"When you wake up in the morning, Pooh," said Piglet at last, "what's the first thing you say to yourself?"

"What's for breakfast?" said Pooh.

Breakfast is indeed the most important meal of the day. And although breakfast was different in different centuries, it has always — or almost always — played a great role in the daily menu.

The word "breakfast" in Russia has not always been associated with scrambled eggs and a sausage sandwich. In each century it has been different. Perhaps the oldest mention of breakfast is in the “Tale of Igor's Campaign” written in the 12th century. During his flight from captivity by the Polovtsy, Prince Igor (1151-1201) “slayed geese and swans for breakfast, lunch and dinner.” Swan for breakfast? Not even today’s wealthiest oligarch would think of that.

Meanwhile, breakfast in our distant past reflected the country’s social disparities, but at the same time, it brought people of different incomes together. Most people ate porridge left over from the evening before. Sometimes the hostess would rise early and make blinis. It was common to eat soup for breakfast — cabbage soup. Soups weren’t just filling thanks to the broth — after all, there were fasting days, too, with vegetable broths — but for the bread eaten with it. That provided the necessary calories.

This practice survived into the 19th century. People doing hard work have always valued breakfast. For example, the famous Russian vegetable grower Yefim Grachev (1826-1877) hired peasants for work and always served them cabbage soup and bread for breakfast — as much as they wanted. The workers were also served porridge, either oat or millet.

Buckwheat was considered very delicate and quickly digested. And a man needed his stomach to be full longer. "Because of this, a working man is never served kissel [a gelatin made from grain] — it doesn’t fill him up," the famous Russian ethnographer Pavel Nebolsin wrote in 1862.

If you think that the breakfast of a nobleman or landowner, even in the early 18th century, was lighter, you are mistaken. The landowner worked as hard as the peasants, but simply had other “work” — he might ride 15 miles on a hunt, travel around the farm and fields, or flog guilty peasants in the stables. Everything had to be looked after. Sometimes they stayed in the saddle right up to dinner.

What did they have for breakfast? Mostly leftovers from last night's lunch and dinner. Cold pork, roasted meats, pickles, eggs, aspics. Pies and blinis. Before tea became a part of everyday life they drank plain or effervescent kvass (sour drinks are a good hangover cure), a honey drink called sbiten or rich fruit drinks.

The habits of the bygone era seem quaint today, and many breakfast foods are long forgotten. History has preserved the menu served near Tula for breakfast to His Serene Highness Prince Grigory Potemkin:

"Your Lordship, a delicious breakfast has been prepared for you.”

Potemkin looked attentive.

“The Tula brook trout are fresh from the water, and the rolls are still hot. All this is worthy of your lordship's attention.”

The glass in the traveling carriage was lowered.

“The milkcap mushrooms from Tula and sturgeon caviar are worthy of attention, too...”

“Hmmm," replied Potemkin.

“And there are rockfish — large ones, just begging to be eaten.”

“Are they?”

“And on top of that, Your Highness, they'll fry an egg for you in no time.”

“Tell them to open the carriage," shouted the Prince, who was evidently tempted by that last dish.

Potemkin got out of the carriage, stretched himself to his full height, glanced at his half-frozen companions, and said:

“Let's go!"

Things changed near the end of the 18th century, when the lifestyle of the Russian aristocracy became different. There was less physical exertion. The urban daily routine was predictable: work, ministry, assembly, an evening ball. The diet of well-to-do society gradually changed, too: it became lighter and more elegant.

But there was a surprising change, too. "Breakfast in the capital is a cold snack with a shot of vodka," the magazine “Panorama of Petersburg” wrote in 1834. “In the morning whenever they rise, they drink tea or coffee along with some kind of bread (pies or pastries). Between noon and 2 o'clock they have a breakfast of cold dishes with a glass of vodka or wine.” A shot of vodka for breakfast?

All this sounds a little strange today. But it’s easy to understand. In that era there wasn’t just one breakfast. Usually at 8 or 9 a.m. the family sat down for morning tea, or perhaps coffee or hot chocolate. The children had milk with a stale (!) bun and butter. Adults could avail themselves of pastries, cookies and crispbread.

At 11 a.m. or noon a bigger breakfast was served, usually with leftovers from the previous day's lunch and a specially prepared dish that wasn’t very expensive, such as fried potatoes, blinis or baked puddings.

We think of porridge as a simple and plain dish. But it was served in aristocratic households. In Yekaterina Avdeyeva's cookbook, published in the 1840s, we came across Baranov's porridge made from pearl barley. We tried it and liked it. The only problem was we couldn’t figure out who those Baranovs were.

