“Great power competitors, namely China and Russia, are rapidly expanding their financial and political influence across Africa,” John Bolton, U.S. President Donald Trump’s then national security advisor, said at a presentation of the White House’s Africa strategy in 2018. Now, Washington’s entire Africa strategy is devised as a reaction to the “predatory practices” on the continent of Beijing and Moscow, which have been automatically lumped together on the same side of the barricades.

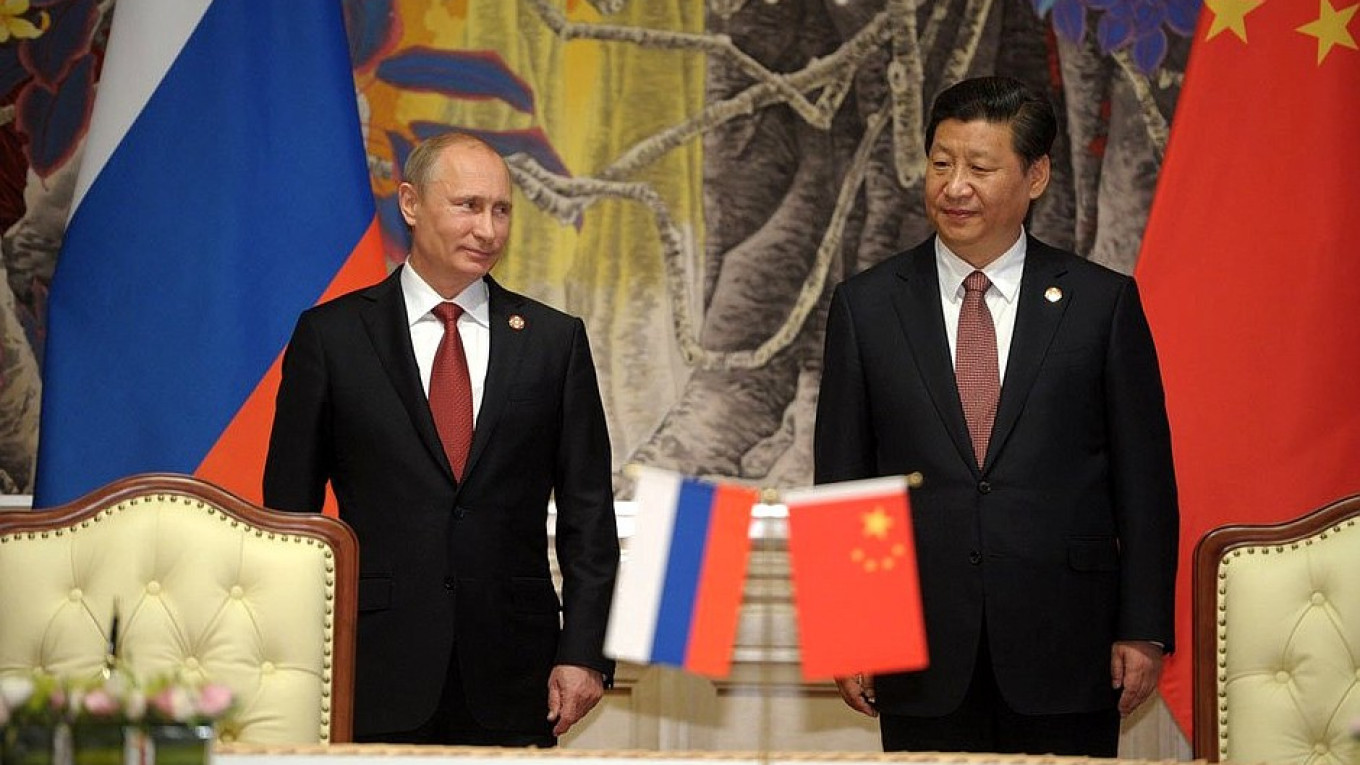

The geopolitical rapprochement of Russia and China is aiding cooperation between the two countries in a part of the world where the presence of Western players has noticeably decreased in the last fifteen years. Chinese penetration of the continent has consistently developed since the start of the 2000s in both bilateral and multilateral formats, while Russia’s influence in Africa only began to manifest itself a few years ago. For now, the appearance of Russia in African countries that are not the continent’s most stable is in China’s interests: Beijing has not yet determined how much effort, money, and time it is prepared to invest in solving African countries’ internal problems.

Much of what China does in Africa falls within the framework of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), an event held every three years since the early 2000s and attended by the leaders of nearly every African country and by the Chinese leadership. Since the mid-2000s, no FOCAC summit has taken place without the announcement of new financing from Beijing for African countries. This support grew from $5 billion in 2006 to $40 billion in 2015. At the FOCAC summit in September 2018 in Beijing, Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced a new package of financing worth $60 billion: $50 billion from Chinese development institutions, and another $10 billion in investment from private companies.

