Writer and comedian Viv Groskop has faced many rooms full of strangers expecting to be amused in her career as a stand-up. But what really scared her in the run-up to the publication of her latest book were the Russians.

“I was terrified they would be offended,” Groskop said. She needn’t have worried.

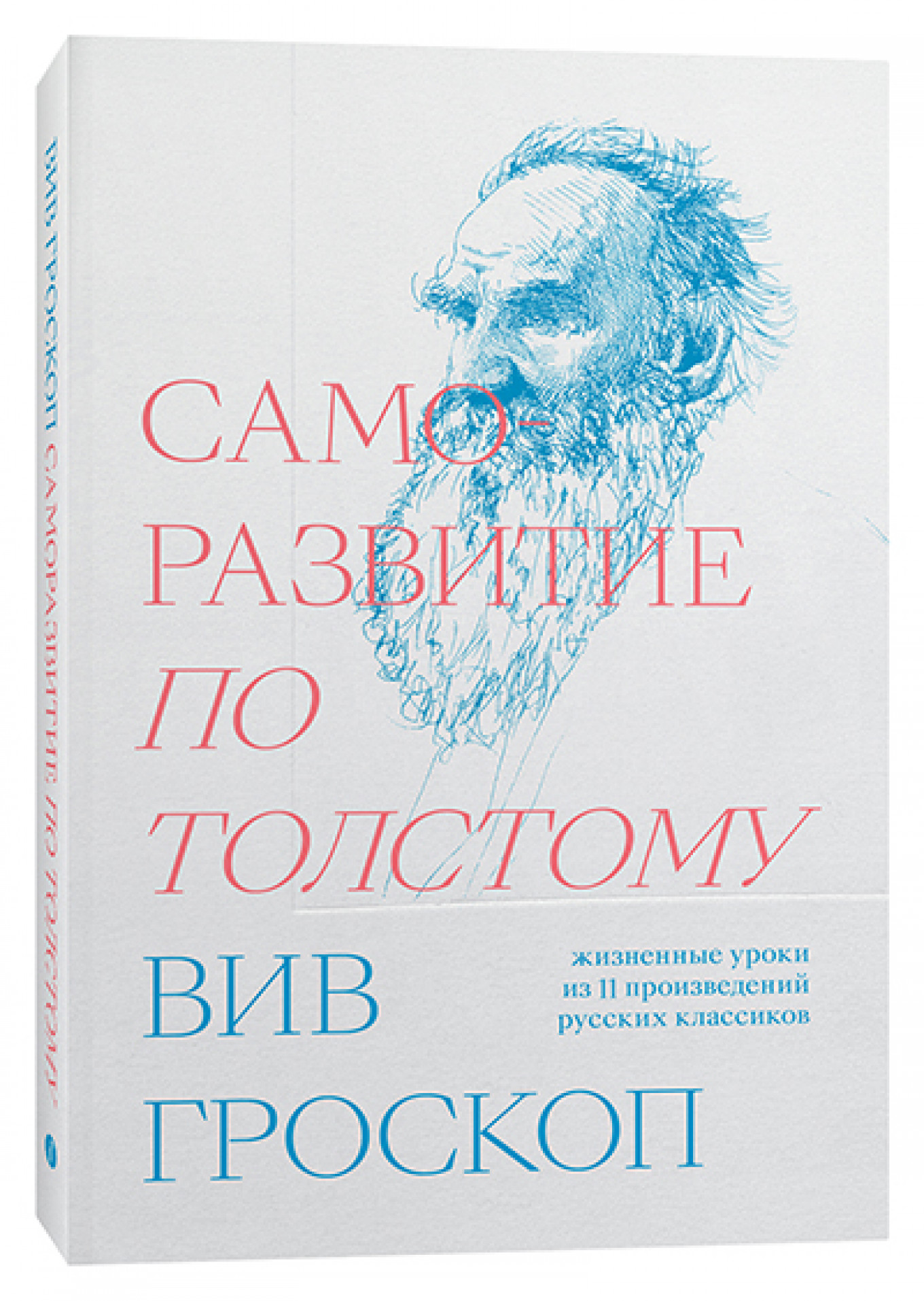

Part memoir, part literary criticism and part self-help guide “The Anna Karenina Fix,” or “Samorazvitiye po Tolstomu” (“Self-improvement Tolstoy-style”), as it is called in Russian translation, dissects the Russian classics with enormous love and respect and pinpoints the lessons that are still relevant today, with a good dose of humour.

The chapter on Anna Karenina is titled “How to Know Who You Really Are (Or: Don’t Throw Yourself Under a Train). Eugene Onegin is How Not to be Your Own Worst Enemy (Or: Don’t kill your best friend in a duel) and War and Peace is How to Know What Matters in Life (Or: Don’t try to kill Napoleon).

There are brilliant quips about the writers themselves too — Tolstoy is described as a “teetotal vegetarian, committed consumer of boiled eggs and serial avoider of pastries,” while Gogol “was the most adorable of all the Russian writers because he was the greediest.”

So far, so funny. But it’s not all laughs. Groskop writes that Anna Karenina represents “the foolish side of Tolstoy that he wishes didn’t exist” and that Onegin’s behavior toward his best friend, Lensky, is “even more offensive and idiotic” than his treatment of his lost true love, Tatyana.

