Everyone loves gingerbread. Unlike okroshka, Lenten buckwheat with mushrooms or steamed turnips, this mainstay of old Russian cuisine does not have nay-sayers.

Gingerbread is a universal favorite — in Russia and all over the world. In fact, experimenting with each other’s gingerbread has been a very successful example of cultural exchange.

The notion that gingerbread was invented in Russia exists only in the clouded consciousness of Putin's professional patriots. It’s clear to specialists that despite their love for “original Russian gingerbread,” this sweet only appeared in more or less familiar form in the 17th century. In Western Europe sweets that are practically indistinguishable from classic gingerbread were already part of everyday life in the 13th-14th centuries. Nuremberg gingerbread, called lebkuchen (Nürnberger Lebkuchen), was known far and wide. There was a simple explanation for this: Nuremberg had a monopoly on the spice trade since 1300.

In Russia, the first mention of the word for a spice cake (пряник) is only found in the second half of the 16th century. For example, there is mention of them in the records book containing a description of the plots of land and population of Kazan in 1568.

In the western regions of Russia gingerbread was soon traded abroad. Proof of this can be found in the inventory of goods of the Novgorod merchant Tikhon Yakimov that has been preserved in the archives. “Last year, 1656, in the shop in Stockholm, he writes, “before traveling to Russia I left 10,000 gingerbread plovers worth 35 thalers [a thaler, minted in Lubeck, weighed 30 grams of silver].”

A plover is a kind of water bird. Either the gingerbread was in the form of a bird, or the bird was depicted on it. In any case, this shows that Novgorod gingerbread was exported to Europe in the middle of the 17th century — and in very large quantities.

Was Novgorod the only place with domestically made gingerbread? Of course not. But the details might not be so patriotic and celebratory. Livonia (a region in modern Latvia and Estonia) was in the center of military conflicts with the Russian state since the second half of the 15th century. As a result of these numerous conflicts, under the reign of Ivan the Terrible there was mass resettlement of Livonian inhabitants — Estonians and Germans — to the Kazan lands.

So, chances are these settlers were responsible for that first mention of gingerbread in Kazan in 1568.

As for life in Moscow, even at the end of the 17th century, classic spiced gingerbread was still a rarity. But honey kovrizhka — a kind of transitional product between honey bread and classical gingerbread — was even served at the table of the tsar.

Unlike ordinary honey bread, kovrizhka already had a special pattern or drawing on the surface. But the use of spices was limited. For example, in 1672 on the occasion of the birth of Tsarevich Peter Alexeevich (the future Peter I) there were 120 dishes and sweets served including, “a large sugar kovrizhka with the coat of arms of the State of Moscow, and second sugar and cinnamon kovrizhka.”

In Russia the 18th century was a time of rapid integration of foreign cuisines. The flood of “foreign specialists” who came to the country from their European homelands brought not only knowledge of ship rigging but also their love for gingerbread. “Having been in Holland for a long time, the Emperor [Peter the Great] made acquaintance with many shipbuilders there,” writes Russian historian and later Decembrist Alexander Kornilovich in 1824. “They brought a gift of cheese for him, linen for the Empress, and gingerbread for the boys, the Grand Dukes Peter Petrovich and Peter Alexeevich.”

In addition to traditional exports (honey, hemp and furs), Russian trade was expanding to shipments of gingerbread — at the same time they were importing it from Europe. On Sept. 1, 1766, a decree of Catherine II established new customs tariffs, but gingerbread was imported into and exported out of Russia without any duties.

A hundred years later, the volume of this business was surprising. The “Review of Russia's Foreign Trade for 1890” wrote about the export of 11,591 poods (almost 190,000 kilograms) of gingerbread worth 109,000 rubles. For comparison, the traditional export of honey amounted to only 80,000 rubles that year.

In Russia’s big cities, people were familiar with both domestic and foreign gingerbread. The 1792 “Commercial Dictionary” described some of the varieties of European pastries: “French gingerbread is a kind of dough made with eggs and sugar, sometimes with honey, which is baked between two iron plates.”

But notice the phrase “sometimes with honey.” It captures the very beginning and rapidly growing distinction between Russian and European gingerbread. Before that, gingerbread in Europe as well as in Russia was made with honey.

