The withdrawal of Ukrainian troops from Debaltseve removes a major obstacle to the full implementation of the recent Minsk agreement. However, that development also has a different meaning. It was not the Ukrainian side, but their opponents — who are working to dismantle the current Ukrainian state — that determined when the fighting would end.

That is highly symbolic, and not only with regard to this particular conflict. The world has entered a strange phase when the assumptions underlying the recent historical eras are now in question. This includes the idea of the sovereign state, an understanding that emerged from the European Enlightenment and the outcome of the formation of European states after the Peace of Westphalia, a series of peace treaties signed in 1648, which ended a number of European wars.

The bitter feud in Ukraine is only one manifestation of how the world order is falling apart. The Islamic State is an even more striking example. It is not only challenging the established order in the Middle East by erasing borders, but is also exhibiting an increasingly savage cruelty, frightening its opponents with horrific public executions.

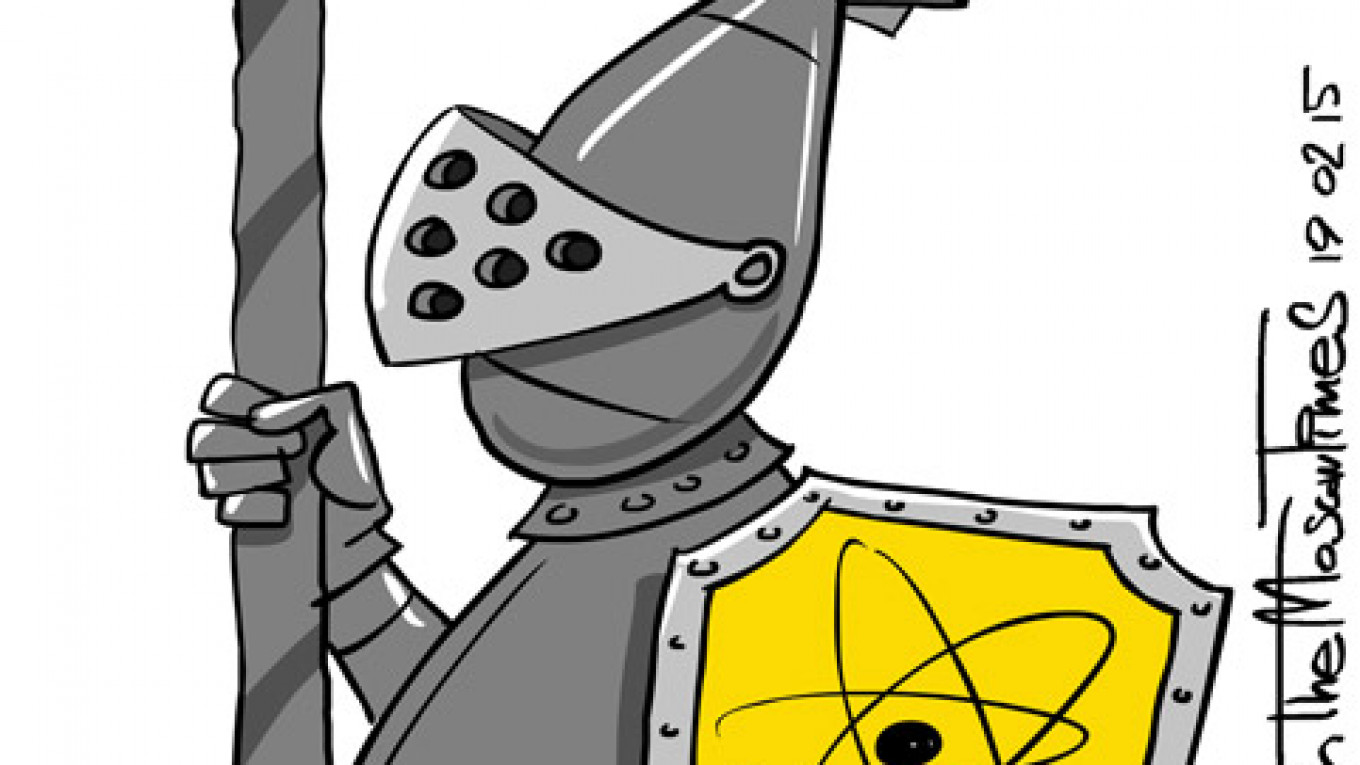

In general, a medieval spirit reigns, with its internecine wars and in which the only great strategy, if one exists at all, is to indulge the passion for blood. This desire to repay the enemy a hundredfold — even if he is yesterday's neighbor or friend — is often mixed with religious fanaticism or blind nationalism.

