The first “shelter for drunks” opened its doors in November 1902 in Tula, south of Moscow. Funded by the city and staffed by a paramedic and a coachman, it had one assignment: to reduce mortality rates among workers who were drinking excessively.

Fast forward 116 years and this clarity of purpose no longer exists. Drunk tanks are no longer regulated by the state and have long been seen as a signature mark of the repressive Soviet system.

Despite their reputation, there are plans to revive drunk tanks in the 11 Russian cities hosting the World Cup this summer — and the plans appear to be enjoying rare popular support. While federal authorities have yet to decide how the new facilities will work, some regions have revived drunk tanks independently from Moscow.

Samara was the first to begin preparing for heavy-drinking fans.The city has gone as far as to build a new facility close to the stadium so that drunk fans can easily be carted there. Another drunk tank in Samara has already been up and running for three years.

The Russian business daily Kommersant toured the facility in November to see how it works.

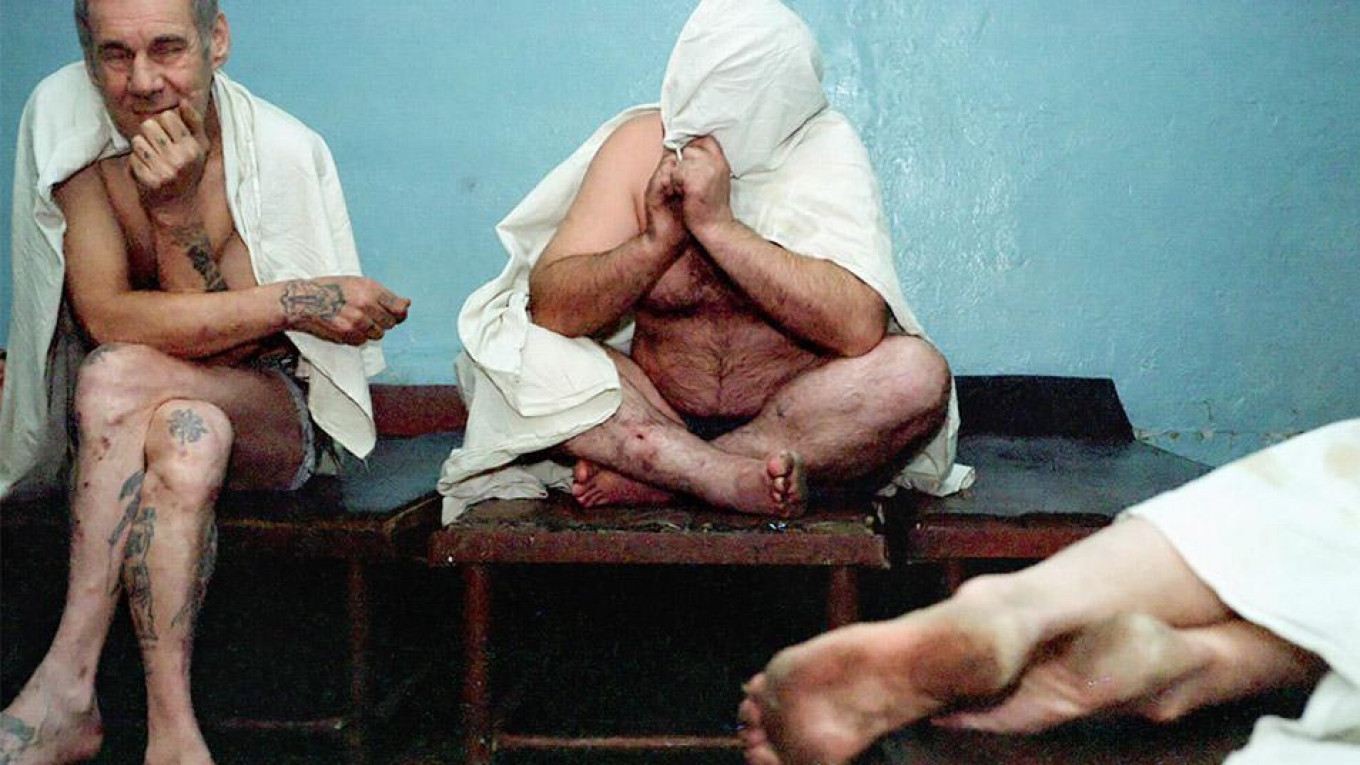

A newly admitted patient is being questioned by doctors, and it isn’t going well. The elderly man in a torn shirt is answering each question with: “That’s right.” The doctor on duty, Alexei Katin, is trying to decide whether to keep the drunk tank’s only lodger for the night.

The history of the man's ailment is short. An ambulance picked him up without ID from the street at 6 p.m. Before passing out, the man just about managed to identify himself as Leonid Ivanovich, the rocket scientist.

Apart from that, it’s been impossible to get any information out of him. The doctor leaves and Natalia Fyodorovna, a nurse, puts the rocket builder to bed: “You’ll sober up, Leonid Ivanovich. Then you can go make rockets.”

This elderly woman in glasses and pink socks is a key employee at the drunk tank. She carries water, helps patients reach the bathroom, changes clothes, makes the beds and washes the floors.

Natalia Fyodorovna used to work as a supervisor at a car park — she only got the new job after she had already retired. “They are ill,” she says of the patients sympathetically. “Sometimes they act like hooligans or call us names, but we don’t listen.”

Then, addressing the rocket scientist affectionately: “You’re not in a hospital. You are in a drunk tank.”

In many ways, however, the facility does resemble a hospital, with its light-colored linoleum, six beds with iron headboards, plastic-coated mattresses and cheap, but new linen with a lilac pattern. There are no bars on the windows or locks on the doors.