New times meant changes in the ancient craft of gingerbread making. By the 18th century in some European countries the production of sugar from sugar cane produced a surfeit of a kind of molasses — the thick syrup that was a by-product of the refining process. The best part of it — “golden honey molasses” — was used in gingerbread. It was also called “cane honey,” although it was only sugar cane juice boiled down to a thick consistency.

In Russia the abundance of honey meant there was simply no point in using a substitute. Domestic sugar production before the invention of beet sugar technology was only used to purify imported raw sugar. There was simply no by-product of molasses in the production cycle.

The popularity of Russian gingerbread abroad is just one example of how Russian cuisine would become known in Europe. By the mid-19th century, Russian gingerbread makers were showing their wares at World Fairs.

At the 1900 World Fair in Paris, quite a few Russian manufacturers decided to showcase their gingerbread. Together with the famous factory Einem (the future Soviet “Red October”) there were gingerbread makers from Tula: Vasily Grechikhin and Ksenia Belolipetskaya. The tea factory of K. and S. Popov built an improvised Russian tea house on the Esplanade des Invalides, where they served gingerbread made in Tver and Gorodets, a town not far from Nizhny Novgorod.

There is still a legend in Tula that Grechikhin built his pavilion in Paris out of gingerbread — supposedly even the roof was made of gingerbread. Fair records shows that both gingerbread producers from Tula received bronze medals. Gingerbread became another theme that united France and Russia.

After all this, you might wonder who had the rights to gingerbread. Which country considers gingerbread the greater national treasure? A slightly funny episode crowns this long-standing dispute. In 1892, an alliance agreement was concluded between Republican France and Russia. Later it was supplemented by a military convention. And in October 1896, Tsar Nicholas II paid a visit to Paris.

