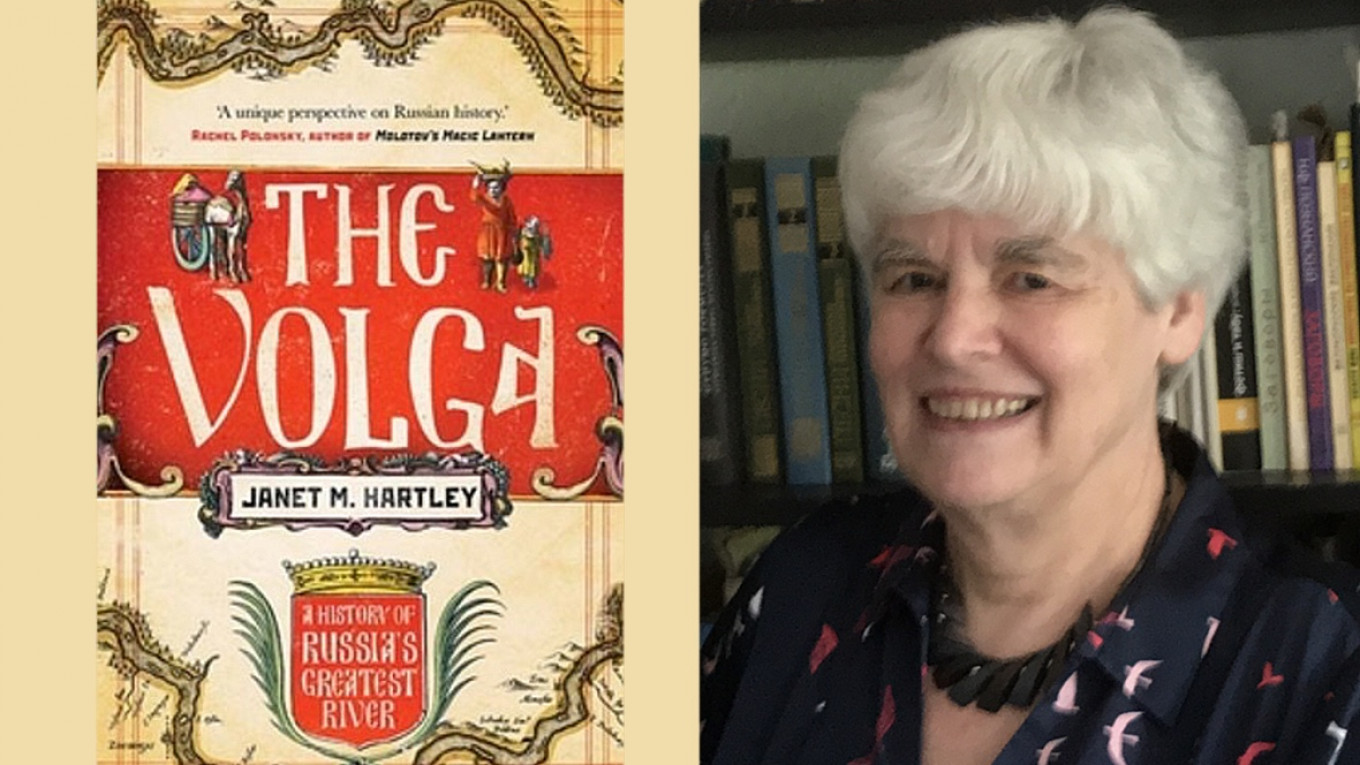

It is impossible to imagine Russia or her history without the Volga, Russia’s — and Europe’s — longest river along whose shores so many of the country’s more pivotal political, economic, and cultural events have taken place. Known as “Mother Volga,” the river has always played an outsized role in the national consciousness. The complex and colorful history of this storied river is the subject of a new book by Professor Janet Hartley, Emeritus Professor of International History at the London School of Economics: “The Volga: A History of Russia’s Greatest River.”

“The Volga” is Professor Hartley’s second exploration of Russian history rooted in a physical entity. Her acclaimed “Siberia: A History of the People” used that vast region to consider the people who settled — or were forced to settle — in a place that served as a vast and inhospitable prison.

Hartley’s deft narrative of the Volga begins with the early 7th century Khazar Khanate, populated by Turkic tribes who are the first recorded beneficiaries of the lucrative North-South trade route of the river. Viking traders known as “The Rus,” or “men who row,” used the Volga to bring furs, slaves, beeswax, honey, and ivory south to the great trading hub at Itil. The Rus were “invited” to rule over the Slavic tribes, and their descendants founded the great medieval fortress towns on the shores of the Volga: Uglich, Yaroslavl, Kostroma, and Tver.

