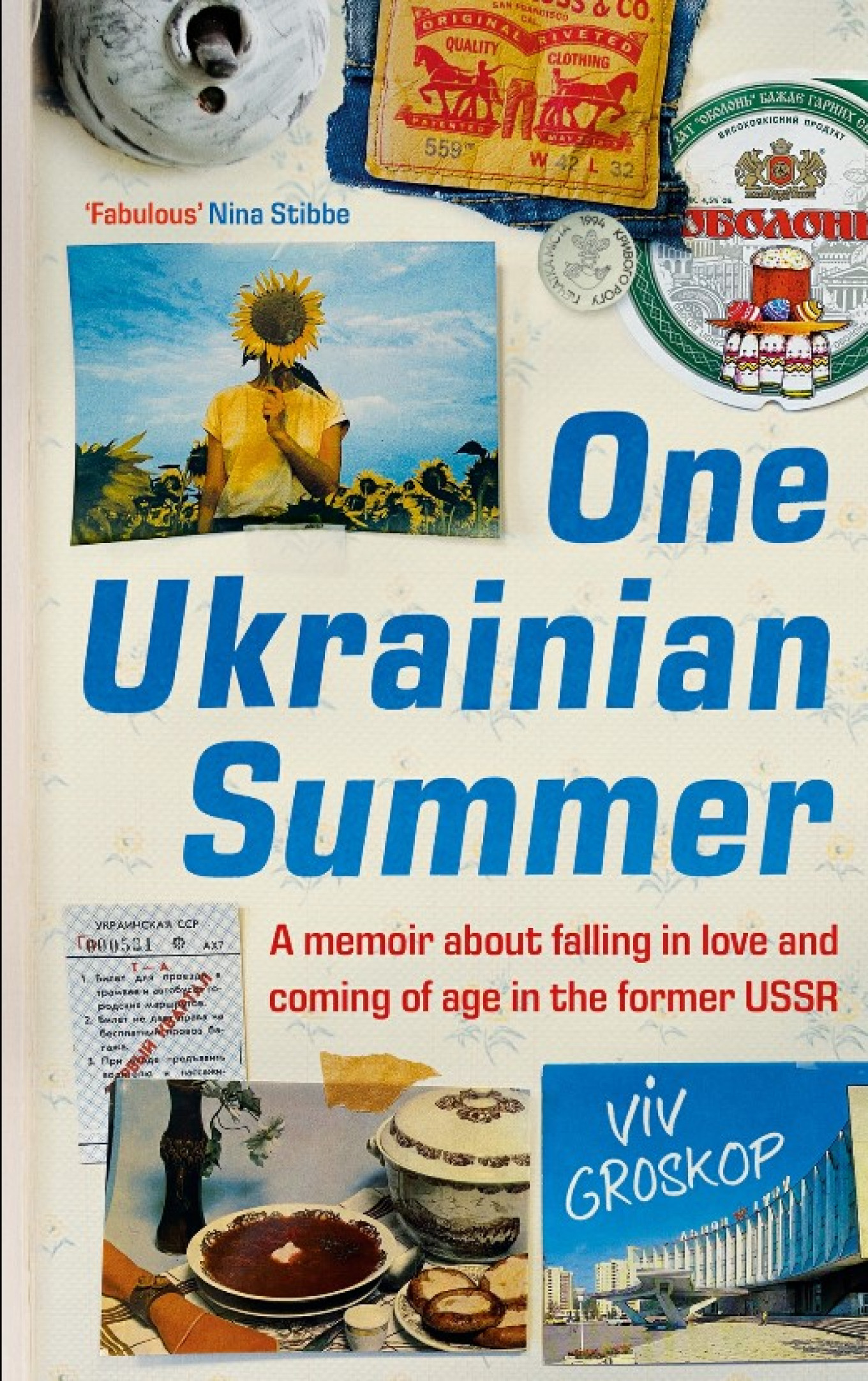

Pushkin House spoke with author, comedian, TV and radio presenter Viv Groskop, who among other accomplishments is a specialist in the Soviet Union and successor states. She talks about her latest book, “One Ukrainian Summer,” about living in Russia and Ukraine in the early 1990s.

When and why did you decide to write the book?

For a long time I had wanted to write about the time I spent with the rock band who called themselves “Ukraine answer to Red Hot Chilli Pepper” [sic] in 1993 and 1994. Every time I raised it with anyone with any influence to get such a book published, I got this answer: “No one knows where Ukraine is.” Which was frustrating. I could have written it and published it anyway but I didn’t quite have the guts. Then suddenly in early 2022 the whole world knew where Ukraine was — for all the wrong reasons. It took me several months to formulate my thoughts on whether it was appropriate to recount these stories now. I asked myself repeatedly how such a book might be helpful in understanding the long-term context and in bringing to life a portrait of Ukraine in peacetime. I realised that if I could partner with PEN International and their program for Writers At Risk then this book had a purpose. (All author proceeds, including the advance, for One Ukrainian Summer go to PEN International.)

Your book focuses on your experiences as a 20-year-old visiting Russia and Ukraine for the first time in the 1990s, and it is full of hope, curiosity and humor. How did you decide which memories to include in the book, and what perspectives can they give us? How did you approach writing in this way, given our current context?

