The Soviet factory kitchen invented in the 1920s was supposed to be a breakthrough into a bright future — a future where women were not oppressed in the kitchen and where beautiful and free people could sit and discuss the electrification of the country and the collapse of global imperialism. What a shining and worthy project!

There was only one problem: It didn't work.

How and why did this type of public catering come about? To find the answer, we need to take a culinary time machine back almost a century — but first we need decide if we really want to go back. Let us explain.

In 1917, the new Russia inherited the difficult problem of providing food for the working class. There were taverns, pubs and factory cafeterias that produced what was clearly substandard food, and there was dinner at home, hastily prepared by wives exhausted after work. There was neither variety nor any real culinary pleasure.

Soviet public catering gave people what they were used to, whether the Bolsheviks wanted to or not. It’s hard to instill a taste for healthy food at a time and place where they could not exist. This was a time when a plate of borscht with lard and fried chicken with mushy, overcooked grain was considered a culinary masterpiece. So the “start” of Soviet cuisine was largely in place as it developed in the 1920s.

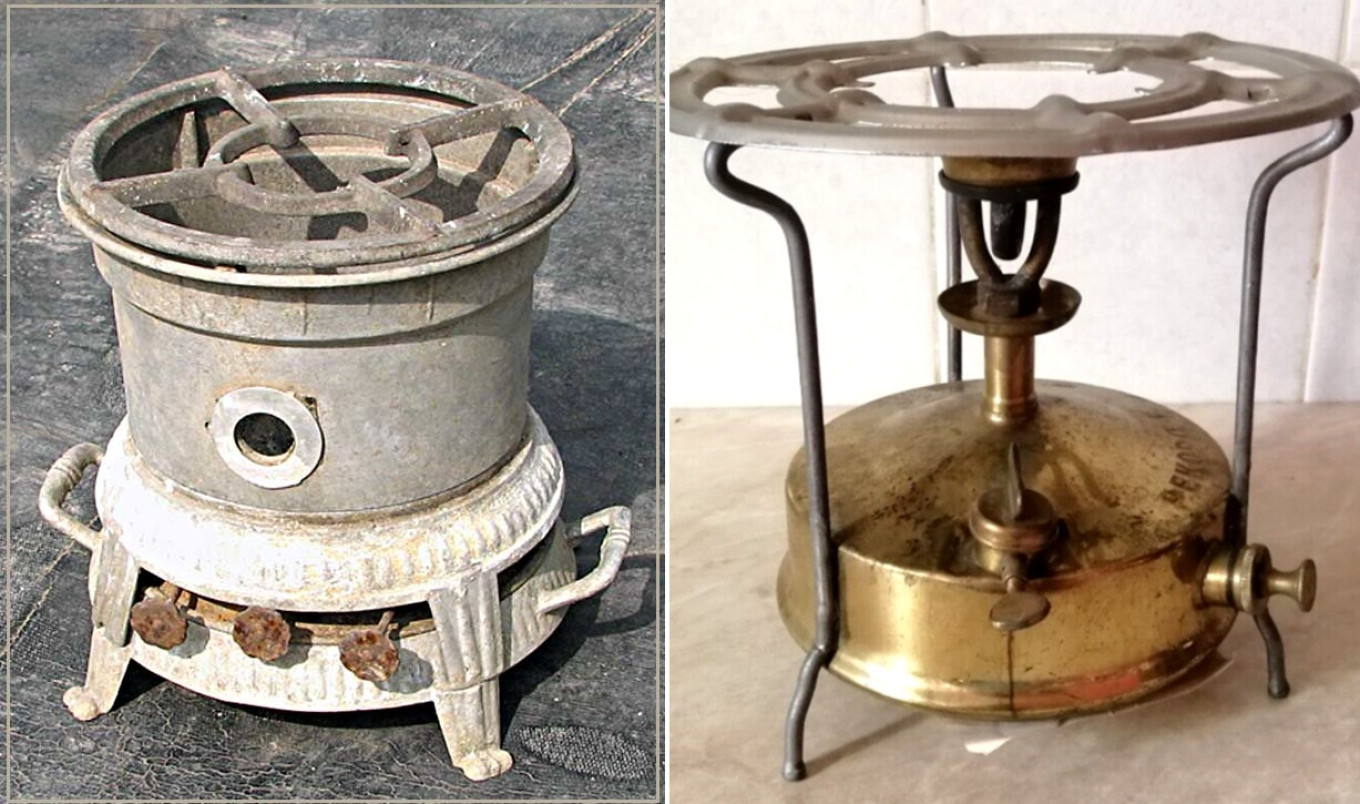

Kitchen equipment is also important, and in this regard, home life was getting worse. While a full stove still allowed for culinary creativity, the kerosene stove that replaced it severely limited the cook's imagination. The primus stove, which we now know only from books and films, was a step forward compared to the kerosene stove.

The primus stove made it easier to regulate the heat and was more convenient to use. However, from a culinary point of view, it was simply awful. These appliances did heat dishes relatively quickly. But it was almost impossible to use any culinary techniques on them such as sautéing, braising, or stewing.

The revolutionary upheaval of all the historical foundations of Russia affected the kitchen and nutrition along with everything else. A year before the Bolshevik Revolution in the fall of 1916 a system of ration cards was put into place to guarantee workers a minimum amount of food at a fixed price. So these measures were by no means an invention of the Bolshevik government.

The authorities did try to remedy the situation. One of the solutions at the time was to organize public cafeterias in places of business. Until 1917, for example, there were only a few "public cafeterias" in all of Petrograd. Shortly after the October Revolution, they opened everywhere — at train stations, in taverns, and in movie theaters. And they were largely responsible for saving people from starvation. People could buy a more or less nutritious lunch (dinner at home was catch-as-catch-can). But nutritious did not mean “tastes good.”

