“Let’s face it,” wrote Alexei Navalny, shortly before his murder in prison, “If a murky assassination attempt using a chemical weapon, followed by a tragic demise in prison, can’t move a book, it’s hard to imagine what would.”

It’s a typically self-referencing touch from an author who lived and died as the main character in his remarkable life.

“Patriot” is part memoir, part manifesto, and part prison diary, and excels as all three. The tale begins as Navalny recovers from the 2020 poisoning attempt in a Berlin hospital, suffering hallucinations, reuniting with his wife and children, and learning to walk and talk again. Long before he is back on his feet he is cracking jokes at Putin’s expense.

The late opposition leader made the uncompromising decision to return to Russia after his discharge from hospital and was arrested as soon as his plane touched down. Here the linear narrative breaks, as Navalny takes us back through his life.

Born in 1976, Alexei had an ordinary Soviet childhood in the military town of Tambov. He collected chewing gum from around the world, he read widely but enjoyed playing the class clown. He headed to university with the upheaval of the nineties in full swing. His classmates were more interested in fast cars and girls than training to be lawyers and cheated their way through the course. Navalny remembered this period with some fondness, although he still agonized over a bribe he once paid and mused that could have drifted into the military or police.

Instead, Navalny got involved with Russia’s fledgling democratic system, going on to stand as a mayoral candidate for Moscow, and becoming the leader of the Anti-Corruption Foundation.

He writes: “I wanted to see a politician appear who would undertake all sorts of interesting projects, and cooperate directly with the Russian people…I waited and waited, and one day I realized I could be that person myself.”

Navalny bought small shares in state-owned companies and made theatrical appearances at shareholding meetings, demanding to see how his money was used. The Anti-Corruption Foundation shamed Russia’s energy giants for their habitual embezzlement and bribery and was an early pioneer in using the Internet to reach the public. Their video “Putin’s Palace” racked up millions of views.

Putin was slow to catch on to the potential of online activism, and the opposition took advantage of this, building a movement that coordinated protests at regional centers across the whole country. Eventually the regime had enough, using “lawfare” and violence to punish Navalny and his family.

Navalny would have been aware of the book title’s irony, yet he sincerely considered himself a patriot in the true sense of the word. He loved Russia “one of the components from which I am made…like an arm or a leg” – he writes – and he chose to die rather than accept the conditions of the state that became his personal enemy.

Navalny had ample time during his convalescence and imprisonment to reflect on his political views. These passages are insightful but do not settle some controversies that surrounded its author in life. He explains why he shared a platform with far-right nationalists early in his career – “I felt sure that a broad coalition was needed to fight Putin”– but doesn't really explain what it means to be a nationalist. As a politician Navalny had to fight for the right to be heard and never held an elected position. We are left to imagine a future in which he became a leader.

The final section of Patriot feels like a different kind of a book. Navalny himself quips that the “prison diary” is a genre full of “clichés,” yet his writing is as moving as classics like Solzhenitsyn’s “One Day in the Life of Denisovich.” As Navalny was smuggling notebooks to his lawyers one at a time and writing without reference to his previous words, these passages have an immediate quality. In prison Navalny learns to find joy in small moments – he is ecstatic when he gets hold of salt to make a simple salad with tomatoes and cucumbers and relieved when the prison van’s radio is set to a decent station.

Despite the bleak setting there is humor in the interactions between Russia’s most famous political prisoner and the murderers, drug-addicts and thieves he meets in jail. Navalny describes a dispute between two “grizzled old dudes with no teeth” about the age of singer Billie Eilish: “one [of them] tells us the details of her biography…they watch television all the time, so they know these things.” Poignantly, Navalny wants to share the joke with his teenage daughter, whom he would never see again.

The regime tried to break Navalny by taking him to increasingly grim prisons, isolating him, and denying him medical care. The story becomes a battle between the bright mind of one man and the four walls closing in around him. It’s hard to finish these chapters knowing how the story ends, but Navalny’s courage inspires hope to the last. He accepted his fate and found faith. As we read his last lines, it does not seem that we are witnessing a defeat.