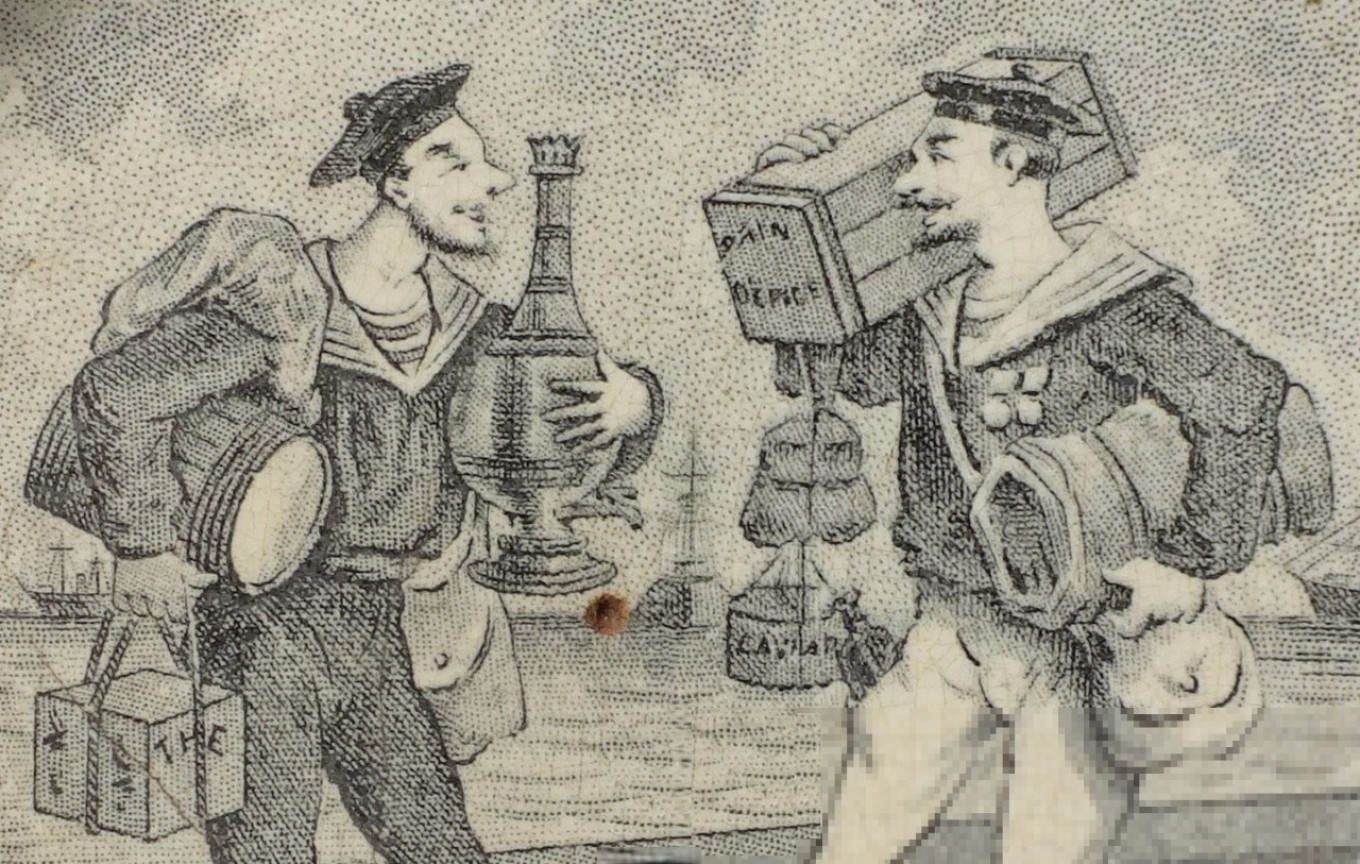

The famous faience factory in Choisy-le-Roi celebrated this event by producing a series of plates on the theme of “France and Russia.” One of them depicted two sailors with the caption: “Small gifts help friendship develop” (Les petits cadeaux entretiennent l'amitié).

But the image is a bit of a riddle: Who is who? One sailor is holding a samovar (looks Russian), a barrel (of French wine?) and a box of tea. Another carries a box of gingerbread (pain d'épices) on his shoulder, with a jar of caviar dangling below, and a suspicious bottle (of vodka?) sticking out of his pocket. This is a very confusing image. Is the Frenchman giving the Russian gingerbread, or is the Russian treating the Frenchman?

While your guests contemplate this riddle, treat them to the gingerbread on the plate. Here’s one of our favorite recipes.

Buttery Honey Gingerbread with Raisins

Ingredients

- 200 g (1/2 c plus 2 Tbsp) honey

- 100 g (1/2 c) brown sugar

- 80 g (5 Tbsp and 1 tsp) butter, melted

- 3 egg yolks

- 300 g (1¾ cup plus 2 Tbsp) flour

- 1/2 tsp baking soda

- 3/4 -1 tsp spice mix (mix of 1/2 tsp cinnamon, 1/4 tsp nutmeg, 1/4 tsp ground cloves, 1/4 tsp allspice, 1 tsp ginger)

- 100-150 g (1/2 to ¾ c) small seedless raisins (or dried currants, cranberries)

- If you wish, you can add nuts finely chopped in a blender, alone or with the raisins.

Instructions

- Heat honey, butter, sugar, baking soda and spices in a thick-walled pot over low heat or over a water bath to a temperature of 75°C /165°F to 80°C/175°F. Remove from heat.

- Pile the flour into a mound, make a depression in the center and add the yolks.

- Add the honey mixture and knead the dough.

- Add nuts, raisins or other dried berries.

- Wrap the dough in cling film and put it in the refrigerator for 2-3 hours.

- Turn on the oven to preheat to 200°C /390°F.

- To make the gingerbreads, form a round mass and use a pastry ring to cut rounds. The standard weight of a round gingerbread is 40 g (1½ oz). It’s best to weigh out the rounds to ensure that the gingerbreads are the same size.

- If the discs are mounded, roll out the dough to 1.5-2 cm (1/2 -1 inch).

- Bake the gingerbread in the preheated oven for 15-17 minutes.

- Make a glaze from the remaining egg whites (see below).

- Cool the gingerbread slightly and cover with the glaze.

Glaze

Ingredients

- 1 egg white

- 150 g (3/4 c) powdered sugar

- 8 g (1/2 Tbsp) lemon juice

Instructions

- Beat the egg white on low speed until slightly frothy.

- Add the powdered sugar and continue to beat. The mixture should thicken slightly and turn white. Add lemon juice and stir.

- Continue to beat to the consistency you prefer. If you whip it to a light foam, the coating will be thin and transparent. If you whip it to firm peaks, the gingerbread will be covered with a thick, dense glaze

- Frost the cooled gingerbread.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.