At the opposite end of the Volga where the river empties into the Caspian Sea, the Mongol invaders held sway for two centuries (1240 - 1480) in their great capital of Astrakhan. Resistance to the Mongols, led by the Grand Prince of Moscow, helped to unify the splintered Russian principalities into a nation state. The final sack of Kazan and Astrakhan by Ivan the Terrible in the mid-sixteenth century marked a major turning point in Russia’s history, and that of the Volga.

Hartley touches on these and other major milestones of Russian history throughout the book, but keeps the complex social interaction and development taking place along the Volga front and center in her narrative. She traces the Volga as a boundary of a hinterland, one that attracts brigands, outlaws, and pirates, and foments revolt such as those led by Stenka Razin, Yemelyan Pugachyov, and eventually Vladimir Lenin. Hartley also explores the role of the river as a tangible division of the ever-expanding empire from west to east. Even as Russia becomes a multi-ethnic and multi-confessional state, the Volga provides a barrier between Muslim and Christian, Russian and non-Russian, and opposing armies.

As trade and technology develop in the seventeenth-and eighteenth centuries, the Volga serves as a principal conduit of goods and know-how, supporting the rise of Nizhny Novgorod as a great trading center of the empire. Cultural and political ideas move along the river as well, and as nineteenth-century intellectuals struggle to define a national identity, the mighty Volga offers inspiration, harnessed by musicians, poets, and painters.

Bolshevik propagandists find in the Volga a rich metaphor for the triumph of Soviet technology, which “tamed” the great river, a concept explored by both Ivan the Terrible and Catherine the Great during their encounters with the Volga. Later, the Soviets return to the symbolism of the river as “Mother” during World War II, as the Red Army halts the Nazis on the shores of the Volga, during the carnage of the Battle of Stalingrad.

“The Volga” is an eminently readable book — for both the seasoned historian of Russia and those encountering the vast nation and its colorful history for the first time. In shaping her narrative to the ebb and flow of Russia’s great river, Hartley offers valuable insights into the Russian mindset and hints what may lie in their future. “The Volga” combines outstanding academic research with masterful and compelling storytelling. The result is a memorable journey into the heart of Russian social, political, and cultural history.

From the Introduction to “The Volga: a History of Russia’s Greatest River”

Although the river Volga was never the geographical border between Asia and Europe, in many ways the middle and lower Volga does draw a line between the Christian, Russian, European West and the Islamic and Asiatic East. ‘I am in Asia’, declared Catherine II in a letter to Voltaire from Kazan in 1767. The topography of the land on either side of the middle and lower Volga accentuates this feeling of a divide: the land on the western (right) bank is hillier, more cultivated and richer in vegetation; the land on the eastern (left) bank is low-lying, flat, mostly scrub land, stretching to the borders of Kazakhstan. Certainly, the German settlers who had been encouraged to come to the Volga region by Catherine II in the 1760s felt that those who had been granted land on the western ‘mountain side’ in Saratov province were fortunate – not only because the soil was better than on the eastern ‘meadow’ side, but also because they were not so exposed to dangerous raids by Kalmyk and Nogai horsemen. In their eyes, the river was a dividing line between European civilization and Asian barbarism.

However, the Volga was not simply an east–west, Europe–Asia divide. It was also a meeting place and (to an extent) a melting pot of many different peoples within, first, the multi-ethnic and multi-confessional Russian Empire, and then the Soviet Union. Astrakhan became home to Armenian, Persian and Indian traders, all of whom had their own quarters, religious and trading buildings and their own institutions. Kazan is today a Tatar and a Russian city; the countryside to the north, east and west of Kazan is inhabited by Russians, Turkic and Finno-Ugric peoples. In the Soviet period, autonomous republics were founded for non-Russian peoples in the 1920s within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, and these still exist within the Russian Federation today (with the exception of the short-lived Volga German Autonomous Republic). All the republics, however, contain a significant ethnic Russian population and are important important today for the forging of identities in a new Russia.

The religious composition on the Volga is complex. Finno-Ugric settlers originally followed shamanistic beliefs, although many converted, at least nominally, to Orthodoxy after they became subjects of the Russian Empire. The ruler and the elite in Khazaria probably converted to Judaism sometime in the early ninth century. Kalmyks in the south and south-east of the Volga were Buddhists (the only Buddhists in Europe). The Bolgar state, the Golden Horde and the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan were, or became, Muslim. The Russian and Soviet states were conscious of the potential threat of Islam in the Volga region from the time of the conquest of Kazan in 1552. The history of the Volga is, in part, the history of (often forced) conversion to Orthodoxy by the Russian government and the reaction to this of the local inhabitants. In many cases, the conversion process was incomplete or, in the case of Islam, could be reversed. The remoteness of much of the Volga countryside attracted Old Believers – that is, schismatics from the Russian Orthodox Church who did not accept the changes in liturgy and practice in the middle of the seventeenth century. Eighteenth-century German settlers could be Catholic or Protestant. Settlements on the river Volga were a microcosm of the ethnic and cultural complexity of the Russian Empire and the Soviet state, and this study will examine the relationships between different groups of people on the Volga, and between non-Russians and the government.