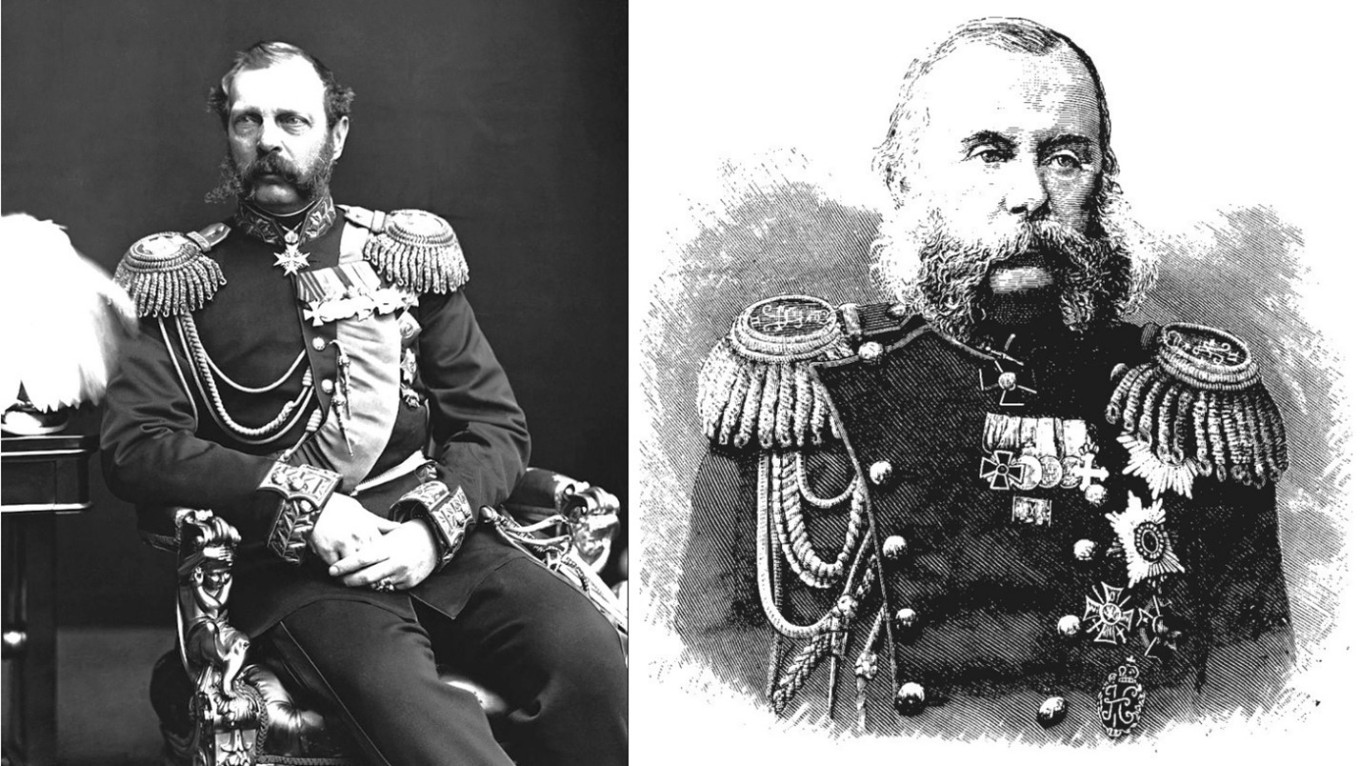

It turns out that Julia von Baranov (née Countess Adlerberg) was the tutor of the little Grand Duke Alexander Nikolayevich, the future Alexander II, and his sisters. She took care to serve them the barley porridge she had known in her childhood on the Estonian estate of her parents, the Adlerbergs. The children grew up but still liked the Baranov porridge of their childhood. Alexander II was close friends with Julia’s son, Count Eduard Baranov, throughout his life, and they continued to enjoy this baked porridge during their hunts in the Pskov forests.

This dish is something between porridge and baked pudding. And for breakfast it's just perfect.

Baranov's Porridge

Ingredients

- 180 g (3/4 c) pearl barley

- 200 ml (half pint) water

- 250 ml (1 c) milk

- 1 Tbsp butter

- 4 eggs

- 100g (1/2 c) high-fat sour cream

- salt to taste

- cream for serving

Instructions

- Rinse the barley thoroughly, then put it in a bowl and cover with cold water.

- Let the barley soak for 3 hours.

- Rinse and drain again.

- Put the barley in a saucepan and cover with the hot water. Cook, covered, until all the water is absorbed —20-25 minutes.

- Heat the milk to boiling and pour into the saucepan with the barley.

- Add half a tablespoon of butter and salt.

- Cook over low heat until the grains are completely softened. The milk will be absorbed almost entirely and the barley will become soft.

- Then mix the eggs and sour cream, add to the porridge and stir in the remaining butter.

- Spread the porridge in a greased baking dish and put it to the preheated oven (180°C/350 °F ). Bake for 45 minutes until the top is browned and crisp.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.