The severe problems in the Russian army go much deeper than the military reforms implemented by Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov. General Vasily Smirnov, deputy head of the General Staff, announced two weeks ago that the fall draft would deliver a little more than 135,000 conscripts. At the same time, however, Smirnov said this number will completely satisfy the army’s current demand, apparently on the grounds that the program to attract professional soldiers will be successful.

Unfortunately, Smirnov, who is responsible for fulfilling the draft quotas, is accustomed to stretching the truth. He has been the point man in the conflict between army generals and the public for 10 years now. Based on his reports, Defense Ministry chiefs announced one year ago that the program for partially shifting the armed forces to contract service had been halted and that the army would henceforth rely primarily on conscripts. In fact, Smirnov had promised to round up as many as 200,000 draft dodgers to make up for the shortage of recruits.

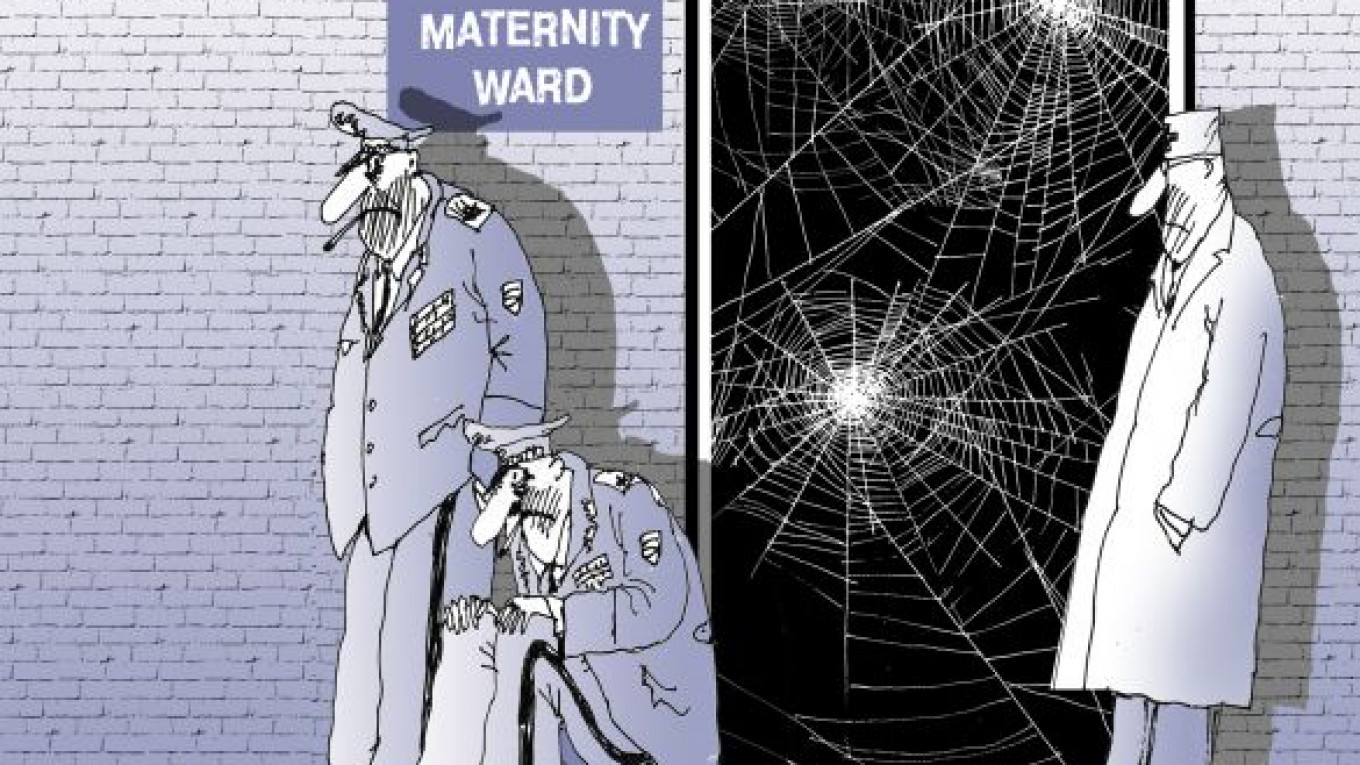

He used the same tricks during the fall 2010 and spring 2011 conscript drives, with army officials trying to press everyone from musicians to dancers into service. Of course, those pretending to have heart problems and other health-related exemptions were among the first on their list. Even illegal Tajik immigrants were reportedly detained and conscripted into service. Draft methods got so out of hand that President Dmitry Medvedev and Serdyukov were forced to publicly rein in overly zealous recruitment officers who were going to extremes to make their conscription numbers.

But even extreme measures did not help. Russia is rapidly falling into a demographic chasm. Scholars at the Gaidar Institute have been warning for the past five years that even if every last draft dodger is put in uniform, the reserves of young men eligible for the draft will be exhausted within two years. And now, it seems, the top brass is waking up to this unpleasant reality that after 300 years the regular army is running out of able — or even unable — bodies to fill the ranks.

Military chiefs continue to insist that Russia should have a million-man army. But under current circumstances, that is a physical impossibility. If the spring call-up is no larger than last year’s, by summer, the Russian army will consist of about 220,000 officers, 180,000 contract personnel, 30,000 to 35,000 military academy cadets and 270,000 conscripted soldiers — a total of roughly 710,000 people.

Claims that large numbers of professional soldiers will sign contracts in the next year are dubious at best. There is no ironclad guarantee that the military will be able to fulfill its obligation to triple officers’ salaries starting in January for the simple reason that there may not be enough money in the federal budget to fund these increases, particularly if oil prices drop significantly below $100 per barrel. Nor is it likely that the army will be able to meet its obligation to raise salaries of professional sergeants and privates to at least 30,000 rubles ($961) per month.

In general, Serdyukov’s goal of recruiting 425,000 contract soldiers by 2017 is largely a response to a bitter interagency rivalry. The Defense Ministry has been decreasing the number of officers to help raise the salaries for the officers that remain. But no sooner had the decision been made to distribute those savings than other siloviki agencies, including the Interior Ministry, Federal Guard Service and Federal Security Service, tried to get a piece of the salary pie. After all, they reasoned, they provide an equally important security function as the army does — only they defend the country from internal enemies, not external ones. And their message got through. Salaries for most members of the army and the Interior Ministry’s troops are expected to be raised in 2012, and the rest of the siloviki’s salaries are scheduled to be raised in 2013.

Russia’s authorities have finally acknowledged that they can maintain an army of no more than 500,000 to 600,000 soldiers. Thus, the shortage amounts to more than 250,000 soldiers. Only recently it was announced that one of the main achievements of Serdyukov’s reforms was bringing all units and troop bodies into a constant state of battle readiness. In reality, that meant using mostly conscripts to fill the ranks in war time. But the difference between the declared level of troops — 1 million — and the real number — closer to 750,000 — means that the armed forces are far from battle ready.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.