A little more than 20 years ago, American political scientist Samuel Huntington suggested that a clash of civilizations would inevitably follow the end of the Cold War. Many rejected that grim warning amid the euphoria that prevailed in the West. And although his theory was somewhat overly simplified, it did not succumb to the illusion that mankind had resolved all of its fundamental challenges with the collapse of communism.

Centuries ago, "good Christians" took great pleasure in publicly burning people alive or massacring an entire town in order to eliminate their enemies, just as the Islamic State is doing now. Conflicts motivated by the principle of "an eye for an eye" have almost never stopped during any historical period, regardless of which "civilization" was involved. It is just that, over time, social and political progress created regulations restricting those manifestations of ancestral barbarity.

Why did Huntington and other pessimists of the early 1990s turn out to be right? After all, it was assumed that the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Soviet bloc removed the systemic barriers to extending the most advanced humanitarian and social thinking, the product of the European Enlightenment, to the entire world.

And this is where the major disagreement arose that led to the current situation. In an effort to speed up history, the leading world powers, which, in the late 20th century were exclusively found in the West, began reviewing the key principles on which international relations had been built over the previous 400 years.

This primarily boils down to the principle of the inviolability of state sovereignty and nation-states as the building blocks of the global system. This redefining of the attitude toward national sovereignty had the greatest impact on world events since the 1990s.

The classic understanding of sovereignty has developed from a combination of factors. Among the more objective is the globalization of economics and information that crosses over national borders. Subjective factors include, first, the integration of humanitarian principles into the pursuance of political goals, and, second, the success of European integration.

The consequence of this "humanization" is the concept of the "responsibility to protect" that was adopted at the United Nations level as a moral, rather than legal, imperative. For the first time, it established the possibility of military intervention in the affairs of a sovereign state for moral reasons.

Observers have repeatedly pointed out the failings of that principle given the lack of clearly defined criteria for intervention, and even the impossibility of defining such criteria. However, regardless of the result, it ended up placing the principle of sovereignty in question.

As for European integration, at the beginning of this century that project seemed so successful that it triggered a desire among other countries to attempt the same thing. The EU is not an example of a structure requiring member states to give up their sovereignty, but a serious process by which states forfeit certain privileges in return for greater opportunities.

According to the European ideal, national borders do not disappear, but gradually dissolve in the larger community. They continue to exist, but assume only secondary importance. Everyone understood that unique conditions made that model possible, but the feeling and self-perception of Europe as a standard for others long defined the behavior of the EU and its perception in the world.

However, the fact that Europe has become the personification of political postmodernism has unexpectedly led other places in the world to revert to premodernism.

The sovereign nation-state has ceased to be the de facto determining factor in the system that seems to have emerged after the Cold War, which was considered a sure sign of historical progress. But this rejection of the fundamental element of world order has, of course, shattered the entire model developed during preceding centuries.

Mankind has moved not forward, but toward some unknown condition, and also backward to a pre-Westphalian reality when tribal and religious affiliation determined affairs, and not citizenship in this or that nation-state.

Following a brief, failed attempt to build a postmodernist world, efforts were focused on modernism, but now that has reverted to something reminiscent of the Middle Ages. The most striking examples are the feudal fragmentation of Ukraine and the fanatical frenzy of the Islamic State that carries the fire and sword of the "true faith" without regard to national borders.

At the present tempo of events, this modern-day Thirty Years' War will proceed much more quickly than its historical antecedent, but it will retain the aspect of a multi-level conflict that alternately dies down and flares up again.

The so-called "hybrid war" that observers speak about these days is actually a throwback to the time before the appearance of nation-states. Just as before, the wide diversity of religious, tribal and local geographic identities explains the quirkiness of the means and the ever-changing nature of the goals.

This is clearly not the final destination: history does not end here. Perhaps it will develop in spiral fashion, with renewed consolidation of the state as the only way to protect people from cross-border threats. That is fraught not with hybrid, but with classic interstate wars.

Or, conversely, the state will fail to prove its right to use violence and to collectively represent the interests of citizens who rush to seek protection in new forms of self-organization. Or else that new form of self-determination will lead to what Huntington predicted.

In any case, the post-Cold War era will be remembered as an illustration of the blatant contrast between intentions and expectations on the one hand, and the results of the attempt to translate them into reality on the other.

Fyodor Lukyanov is editor of Russia in Global Affairs.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.