Once I knew that I could partner with PEN International, I felt a freedom to write it in a way that was honest, raw and funny. I wanted to write a book for those of us who knew the former U.S.S.R. after the fall of the Berlin Wall and who remember a more hopeful, perhaps naive time. But I also wanted to write for readers who know nothing about Ukraine or Russia. Because of that, everything I wrote needed to be entertaining, engaging and immersive. All these thoughts guided the memories and stories I wanted to include. I felt a real sense of urgency in the writing as throughout late 2022 into early 2023, I could already feel the news agenda in the U.K. turning away from Ukraine and people “switching off” because it is seen as a “depressing” or “complicated” story. So I wanted to write something that would kind of force people to keep their focus on Ukraine — and that meant writing a book that was intentionally light, easy to read, not off-putting. I was also lucky enough to find a Ukrainian early reader, Yuliya Kostyuk, a lecturer at the University of Essex, who is a speaker of both Ukrainian and Russian. I wanted to include a lot of dialogue in the narrative and her feedback reassured me that a lot of the language I remembered from the time was correct (a mix of Ukrainian, Russian and Ukraine’s third language Surzhyk). I was heavily focused on bringing that time back to life, a time when none of this needed to happen and when people felt like their future was open.

You arrived in Russia at an enormously tumultuous time. What were the reactions of those around you? With your very basic grasp of the language (and no internet!), how did you go about understanding the context you were living in, and what were the difficulties you encountered?

As I think is evident in the book, a lot of my reactions were governed by my age and my own inexperience above anything else. I was 19 when I went to Russia for the first time in 1992 — to St. Petersburg — and 21 when I first went to Ukraine in 1994 — to Kryvyi Rih (Zelensky’s hometown, then Krivoy Rog). I was studying Russian at university from scratch from the age of 18 so when I arrived my language skills were basic. But it was a full immersion immediately and you improved fast because hardly anyone spoke English confidently or intelligibly. In the book I try to recapture the innocence of that time. Chance encounters were the norm. Everyone relied on “the kindness of strangers.” If you needed to know something, you didn’t Google it, you asked someone. The biggest difficulty I encountered was to do with being a “foreigner.” This meant that comparatively you had money (regardless of your background), connections, the ability to travel, supposed access to Levi’s jeans… I hated the superficiality of all that. It meant there was a disparity in status that was hard to overcome. I tried to challenge this disparity by immersing myself even further, cutting off from my family and from English-speaking friends for months at a time. My reaction was pretty extreme but I think a lot of foreigners who spent time in the former U.S.S.R. can remember feeling that way at that time.

You raise some difficult questions for those who learn about “The Region” — from blind spots in research or teaching, to misconceptions or wilful ignorance. Were you conscious of these issues at the time? Do you get the sense that things have changed since then, in how Western academics, journalists and ordinary people learned about Russia, Ukraine and the former Soviet world over the past 30 years?

The past three years since 2022 have forced a huge change in understanding and rightly so. Very few people were conscious of these issues until maybe 15 years ago. In the 20th century over the span of 70 years the Soviet Union and “Moscow” did everything they could to make sure that the focus was always on Russia (and Russian) first. The academic, journalistic and political response outside “The Region” simply followed that pattern. There’s not much point in apportioning blame for that as it was a logical and understandable response. But we do need to admit that it happened.

Plus, in the 1990s the West was focused on this rose-tinted view that democracy had won the day. “The End of History” by Francis Fukuyama came out in 1992. “The Return of History” by Robert Kagan came out in 2008. Between those two books, it emerged that the optimism of the 1990s was tragically misplaced. As I write in the book, when I was at university, the typical exam question was: “What caused the collapse of the Soviet Union?” This question assumes that the Soviet Union did collapse. From the vantage point we have now, we can surely see that in the minds of some, this collapse was not complete. The war in Ukraine has been a belated wake-up call for those of us who know and care about this part of the world.

What is the role that hindsight plays in your book? In the writing process, how did you balance your knowledge and understanding now with your memories of your year abroad?

I was very conscious of the danger of too much hindsight. Because it’s just dishonest. You can only know what you know at the time. At the same time, though, there is no way you can revisit a time in your mind as a writer and not see things with the knowledge that you have now. I allowed hindsight to be an open question in the book. What did I not see then that I can see now? And what can help us to understand the present moment by realising that for a long time we couldn’t see certain things? I’m very interested in the idea of “wilful blindness,” the idea espoused by writer and thinker Margaret Heffernan, who wrote a book of the same name. We are “wilfully blind” to many things until events force us to face up to them. And then suddenly we can’t believe how we could have allowed ourselves to ignore those things.

Are there any lessons in life (or love) that you learnt during that time that have stayed with you?

The lessons I learned at the time as a student during that year abroad were life-changing. That if you immerse yourself and work hard, you can acquire a new language. That most people have the same humanity everywhere. That most of us have more inner resources than we imagine. The lessons I learned over the long-term, thinking back on that time are very different, though, and maybe contradict the earlier lessons. That you see the world in a certain way not because that’s the way the world is but because of how you are and — sometimes — the age you are. That, as an outsider, you can never really get under the skin of a place. That you should never stop revising your understanding of things when new information comes to light. As for a lesson in love? Only that when you are madly in love with someone, nothing will make you see any sense. Especially when you are twenty-one.

This article was originally published by Pushkin House. For more information about the book, see the Pushkin House Book Shop site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.