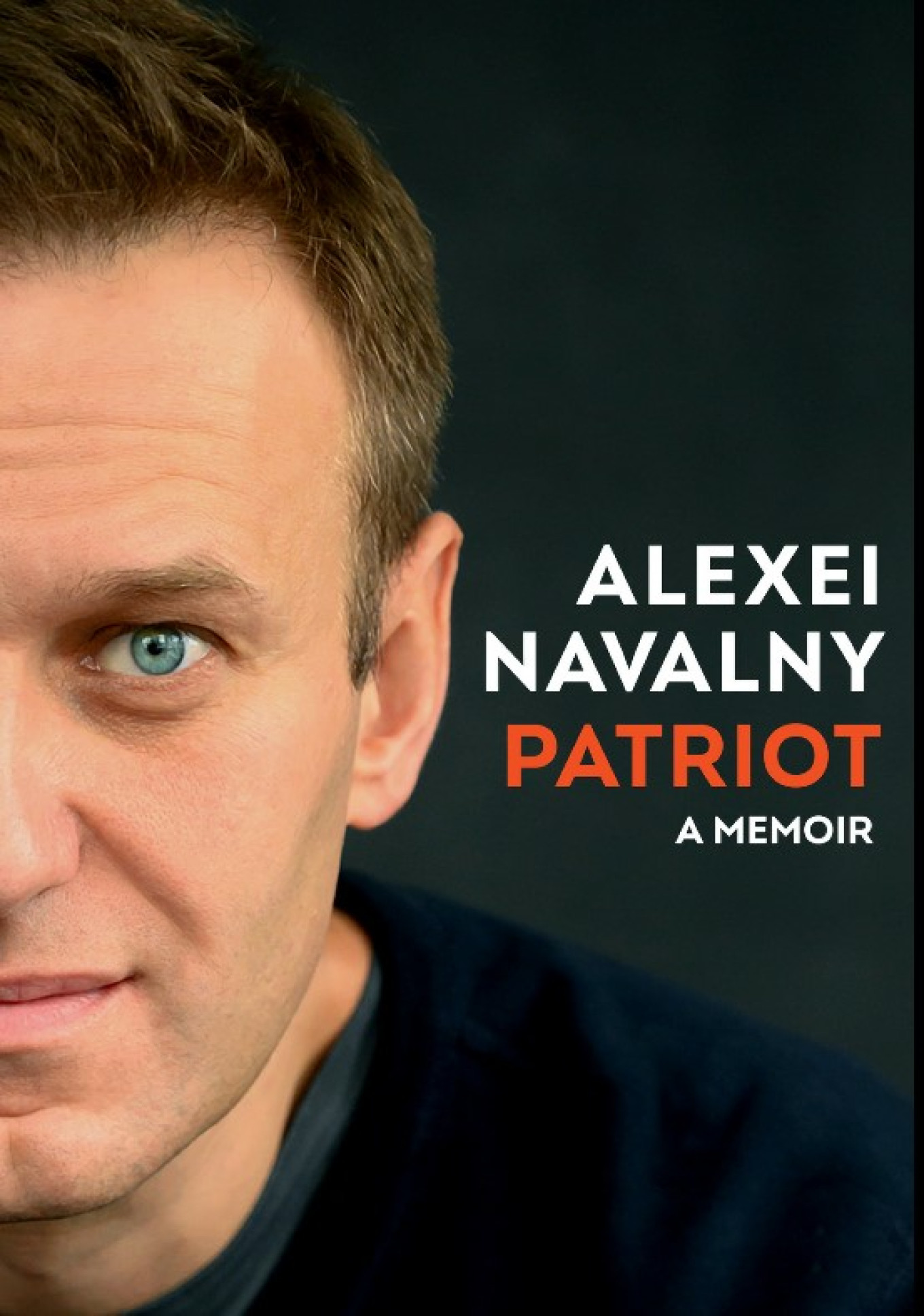

Patriot: A Memoir

Part 1: Near Death

Boarding is announced, and at 7:35 we show our passports and get on the bus that will drive us the 150 meters to the plane.

It is a crowded flight, and there is a bit of a commotion on the bus. A guy recognizes me and asks for a selfie. Sure, no problem. After that, other people shed their inhibitions, and perhaps ten more squeeze toward me to get a photo. I smile happily into other people’s phones and, as always at such moments, wonder how many really know who I am and how many have decided to take a photo just in case I’m somebody. This is a perfect illustration of Sheldon Cooper’s definition in The Big Bang Theory of a minor celebrity: “Once you explain who he is, many people recognize him.”

