What’s a tea party without a samovar! The samovar — chubby, steamy, shiny and imposing — has been the center of every holiday table and an indispensable part of Russian feasts. And the samovar has been a good friend to all regardless of class, honored equally by the poor man and the tsar.

Russia has developed its own tea drinking rituals over the years. For a long time tea was an urban drink, and Moscow set the tone.

Here the early 20th-century writer Alexander Vyurkov beautifully described tea drinking in the capital city: “Muscovites drank tea in the morning, at noon and always at four o'clock. At four in the afternoon samovars were boiling in every house. Tea rooms and inns were full, and life stopped for a while.... If the coals in the samovar crackled and ‘sang songs,’ the superstitious Muscovite rejoiced: This was a good sign. But if the samovar suddenly began to whistle as the coal embers were dying down, the Muscovite grabbed the lid, put it on the samovar and then began to shake it. He might have silenced the whistling, but for a long time the Muscovite would anxiously expect trouble. The worst omen, however, was if the samovar sprung a leak. Trouble would surely follow.

Above: The Museum of Russian National Drinks (Gavrilov Posad, Ivanovo region) has an enormous collection of samovars. This and other photos of samovars were taken there.

It was customary for merchants and the lower middle class to keep water boiling in the samovar all day long. Among the merchants tea drinking had to be done in style. They would spend long hours at the tea table, drinking up to 20 cups. A separate table with all sorts of appetizers was laid for tea. Before tea people ate salty food, such as caviar and pickled fish, and then drank several samovars dry while eating all sorts of “nibbles,” that is, cookies and sweets.

A proper Russian tea party had four changes of appetizers. Merchants and the lower middle class liked to drink tea with round bread sticks and rolls, taking a bite of sugar placed on the saucer, and always with their little finger sticking out — which was considered very vulgar among the nobility.

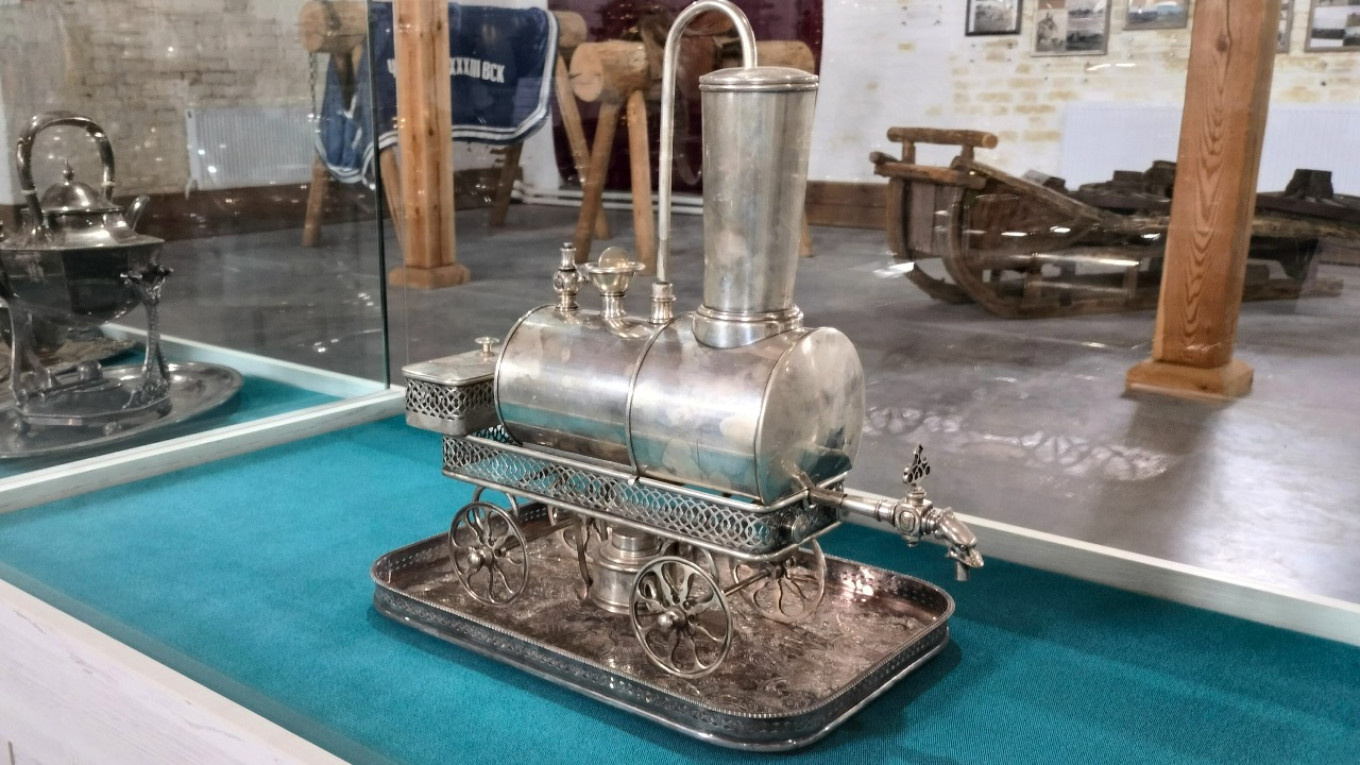

Above: A working model of a steam-engine samovar. If you don't pour tea for a long time, it rolls over to you on its own.

