(Bloomberg) — Two months before the Russian presidential election, the country's only independent national pollster, Levada Center, has refused to publish election-related data: Because it has received overseas funding, it's been designated as a "foreign agent" — a status that prevents it from any participation in the electoral process.

But that may be just as well. With no doubt as to who's going to win, the exercise only makes sense as a contest between two candidates — Vladimir Putin and Whatever, a concept that's not easy to reflect in a traditional poll.

Putin doesn't appear to feel any need to campaign. His election website, as perfunctory as if he were running for a municipal council seat, has just gone live, and it doesn't even contain a program or any promises — just some questionable statements on how life in Russia has improved under Putin ("The illegal cutting of trees has practically stopped"; "Russian universities have entered the BRICS Top-50").

The site also reports that it only took a week for the Putin campaign to collect 30 percent more than the 300,000 citizens' signatures necessary to put him on the ballot — an impossible achievement for any other candidate but not for the president: Reports come in from different parts of the country of students being pressed into collecting the signatures and workers told to sign for him at work (the campaign has even rejected the signatures harvested at two factories in Kurgan in the Urals).

Given Putin's obvious confidence that he'll get any result he wants — preferably an overwhelming one but not so close to 100 percent as to be ridiculed — the motivations of the people who are supposedly running against him are interesting material for psychologists.

Pavel Grudinin, the Communist candidate who is not a Communist Party member but a wealthy agricultural entrepreneur, says he's running so that all Russians live like his well-paid workers (so perhaps more as an advertisement for his enterprise than anything else).

Ksenia Sobchak, a TV personality, calls herself the "none-of-the-above candidate," arguing that voting for her is the best way to register frustration with the Kremlin's illiberal way of governing.

Grigory Yavlinsky, an old-school liberal who took part in two of Russia's six previous presidential elections and and whose best result was 7.3 percent in 1996, wrote an emotional op-ed in the anti-Putin Novaya Gazeta, hinting at martyrdom and insisting his goal was to fight for his version of the truth — both about the Putin regime and about the right path for Russia.

All these candidates have been granted access to tightly controlled state-owned and pro-Putin private media and allowed to spout different flavors of anti-Putin rhetoric.

As far as the Kremlin is concerned, they're all fighting Putin's corner against the only threat to his legitimacy — which we can call the Whatever vote, which is part protest and part shrug.

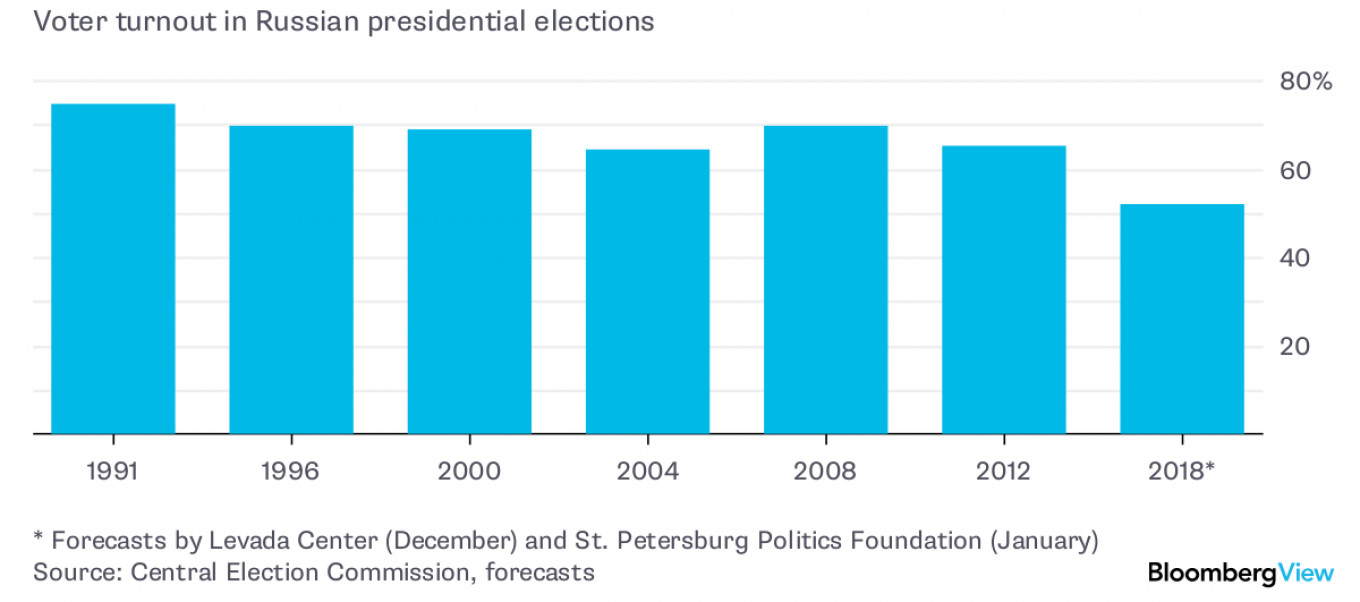

In September 2016, less than 48 percent of Russians turned out for the parliamentary election — a record low result. If something similar happens at the presidential election, Putin will not look like a winner regardless of his result.

There are indications that turnout could be lower than ever. Levada Centre predicted 52 to 54 percent in December, and the St. Petersburg Politics Foundation, a respected independent think tank, came out with a 52 percent forecast earlier this month, putting expected turnout in Moscow and St. Petersburg well below 40 percent.

That would be a disaster for the Kremlin: Even the 2004 election, the most boring in history since not a single political heavyweight dared run against Putin, drew 64.3 percent of registered voters.

Apathy Is A Strong Candidate

Realizing that a turnout embarrassment is the only way to undermine Putin, Alexei Navalny — the only politician who has been running an uncompromising nationwide campaign without access to the media or local officials' cooperation — has decided to side with Whatever.

Navalny was prevented from registering as a candidate because of a trumped-up criminal conviction that's likely to be overturned by the European Court for Human Rights, like the previous convictions of Navalny and his brother, but not in time for the election. So now he's calling for a "voter strike," a boycott of the vote.

Navalny is the only rival Putin appears to take seriously. He steadfastly refuses to mention him by name, and when asked a question about him during a recent meeting with a group of servile editors, he claimed he himself was the preferred candidate of "the U.S. administration and the leadership of other countries" — something of a compliment given Putin's fixation on fighting off a Western threat.

So Navalny's decision to push for a boycott is an important factor for the Kremlin. Its entire machinery is geared toward getting people to come to the polls.

Kremlin officials have been telling local ones to turn election day into a festive occasion with concerts, fairs and sports events. Local administrations have been discouraged from trying to force a higher turnout — it's important for Putin to see real engagement.

There are some novel turnout-stimulating ideas, too. A special version of the popular dating app Mamba will be put out for people to find voting-day partners. The Kremlin is also rolling out a selfie contest.

The goal, according to leaks from Putin's staff, is 70 percent voter participation. State-owned pollster VTsIOM is already reporting that 67 percent of respondents "definitely" plan to vote.

Mathematically, as independent election experts have shown, Navalny's "voter strike" will increase Putin's share of the vote. That, however, will just be a meaningless number.

The turnout figures are the ones to watch. If 52 percent of Russians cast ballots, that's a 52 percent vote for the Putin system in its various guises — and a 48 percent vote for self-reliance or a plague on all of Putin's houses.

That's as close as today's Russia can come to voting for change.

If the abstention percentage, the Whatever vote, is high enough — meaning noticeably higher than in previous elections — what's likely to be Putin's last term in power could turn into a transition to a different future, perhaps even a more liberal one.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.