As we head onto the plane, there are more photographs, and Kira, Ilya, and I are among the last to take our seats. This makes me anxious because I have a backpack and a suitcase that need to be stowed. What if all the overhead bins are already taken? I don’t want to be the sad passenger who rushes around the cabin asking the crew to find a place for his hand luggage.

In the end, everything is fine. There is room overhead for the suitcase, and I put my backpack between my feet at the window seat. My colleagues know I much prefer to sit by the window so they can insulate me from anyone who might want to discuss the political situation in Russia. I’m generally happy to chat with people, just not on a plane. There is always a lot of background noise, and I really don’t relish the prospect of having a face twenty centimeters away shouting at me, “You investigate corruption, right? Well let me tell you my case.”

Russia is built on corruption and everyone has a case.

My mood, already great, gets even better as I look forward to three and a half blissful hours of complete relaxation. First I’ll watch an episode of Rick and Morty, then read.

I fasten my seat belt and take off my sneakers. The plane starts moving down the runway. I delve into my backpack, take out my laptop and headphones, open the Rick and Morty folder, and choose a season at random, then an episode. I’m in luck again; this is the one where Rick turns into a pickle. I love it.

A passing flight attendant looks askance but does not ask me to close the laptop as mandated by an outdated aircraft security regulation. It’s one of the perks of being a minor celebrity. Today is going really well.

Then it stops going well.

Thanks to that kind flight attendant, I now know precisely the moment when I felt that something was wrong. Later on, after eighteen days in a coma, twenty-six days in intensive care, and thirty-four days in the hospital, I will put on gloves, clean my laptop with an alcohol wipe, open it, and discover that the episode was twenty-one minutes in.

It takes an event really out of the ordinary to make me stop watching Rick and Morty during takeoff —turbulence would not be enough — but I am looking at the screen and can’t concentrate. Cold sweat begins to run down my forehead. Something very, very odd and wrong is happening to me. I have to close the laptop. Icy sweat runs down my forehead. There is so much that I ask Kira, who is stitting next to me on my left, for a tissue. She is absorbed in her ebook and, without looking up, takes a pack of tissues from her bag and hands it to me. I use one. Then a second. Something is definitely not right. It’s not like anything I have ever experienced. It’s not even clear what I’m experiencing. Nothing hurts. I just have a weird sense that my entire system is failing.

I decide I must be airsick from looking at the screen on takeoff. I say uncertainly to Kira, “Something is going wrong with me. Do you think you could talk to me for a bit? I need to concentrate on the sound of someone’s voice.”

It is, undoubtedly, a strange request, but after a moment’s surprise Kira starts telling me about the book she is reading. I can take in what she is saying, but it involves an almost physical effort. My concentration is disappearing by the second. Within a couple of minutes I am only seeing her lips move. I hear sounds, but cannot understand what is being said, although Kira tells me later that I held out for about five minutes, muttering “Uh-huh” and “Aha” and even asking her to clarify what she’d said.

A flight attendant appears in the aisle with a cart — drinks. I try to think whether I should have some water. Acording to Kira, he stood there, waiting. I looked at him silently for ten seconds until both she and he began to feel awkward. Then I said, “I guess I do actually need to step out.”

I decided I should go and splash my face with cold water and that would make me feel better. Kira gave a shove to Ilya, who was asleep in the aisle seat, and they let me out. I was in my socks. It wasn’t that I didn’t have the strength to put my sneakers back on: it was just that right at that moment I couldn’t be bothered.

Luckily the toilet was free. Every action calls for reflection, although ordinarily we don’t notice that. Right now I had to make a conscious effort to understand what was going on and what I needed to do next. This is the toilet. I must find the lock. There are things of different colors. This is probably the lock. Slide it this way. No, that way. Okay, there is the faucet. I need to press it. How do I do that? My hand. Where is my hand? There it is. Water. I need to splash it on my face. At the back of my mind there is just one thought, which does not call for any effort and crowds out everything else: I can’t take it anymore. I rinse my face, sit down on the toilet, and realize for the first time: I’m done for.

I didn’t think, I’m probably done for: I knew I was.