Gradually a new format of public cafeterias emerged. Warehouses and vegetable storerooms were set up next to the kitchens. In the old days, fresh vegetables were delivered to restaurants every morning. But a new era had dawned.

The dining rooms were equipped with washbasins for washing hands before meals, changing rooms to get out of dirty work clothes, and “culture corners” with newspapers and magazines

This was all in keeping with the general spirit of socialism. As Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar for Education, said: “Our task is to eliminate household work... True, complete, ultimate liberation is when everyday life has been socialized…” Actually, he didn’t just dream about this — he and his colleagues carried it out in real life.

One way was the idea to build huge enterprises where food would be prepared, cooked, and sent to workers' cafeterias. Thousands of ordinary townspeople could also eat in these beautiful, clean, and cultured surroundings.

As the authors of the book "Lunch Factories" wrote in the early 1930s: “The task of providing workers with hot meals at the production site was not easy. It was too expensive to build a kitchen at every enterprise. We had to organize the delivery of ready-made meals at factories where they would be distributed.”

But these factory kitchens were being developed in difficult economic times. Before the war, Sergei Protopopov, the former chief chef of Moscow, was the director of the cafeteria for the first Bolsheviks. He is quoted by Olga and Pavel Syutkin in their book “The True History of Soviet Cuisine”: “Meat patties are prepared in the factory kitchen. Everything is done by the book, with the correct amount of meat. Then the meat patties are sent to the workers’ cafeteria. On the way, they cool down and dry out. Once there, they’re put into the oven to be reheated, where they shrink. Then the police department for combating theft of socialist property arrives, weighs the now underweight meat patties, arrests the cook, and charges him with a felony.” Protopopov said that he repeatedly refused to participate in the trials of these cooks because he understood that they had nothing to do with it.

These problems were obvious to professionals. That is why in 1931 the authorities decided to change the format. From then on, factory kitchens stopped providing ready-made meals and began to make ready-to-cook meals that were then sent on to factory cafeterias.