The custom of spicing tea with Madeira or rum was contrary to strict traditions. But the “Old Notebook” by Prince Pyotr Vyazemsky included a story in the section “Notes on food and dining, as well as on the subject of drinking. “Once when a host was pouring rum into a cup of tea, his hand quavered for a moment and he poured in too much and exclaimed, ‘Ach!’Then he asked his guest if he should pour him some rum, too, but this time he poured very carefully and rather reluctantly. ‘No,’ said the guest, ‘I’ll have some of the Ach! that you have’.”

Since the middle of the 19th century, drinking tea from a samovar has been a national tradition in Russia. Despite the very high cost (a samovar was not cheap — it cost about as much as a cow), it was welcomed into working-class and peasant families and became an indispensable attribute of every Russian home. It was used not only at home, but even taken on trips and to parties. For this manufacturers made "traveling" samovars that were easy to transport: the polyhedral, cubic or sometimes cylindrical samovars had removable legs and handles that could be easily attached upon arrival.

Above: “Vase” samovars from the Vorontsov factory in Tula (late 19th century) and an earlier model from the mid-19th century.

Properly run homes had two samovars: one for everyday use and one for holidays and guests. People would spend a long time carefully choosing the right samovar since they would use it for many years. To encourage people to buy better and higher quality samovars, manufacturers stamped their wares with their own trademark as well as images of medals received at exhibitions, often international. For example, Batashevsky (Batashev Brothers) samovars were stamped with medals from four world exhibitions: Paris, London, Chicago and Nizhny Novgorod. Sometimes other manufacturers’ trademarks and stamps were counterfeited, but they were quickly exposed. The fake samovars were destroyed and the ashamed manufacturers were fined.

Above: The samovar on the left was made in Tula (1850-90). In the center is a small samovar called tête-à-tête made by the craftsman V. Chekov (the last third of the 19th century). And on the right is a samovar called Bochonok (“little barrel”) made in the Batashev Brothers factory in Tula (1871-85).

Samovars in Russia were first made in the Urals. Although Tula is considered to be the birthplace of samovars, facts show that the town of Suksun in the Urals Mountains was the real place of birth. Documents from 1740 had the first mention of a samovar, a 16-pound, copper-tinned samovar made at the Suksun factory. Historians found the first mention of Tula samovars only in 1746.

Samovars are a pleasure for homes, restaurants and taverns. Judging by the size, it is easy to guess that the samovars pictured below were tavern samovars. The type on the left is called a “smooth jar” (Tula, 1920-40). The samovar in the middle is also from Tula, but it is older and was made by the Persian “Shemarin Brothers Trading House Unlimited,” a supplier to the Shah's Court (1906-17). On the right is a Soviet tavern samovar with tray (1920-40).

And finally, below is a joke samovar for very impatient tavern customers.

A samovar was an expensive purchase. Ordinary peasants wanted something beautiful in their homes, but sometimes they didn't know what to do with it. Dmitry Rostislavov (1809-1877), a Russian writer, professor and inspector of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy, left fascinating descriptions and notes dating back to the 1820s.

“A peasant woman,” he wrote, “either on her own or after consulting with her husband put loose tea right into a cast iron or metal pot with boiling water, but when she saw that the water was still clear, she decided to add buckwheat groats, onions and other seasonings."

We’ll stay traditional. And serve cherry galette for tea.

Cherry Galette

Ingredients

Dough:

- 250 g (8.8 oz or 2 c) flour

- 1 Tbsp sugar

- pinch of salt

- 100 g (3.5 oz or ½ c) cold butter

- 1 egg

- 2 Tbsp cold water

Filling:

- 500 g (1.1 lb or about 2 ¼ c) seeded cherries (can be frozen)

- 1 Tbsp sugar

- 1 Tbsp liquid honey

- 1 Tbsp starch

- 3 Tbsp breadcrumbs or cornflake crumbs

Instructions

- Preheat oven to 180°C/355°F.

- Mix the flour with the sugar and salt.

- Cut the butter into 1-cm (1/2 inch) pieces and knead into the flour mixture with your hands.

- Add the egg and mix.

- Pour in cold water one tablespoon at a time and knead the dough with your hands. The dough should not be crumbly, but not stick to the surface. You will need 2 to 4 tablespoons of water.

- Put the dough in the refrigerator for 25-30 minutes.

- Mix the cherries with the honey, sugar and starch.

- Roll out the dough into a circle 5-6 mm (about ¼ inch) thick.

- Sprinkle breadcrumbs in the middle of the circle, 8 cm (3 inches) from the edge, and spread evenly.

- Put the cherries in a dense layer on the breadcrumbs.

- Fold the edge of the pastry over the filling, pressing it evenly.

- Bake in a preheated oven for 30-40 minutes.

There is no point telling you how long this galette will keep. By the time your children ask if there is any left, it will be long gone.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.