For many years, China has been Africa’s number one trade partner: 17.5% of all imports to African countries come from China (mainly electronics, manufacturing equipment, and metallurgy products). China, for its part, mostly buys raw materials from Africa: hydrocarbons and precious metals and stones.

As Western business has gradually left the continent, China has also become a prominent investor. In the last five years, Chinese investment in Africa has increased by $24 billion, investment from the United States and the United Kingdom has hardly changed, and French investment has decreased by $3 billion.

Beijing’s increased financial presence in African countries worries the West, which believes that Chinese companies and development institutions are putting money into unstable political regimes there in order to gain additional profits. Yet China is only the fourth biggest investor in Africa, having put in $40 billion in 2016, after the United States ($57 billion), the UK ($55 billion), and France ($49 billion). Chinese investment in Africa is primarily in countries that are rich in natural resources, which actually have relatively stable political regimes, and which are China’s leading trade partners in Africa. As of 2017, China had invested the most in South Africa (a total of $6.3 billion), Zambia ($2.5 billion), and Nigeria ($2.3 billion). These countries are also the continent’s biggest recipients of foreign investment from other countries and international institutions.

Hot on the heels of economic penetration, in recent years there has been a gradual increase in the presence of Chinese soldiers in Africa. In 2017, China’s first military base abroad was established in Djibouti, though Chinese officials refer to it as a “logistics complex.” China is also redeveloping Djibouti’s infrastructure, building a railway to neighboring Ethiopia, a water supply system, and social infrastructure.

Even before the appearance of the military base in Djibouti, China had already ventured into the role of a “responsible player” in Africa. When civil war broke out in 2013 in South Sudan — where Chinese energy companies are active — Beijing, under pressure from the international community, acted as a mediator in the conflict: one of its first experiences in officially intervening in another country’s internal political processes.

Nearly a year after Bolton’s speech, the Russia-Africa summit took place in the Russian city of Sochi on October 23–24: the first of its kind in Russia. Since Soviet times, when the Soviet Union provided “brotherly African republics” with diverse economic, humanitarian, and military aid, Moscow’s interaction with African countries has drastically decreased.

From an economic viewpoint, Russia isn’t a serious partner for the continent’s countries. Its trade turnover with nations in Sub-Saharan Africa stood at $3 billion in 2017, in no way comparable with the scale of trade with the United States ($27 billion) or China ($56 billion). Nevertheless, Moscow is currently using all available economic instruments to boost its prestige in Africa: at the forum in Sochi, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the writing off of $20 billion in debt owed by African countries.

Russia’s main export to Africa is arms. Since 2009, Russian arms have officially been sent to eighteen countries there, primarily Angola, Nigeria, and Sudan. In addition to arms deliveries, Moscow exerts influence in Africa via military specialists and advisers. Recently, for example, Russia signed an agreement on military cooperation with the Central African Republic (CAR), which has long been ravaged by civil war. Under the terms of the agreement, military advisers from Russia officially work in the capital Bangui, where CAR’s official government is based. There is also information that representatives of the private Russian military company Wagner are working in CAR as the personal security detail for the republic’s president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra.

Interestingly, it seems that Moscow has ties not only to Bangui, but also to the Séléka alliance of rebel militia groups in the north of the country that are creating headaches for Chinese energy companies that own oil deposits there.

For now, cooperation between China and Russia in Africa mainly comes down to Moscow and Beijing taking similar positions during voting at the UN on issues of the organization’s work in several African countries. This primarily concerns peacekeeping operations on the continent in troubled areas such as the Central African Republic and South Sudan.

Still, the scale of Russia and China’s involvement in Africa is hard to compare. Beijing is one of the most prominent investors and trade partners of the continent, and is gradually getting involved in the resolution of local conflicts and in maintaining stability. Moscow, after a twenty-five-year absence from the continent, is trying to exploit the legacy of its Soviet past, and is using the windows of opportunities that are opening up to send arms and military advisers to areas where Western players and China are not lending enough support.

The geopolitical rapprochement and relatively high level of trust between Moscow and Beijing creates the impression that they are working together in Africa. So far, there is no evidence of that. Russia cannot compete with China in terms of the scale of its influence in Africa, and Moscow’s efforts to make inroads there do not alarm Beijing. However, as it asserts itself as the major power in Africa, China will have to deal with the domestic problems of African countries, and Moscow’s dual influence (such as selling weapons to different sides of a conflict in the same country) could become an impediment to stabilization in the region.

This article was first published by Carnegie Moscow Center.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.