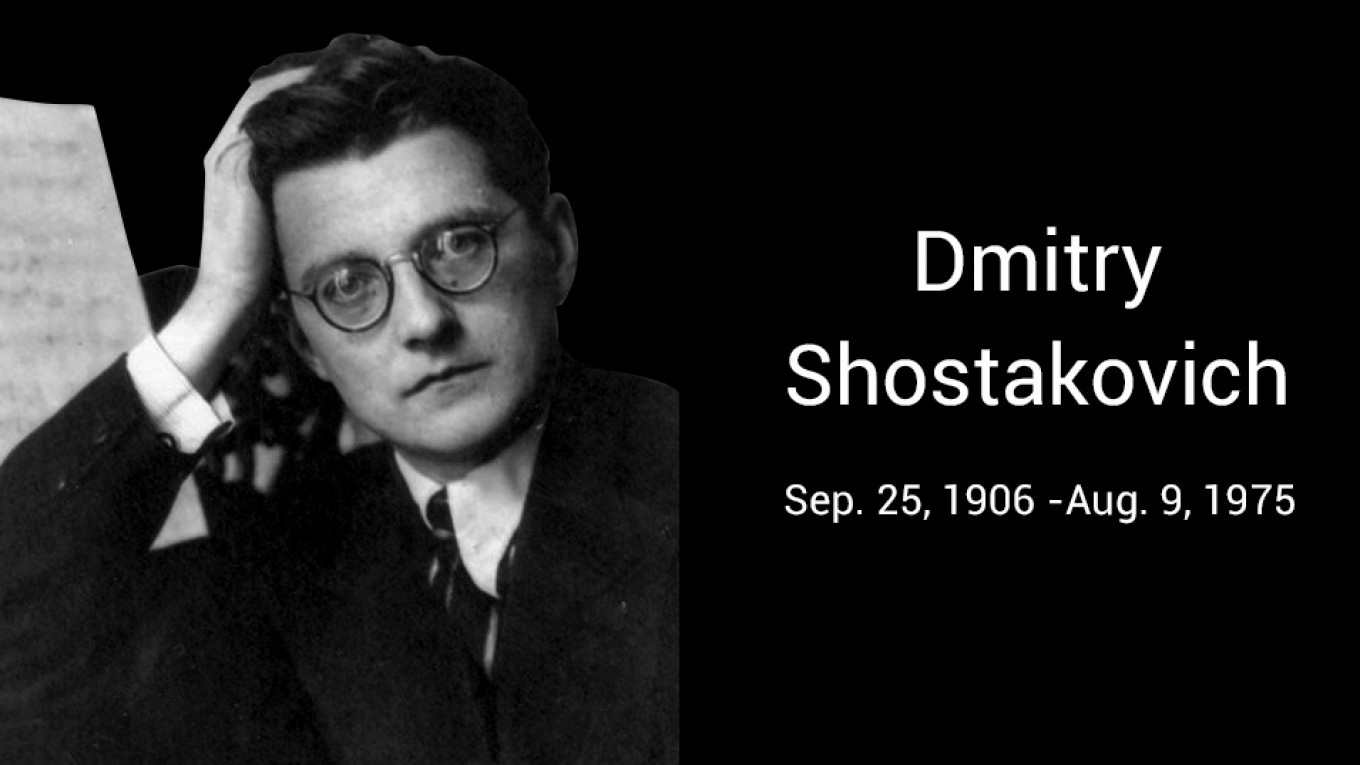

Russian composer and pianist Dmitry Shostakovich was born on Sept. 25, 1906 in St. Petersburg as the second of three children from a Polish Roman Catholic family with roots in Siberia.

He would become known as one of Russia’s greatest 20th-century composers and a tenaciously resilient figure amid the Soviet Union’s crackdown on artists.

Shostakovich’s parents noticed their son’s musical talent as soon as he started taking piano lessons from his mother at age 9. His Symphony No. 1 (1924-1925), released before he was 20, drew worldwide attention to the young composer, and was noted for the wide range of influences it displayed. Shostakovich’s unique musical style was known as polystylism, which saw him weave elements from diverse influences into his compositions.

At the time of his first symphony, the cultural environment in the Soviet Union was still fairly open, and Shostakovich was associated with a proletarian youth theater, which afforded political protection. When he debuted his opera “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” in 1934, it was well-received by critics, despite its decidedly avant-garde style. One reviewer even noted that the opera was the fruit of the policies of the Communist Party.

But two years later in 1936, Stalin attended a performance of “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.” Eyewitnesses said that Shostakovich was "white as a sheet" when he went to take his final bow, and Stalin and his entourage allegedly walked out without speaking to anyone. The next day, the state-run Pravda newspaper published a scathing denunciation of the opera, and Shostakovich had to withdraw from rehearsals of his Mahler-influenced Symphony No. 4.

In 1937, the composer began teaching music composition at the Leningrad Conservatory, and he was living there when the German siege of the city began in 1941. He began composing his Symphony No. 7 (1941) during the siege and finished it in present-day Samara after he and his family were evacuated there. He would eventually return to Leningrad in 1945.

His second denunciation took place in 1948 when Communist Party leader Andrei Zhdanov gave a now-notorious speech attacking the country’s most prominent musicians, including Shostakovich, for their “formalism.” The composer’s works were banned, his privileges withdrawn, and for months he reportedly spent the night on the landing outside his apartment so that his family wouldn’t be disturbed when the secret police came to arrest him.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, Shostakovich was for the most part allowed to work without official interference. The composer died of lung cancer on Aug. 9, 1975 in Moscow, following many years of chronic health problems.

Shostakovich’s posthumous reputation has been complicated, both politically and musically. Publications and testimony from family members, particularly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, have gone far to repudiate accusations that Shostakovich was co-opted by the regime. And although some Western critics find his work derivative, most critics, performers and conductors celebrate his brilliance.

“Amid the conflicting pressures of official requirements, the mass suffering of his fellow countrymen and his personal ideals of humanitarian and public service, he succeeded in forging a musical language of colossal emotional power," musicologist David Fanning wrote in Grove's Dictionary.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.