Despite all these efforts, much of the problem came down to personnel. The Soviet authorities could buy plans and parts for bread factories, electric boilers, and sausage-making production lines abroad and build them. But they had to train villagers who had come to the city in droves looking for work. That's when the old idea of culinary schools reappeared.

“I arrived in Dnipropetrovsk in the midst of the construction of the Dnipro Hydroelectric Power Plant,” recalled Fyodor Galenyshev, director of the factory kitchen. “There was a major breakthrough factory kitchens appeared, but there was no skilled labor and no technical director. We received good raw products, but we fed people rotten food. For example, instead of white bread they used black bread for meat patties, which spoiled the meat because black bread causes fermentation.” The cooks had a lot to learn.

After World War II there were just as many problems. The situation with factory kitchens was particularly dire in Moscow in the mid-1950s. Almost all of them had been taken over by other organizations. The Oktyabrskaya factory kitchen became a club, the Krasnopresnenskaya kitchen was a maternity hospital, and the factory kitchens on Leningradskoye and Mozhaiskoye highways became institutes. This happened despite the fact that the Sport factory kitchen on Leningradskoye Shosse had served 50,000 meals a day in the past!

By the 1960s, the project had become obsolete. There were many reasons for closing factory kitchens. Cafeterias at enterprises and institutions had effectively taken over their role. Food supplies in the U.S.S.R. were organized by ministries: the military and defense industry got the best, while students and workers in small factories got the worst. This conflicted with the logic of factory kitchens, which was to provide food for everyone. It was impossible to ensure adequate quality “for everyone” as food shortages became more prevalent. Finally, mass cultural and leisure activities lost popularity when housing construction was expanded greatly under Nikita Khrushchev. The kind of celebration of an entire office that was depicted in the film “Carnival Night” became a thing of the past.

The factory kitchen was supposed to shape a “new type of person”: someone who used cutlery, ate from earthenware dishes, read newspapers, played board games, and listened to beautiful music. An orchestra played in factory kitchen halls, fresh newspapers were available, and chess and checker boards stood on tables. The people of the future, freed from the hardships of everyday life, educated, and ideologically correct — that's who sat at the tables in the spacious halls of the factory kitchens. Or rather, that's who was supposed to sit there. It didn't work out that way.

Remember the meat patties that dried out on the way from the factory kitchen to the canteen? Unlike those cooks, we make them with our favorite recipe — and serve them hot.

Simple Meat Patties

Ingredients

- 250 g (9 oz) beef

- 250 g (9 oz) pork

- 1 small onion

- 125 g (4.5 oz) stale white bread without crusts

- clarified butter for sautéing the onion and frying the meat patties

- 12 g (2 tsp) salt

- freshly ground black pepper

Instructions

- Dice the onion and sauté lightly (until transparent and slightly golden) in a small amount of clarified butter. Cool.

- Pour cold water over the stale white bread and leave for 5 minutes. Then squeeze out the excess water.

- Cut the meat into 1 to 1 1/2 cm (1/4 to ½ inch) cubes.

- Run the prepared ingredients through a meat grinder with a fine mincing plate, alternating between meat, onions, and bread.

- Season the minced meat with salt and pepper. To ensure your cutlets are juicy, knead the minced meat with a fork or a special whisk.

- Mix the minced meat thoroughly, cover with plastic wrap, and refrigerate for one and a half to two hours.

- After that time is up, remove the minced meat from the refrigerator, mix again with a fork and form oval patties.

- Place the frying pan on the heat and add the melted butter to the cold pan. There should be enough butter to cover about 1/3 of the sides of the patties. Turn the heat to high and heat the pan. As soon as the butter melts and the first bubbles appear, you can add the first patty. The patties should immediately begin to fry. Fry the patties on both sides until golden brown.

- Reduce the heat to medium and continue frying the patties until done, turning them over several times. They are done when a fork pierces the center and the meat juices run clear. Remove the finished patties from the pan immediately—do not leave them in the butter!

- The second way to cook the patties to place them in an oven preheated to 160°C /320°F for 20-25 minutes.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.