The river Volga played a key role in the creation and evolution of early ‘states’, the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The importance of trade and strategic access to the Volga and the Caspian Sea led to rivalry and conflict between Khazaria and the Bolgars and Kievan Rus; and then between the Golden Horde (and its successor khanate in Kazan) and Moscow and other Rus principalities in what is now European Russia. After the conquest of Kazan and Astrakhan, the tsars of Russia took the title ‘tsar of Kazan and Astrakhan’ (and Siberia), as well as ‘tsar of all Russia’. From this time on, Russia can be considered an ‘empire’, although the western title of ‘emperor’, rather than tsar, was only taken by Peter I in 1721. The middle and lower Volga regions were the first significant non-Russian and non-Christian lands where the Russian Empire had to establish and exercise control. In many ways, they provided a testing ground, and then a model, for imperial (and to an extent Soviet) policies towards non-Russian peoples.

The major Cossack revolts of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were in effect Volga revolts, as the rebel armies of Stenka Razin and Emelian Pugachev sailed up and down the river and sacked important Volga towns. Settlements on both banks of the Volga were ransacked by nomadic nomadic tribesmen from the east and the south. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the region was beset by rural and urban resistance and revolt. The imperial government and the Soviet state responded by suppressing rebellious subjects and strengthening their administrative control, but also by intensifying their cultural and educational presence in the region. Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union were to an extent shaped by the experiences of ruling over lands acquired in the sixteenth century on the Volga.

The Volga became a crucial point of conflict in the twentieth century, and was central to the establishment and survival of the Soviet state. The river, and several key Volga towns, played a crucial role in determining the outcome of the Russian Civil War in 1918–22. Samara became, briefly, the centre of resistance to the new Soviet state, and towns on the middle and lower Volga were of vital strategic significance for both Whites and Reds. The failure of the White armies to join up on the river Volga largely determined the outcome of the Civil War. In the Second World War, the battle of Stalingrad was pivotal in the defeat of the German army and the survival of the Soviet Union. Both at the time and since it has been projected as the greatest of all ‘patriotic’ sacrifices made by the Soviet people. The river Volga at Stalingrad was regarded in 1942–43 as the key boundary, the Rubicon, which the Germans must not cross. Part of the enormous memorial complex of the battle shows German soldiers only crossing the river as defeated and demoralized prisoners of war.

Finally, the Volga became the subject of poetry, literature and art, and helped shape a sense of Russian identity through a shared experience of the river. Late-eighteenth-century odes to Catherine II both glorified the river and also ‘tamed’ it to honour the ruler. In the nineteenth century, writers, artists and tourists fully ‘discovered’ the Volga as something unique and special to Russia and all Russians. The Volga became ‘Mother Volga’ and the protector of the Russian people. The ‘gloomy grandeur’ of the Volga, as Bremner put it in the opening quotation of this chapter, was also, however, a common theme in Russian poetry, literature and art. The famous painting by Ilia Repin, Barge Haulers on the Volga, uses this image to depict the exploitation and suffering of ordinary people in late tsarist Russia. The battle of Stalingrad reinforced the special importance of the river as a barrier that protected the Soviet state and all its people, Russian and non-Russian, from those who wished to destroy them, and this was reflected in contemporary poems and popular songs.

The change from regarding the river as the border with the ‘other’ (Asia) to adopting it as a symbol of Russianness within Russia is in part a reflection of the evolution of a Russian identity, in which the Volga played a significant part. However, it is also the river of many non-Russian peoples, and features in poetry and prose by non-Russians, as well as by Russians. The Volga today plays as important a part in the identification of Tatars in Tatarstan as ‘Volga Tatars’ and as descendants of the Bolgar state, as it does in Russian identity.

The river is of crucial importance to all those who live on its banks, but also to the Russians and non-ethnic Russians who have lived within the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The river, in the words of the popular ‘Song of the Volga’ in the 1938 film Volga, Volga, was:

Mighty with water like the sea,

And just as our motherland – free.

Excerpted from “The Volga: a History of Russia’s Greatest River” by Janet M. Hartley, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2021 Janet M. Hartley. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Footnotes have been removed to ease reading.

For more information about Janet M. Hartley and her book, see her publisher’s site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.