhood makes him a very individual character. What inspired you to create this juxtaposition in his character?

The novel needed a racketeer, but I didn’t want him to be a caricature or a flat, two-dimensional version of a "type," so I gave him a fixation I’d observed once or twice in my own Catholic upbringing as well as in Eastern Europe. There seemed to be a certain machismo amongst some men in Kyiv in the early 90s that I think distorted and perhaps fetishized aspects of motherhood, but I hope also that the peeling back of this character’s motivations isn’t entirely unsympathetic. I spent a long time working out how to hint at his conflicted nature on the page. The scene in which he meets Rachel and her son was the first full scene I wrote.

Rachel’s husband is a BBC journalist sent to report on this new and emerging nation (Ukraine) as it begins to define itself apart from Moscow. Other cultural influences are also evident – from Western branded goods to the Latin American telenovela "Simplemente Maria" that she and Elena watch together. Was this intermingling of cultures against the backdrop of nation-building intentional and, if so, what did you intend it to convey?

Yes indeed – the interloper Snegurochka again! But certainly, the control and supply of consumer goods — and Western branded goods in particular — in a period of hyperinflation and the painful transition to a market economy is a theme in the novel. In this respect I was keen to make no distinction between the personal and the political. Specific items from around the world such as TV shows, books, chocolates, cigarettes and washing machines have a literal value as consumables, as well as a symbolic value. I wanted to show how demand creates conflicts of interest in quite ordinary ways for all concerned, though the telenovela also offers what I hope is a joyous common "language" between two characters, Elena and Rachel, who cannot otherwise understand each other. There is, perhaps, a teasing absurdity in some of the items such as Rachel’s copy of “Jurassic Park” and the box of After Eights – an iconic brand of chocolates for British dinner parties of the 1970s and 80s. Meanwhile several Ukrainian characters in the novel are concerned, in different ways, with Ukrainian culture, whether this is the Orthodox church or the land itself or a home-grown journalism rather than the imported variety.

"Snegurochka": Chapter 1

High up on the fourteenth floor, a boy steps onto a balcony. He is twelve, maybe thirteen with slender limbs and shorn hair and he is naked apart from a pair of faded underpants. He scratches the bloom of eczema on his hip as he squints towards the neighboring apartment block. No one is watching him. The steel hulk of the Motherland monument glints from her hillock across the valley, but she is a statue and her eyes are dead.

The boy moves to a pile of junk in the corner and yanks at a rusting bicycle until it breaks free from the chair leg that is jammed between its spokes. The bicycle’s chain has snapped, so he props it against the waist-high wall and hoists himself onto the seat, side-saddle, with one foot on a pedal. Now, perched there with his narrow shoulders hunched forward, one arm hugging the ledge, he waits.

Below him, the air hangs still between the tower blocks and the strand of fractured tarmac that winds down towards the Dnieper. His pale eyes flick across the hazy crenellations of the industrial zone on the horizon. He ignores, to his left, the green and gold canopies of the monastery on the hilltop with those silent, rotting cottages like windfalls at its feet. Instead, lizard-like, he is watching for movement: the cadets playing basketball between crooked hoops on their rectangle of parade ground inside the military academy, the dogs gnawing their rumps in a corner of the car park, and the women spilling out of a tram like spores down on Staronavodnitska Street.

The spores work their way across the waste ground along concrete paths that intersect at sharp angles. Here comes Elena Vasilyevna, the caretaker for Building Number Four. When her dark form disappears between the dump bins far below, the boy shifts on the saddle, leans out and cups his free hand to his mouth. One deep breath, then his jaw juts forward and he makes a sound like a dog’s bark from the back of his throat. For a moment the sound splits the emptiness before it drops down the side of the building. The old woman reappears, her face turning in the wrong direction. The boy smiles, pleased at the effect. Then, just beneath him, he notices something else. The balcony on the floor below is glazed, unlike his own, and the glazing abuts the base of his balcony, which forms a roof. One of the windows is open and the smell of a cigarette rises up towards him. Freshly lit – a Camel.

The boy stands up on the pedal and leans further over the edge. He can’t see in through the glass below because the white sky is reflecting back at him, but a man’s left forearm dangles out through the opening, fingers flicking ash.

Someone has moved in.

He studies the man’s hand. The skin is pale with golden hairs. His shirt is unbuttoned at the wrist – white cotton with thin blue checks. His watch is analogue with a leather strap, not metal. This man is in his twenties, maybe thirty, western, but probably not German or American. He wears a gold wedding band and when the arm withdraws a stream of smoke is blown out into the stillness. The man says something, his voice muffled by the interior. Then a baby starts crying. Its mewls are a new sound, yet within seconds they seem to stake a claim on the building, seeping into the walls, travelling up through the concrete, the steel and the spaces in between. This is the last day of summer. Tonight, the temperature will plummet and people will wake in the morning, sniff the wind and dig out their winter hats. For now, though, the boy remains balanced on the bicycle, a memory of warmth on his skin as the leaves drop silently from the rowans by the tramline, and the air cools, and the Englishman at the window below mutters to himself and lights another cigarette. The foreign journalists say the city is holding its breath, but for Stepan it is one long exhalation.

Excerpted from “Snegurochka” by Judith Heneghan, published by Salt Publishing.

Copyright © Judith Heneghan 2019

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

For more information about Judith Heneghan and her book see her site or her publisher's site.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.