Groskop lived in St. Petersburg in the 1990s, speaks fluent Russian and has written for Russian Vogue. Since its publication in Russian at the end of April “Samorazvitiye po Tolstomu” has gained positive reviews in the Russian media, because every page shouts out that the author adores Russia and knows the country and its people.

Russian Elle called it a brilliant analysis of Russian literature from Pushkin to Bulgakov that shows deep knowledge of Russian culture and notices many new details in famous novels.

The book prompted the government newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta to bewail that Russia buries it’s classics rather than keeping them alive and vital.

“I direct your attention to this book with a little sadness. These kinds of witty and human readings of Russian literature should be published in Russia, as they are in England,” the reviewer said.

That makes Groskop happy because, with political relations between Russia and the U.K. strained in the wake of sanctions and spying and poisoning accusations, she would like to turn the focus to culture.

“I’d like this to be a small, politics-free way of letting people know there are people out there who love Russia,” she said.

Groskop is also a self-confessed self-help guide addict, and she is brutally honest about her own life in the book. The story of her unrequited love for her Ukrainian rock musician boyfriend Bogdan Bogdanovich (which translates as God’s Gift, Son of God’s Gift) is bittersweet. And there are no neat endings in the search for the origins of her unusual surname and her own roots.

At one point she calls Tolstoy “Oprah Winfrey with a beard” and says the writer had an instinct for the sort of thinking that would become hugely popular a century later — teaching that the only way to fight back against the pressures of modern life is to define the right life lessons and apply them to yourself.

It’s this depth and scope in Russian literature that makes the characters universal and the novels so rich that you can revisit them at various points in life and take away a different lesson after each reading, Groskop said.

“I’m not making fun of it, I’m making it fun.”

Viv Groskop’s introduction to the Russian translation of her book

I am excited and honoured that this book is being published in Russia — and in Russian. Although thank God, I have not had to translate it. That would have taken me about thirty seven years and there would have been so many mistakes that you probably wouldn’t be able to understand any of it. I would probably have spelled “Tolstoy” wrong in Russian. I would have got a lot of case endings mixed up. (What is it with you and your case endings?) And I would definitely have mistranslated the mention of samogon. (I know this because I got this wrong in the original first British edition of the book. I always thought “samogon” meant “the fire itself” because it sounds like that’s what it should mean. Of course it means “distilled at home.” This was corrected. But I still think of it as the fire itself. It’s more fun.)

Anyway. This book is the story of my love affair with Russian words and Russian people. This loves burns as bright as the fire itself. I’m thrilled to know that at the very least any Russians who read it will know that somewhere out there are many non-Russians who love Russian literature and culture. In fact we love it so much that our ultimate dream is to be told that we have a Russian soul. Please tell me this if ever we meet.

The only problem with loving something that does not really belong to you is that often, in your blind passion, you misunderstand many things. And I know that Russian readers will frown at parts of this book and think, “What is this crazy Englishwoman thinking of? That is not what Anna Akhmatova was like at all. Why does she have to mention the story about the boiled egg? What does that illustrate about anything?” I will have made mistakes. I will have said some things you may disagree with. I may have completely misinterpreted certain works. But I hope the truth shines through: I have done all this with love. So much love. So forgive me for anything that reads like it was written by a crazy foreigner. (Although, let’s be honest, this entire book was written by a crazy foreigner who thinks that samogon means “the fire itself” and told people this for many years. “Hey, guess what, Russians call home-brewed drink “the fire itself.” Isn’t that cool?”)

I know that the picture I have of “Russian-ness” is in many ways a fictional picture that can exist only in my mind. I have lived in Russia (in Moscow and St Petersburg.) I have learned the language. (But don’t ask me about the prepositional case, please.) I have many Russian friends. I have studied Russian culture for years. But I can never be Russian and I can never access these works in the way a Russian would. This, for me, is the whole point of The Anna Karenina Fix: it’s a window into an outsider’s vision of Russian culture. If anything, this speaks to the power of this culture. If even I can get this much out of it, as someone who cannot convincingly pronounce the difference between a hard L and a soft L — (what is it with you and your hard and soft Ls?) — then what an extraordinarily rich and magical culture that is.

The reason I wanted to become a writer was to feel less alone as a human being. When we share our stories and our ideas, we become part of something bigger than ourselves. When you read something someone has written and think, “Oh, it’s like that for me too” — suddenly life becomes easier to bear. I hope there will be many moments for Russian readers in this book which collapse the distance between us, emotionally, psychologically and geographically.

This seems especially important to me at this point in history. There is a lot of anger, fear and uncertainty in the world. We often forget that these things are part of the human condition and Tolstoy and Pushkin already wrote about them a long time ago. This book is a reminder that not only are we all closer as people than we might imagine, but we are also closer to the past than we care to remember. The Anna Karenina Fix is a celebration of the universal wisdom of the last three hundred years of Russian culture, a wisdom so profound that it can be grasped even in translation centuries later. And it is a celebration of the idea that when we lose ourselves in a book, we no longer need a nationality — because we become part of a global community of readers. It’s also an opportunity for me to announce publicly that I really like Eskimo ice-cream and if you ever see me, please buy me one. I will eat it with great joy whilst you talk to me about my Russian soul. Thank you for reading.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.