Try touching your wrist with a finger of your other hand. You feel something because your body releases acetylcholine and a nerve signal notifies your brain of the action. You see it with your eyes and identify it through your sense of touch. Now do the same with your eyes closed. You don’t see your finger, but you can easily tell when you touch your wrist and when you don’t. That is because, after acetylcholine transmits a signal between nerve cells, your body secretes cholinesterase, an enzyme that stops that signal when the job is done. It destroys the “used” acetylcholine and with it all traces of the signal transmitted to the brain. If that did not happen, the brain would receive signals about the wrist being touched over and over, millions of times. It would be similar to a distributed denial of service (DDOS) attack on a website: click once and the site opens; click a million times per second and the site crashes.

To cope with a DDOS attack, you can reload the server or install a more powerful one. With human beings it’s less straightforward. Bombarded by billions of false signals, the brain becomes completely disoriented, unable to process what is going on, and eventually shuts down. After some time a person stops breathing, which, after all, is also controlled by the brain.

That is how nerve agents work.

I make one more effort and mentally check out my body. Heart? No pain. Stomach? Everything fine. Liver and other internal organs? Not even the slightest discomfort. All in all? Dreadful. This is too much, and I’m about to die.

With difficulty I splash water on my face a second time. I want to return to my seat, but don’t think I will be able to get out of the toilet by myself. I won’t be capable of finding the lock. I can see everything clearly. The door is in front of me. The lock is there too. I’ve got enough strength, but keeping that stupid lock in focus, reaching out, and sliding it in the right direction are all very hard.

Somehow I manage to get out. There is a line of people in the passageway, and I am able to see they are not happy. I’ve probably been in the toilet longer than I thought. I’m not behaving like a drunk — I don’t stagger, nobody is pointing at me. I’m just another passenger. Kira told me afterward that I left my window seat quite normally, getting past her and Ilya easily enough. I just looked very pale.

I am on my feet in the aisle and tell myself to ask for help. But what can I ask the flight attendant? I can’t even articulate what is wrong or what I need.

I look back toward the seats but then turn the other way. Now I am facing the galley, five square meters with meal carts—the place you walk to on a long flight if you want something to drink.

Real writers are special people, you know. When I am asked what it’s like to die from a chemical weapon, two associations come to mind: the Dementors in Harry Potter and the Nazgûl in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. The kiss of a Dementor does not hurt: the victim just feels life leaving. The main weapon of the Nazgûl is their terrifying ability to make you lose your will and strength. Standing in the aisle, I am kissed by a Dementor and a Nazgûl stands nearby. I am overcome by the impossibility of understanding what is happening. Life is draining away, and I have no will to resist. I’m done for. This thought swiftly and potently fully takes over from I can’t take it anymore.

The flight attendant looks at me quizzically. He appears to be the same guy who pretended not to notice my laptop. I make one more effort to come up with words I can say to him. To my surprise I manage to say, “I have been poisoned and am about to die.” He looks at me without alarm, surprise, or even concern — indeed, with a half smile. “What do you mean?” he asks. His expression changes radically as he watches me lie down at his feet on the floor of the galley. I don’t fall over, don’t collapse, don’t lose consciousness. But I absolutely feel that standing in the aisle is pointless and silly. After all, I am dying and people die —correct me if I’m wrong — lying down.

I lie on my side. I stare at the wall. I no longer feel any awkwardness or anxiety. People start running around, and I hear exclamations of alarm.

A woman shouts close to my ear, “Tell me, are you feeling ill? Tell me, are you having a heart attack?” I shake my head feebly. No, I have no problem with my heart.

I have just enough time to think, It’s all lies what they say about death. My whole life is not flashing before my eyes. The faces of those dearest to me do not appear. Neither do angels or a dazzling light. I am dying looking at a wall. The voices become indistinct, and the last words I hear are the woman shouting, “No, stay awake, stay awake.” Then I died.

Spoiler alert: actually, I didn’t.

Excerpted from “Patriot. A Memoir” written by Alexei Navalny, translated by Arch Tait and Stephen Dalziel and published by Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2024 by Yulia Navalnaya and the Estate of Alexei Navalny. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Footnotes have been removed to ease reading. For more information about the this book, see the publisher’s site here.

“Patriot. A Memoir” has been shortlisted for this year’s Pushkin House Book Prize, which will be awarded on June 19 in London. Tickets for the ceremony are available here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.