Only the smell, which lingers even when the windows are open, hints at the facility's purpose.

Officially, there are no state-run drunk tanks. But the government does fund clinics that test whether or not someone is intoxicated. In practice, this means that Samara’s drunk tanks are registered as government-run medical testing points. The overnight stay is a free bonus.

The facilities are typically located on hospital grounds — in this case the Semashko hospital — and fall under the jurisdiction of the regional narcotics oversight service.

Some of the people who end up there have been picked up off the street, others include drunk drivers or anyone detained for hooliganism or prostitution. Bus drivers also come in to do quick tests before starting their routes — just in case.

In general, the drunk tank is calm and most patients come in before 10 p.m. — People drink at all hours of the day, but there are fewer compassionate citizens ready to call an ambulance for someone who passes out on a street in the middle of the night.

A typical patient

An ambulance stops outside and a grey-haired man in a warm jacket, but with no socks or shoes is rolled out on a stretcher. He is brought into the waiting room for examination and a cardiogram.

“I only drink at home,” he cries out. “Give me the full treatment. Clean my blood. All my blood is drunk!”

The hospital guard walks around the stretcher, swearing.

“And what if the ambulance is not able to get to somebody because of you, you drunk? If only there wasn't a camera here, I would cure you in an instant!"

The patient’s name is Anatoly Vasilyevich. He alternates between calling everyone “Sir” and cursing rudely — friendly one moment and angry the next. He refuses to breathe into the tube.

Dr. Katin calls the police. After seeing their uniforms, Vasilyevich is happy to abide. His daughter’s phone number is found on a keyring that resembles a dog collar along with the keys to his apartment. She does not pick up. Apparently, she is used to dad’s drunken escapades.

The policemen help put grey tracksuit bottoms on Vasilyevich — The drunk tank has an entire store of worn clothes and shoes sent regularly from the nearby Iversky monastery.

A police officer fills out paperwork for the two men for public drunkenness. Since there were no official witnesses when the men were picked up off the street, the policemen cite them for being intoxicated at the drunk tank itself. “This is also a public place,” explains one of the policemen.

A senior police official with a mustache says he preferred the old drunk tanks, run by the Interior Ministry. “It was easier then. You brought them in, handed them over, they were helped into bed.”

“And now all these questions,” he says. “Would you prefer to sleep? Do you want to stay or not?”

In the morning Anatoly Vasilyevich begins to act up again and is hauled off to the police station. Leonid Ivanovich, meanwhile, has slept off his drunkenness, repented, asked for treatment and was then sent to a rehabilitation center with an escort.

Drunks are not allowed to leave by themselves to seek treatment in case they start drinking or lose the will en route.

Open doors

In 2011, Russia abolished the Interior Ministry's official drunk tanks. But only three years later, in October 2014, the first new facilities opened in Samara and in nearby Tolyatti.

Staff from the old drunk tanks were not hired back after authorities in the region decided that the new institutions should function “according to humane standards.”

“We don’t keep people here by force. A person can always get up and leave,” Zhanna Kisilyova, the head of the drunk tank on the Semashko hospital grounds, says.

Before, people were not allowed to check themselves out of the Soviet drunk tanks. Sometimes, “out of habit, people still escape through the windows,” she says. “In April a man broke the mosquito net covering the windows. And before doing that he ate all the food from the fridge.”

At first, the drunk tank even had a comments and suggestions book. In shaky writing, patients would thank the staff for “taking me out of my drunk state.” They would make promises to quit. One resident wrote: “I had a good time here.”

“He was so friendly, so talkative,” Kisilyova recalls. “He helped turn over the patients. And in the morning, he left on shaky legs. We looked under the pillow and there were two empty bottles.”

“After that we started checking everyone’s pockets.”

Technically, no one is fined for being sent to a drunk tank. But patients do have to police pay fines for public drunkenness. When a person is admitted to the drunk tank, staff call the police and they in turn fill out a report for public drunkenness.

In the morning, the patient is taken to a police station where he is kept until the local magistrates’ court ruling. They don’t have to go to the police station if earlier they have asked to be taken to a rehabilitation center for treatment. Either way, they still have to pay the fine. All patients are entered into a special risk database.

“If this person comes, let’s say, to get a gun license, he will be examined for chronic alcohol use,” says Andrei Scherban, the doctor who oversees the Samara region's drunk tanks.

There are no police officers assigned specifically to the drunk tanks. In the months after the facilities restarted three years ago, officers were posted to the drunk tanks, but from the start of 2015, they disappeared.

“When the initiative to revive drunk tanks resurfaced, it was assumed that each site would have a police officer on duty,” says Scherban. “But then [the police] refused. They said it wasn’t their job.”

“The only thing that we managed to agree on after our disputes was that they immediately answer our calls.”

“They now report the number of calls they get to their superiors every month. And their superiors call us once a week to check those reports,” says Kisilyova.

The cell phone numbers of all police patrol cars are written down under a large sheet of glass on the reception desk. But Scherban wants to solve the problem once and for all by hiring security guards at drunk tanks.

Alcoholics’ wives would also like drunk tanks handed back their former powers, staff say.

“Sometimes women call and say, ‘My husband is drunk again, help.’ But we can’t come and take them,” says Kisilyova. “We can’t even put in an IV to take out the alcohol. We are not a medical institution. They just sleep it off here.”

Drunk fans

There are a total of six drunk tanks in the Samara region, including three in the city itself and one each in nearby Novokuibyshevsk, Tolyatti and Syzran. In 2016, 2,463 people were admitted to the six facilities, which is approximately one person per day in each of the six facilities.

Occupancy during the Soviet period was higher, doctors in Samara recall, and there were more institutions then — there were more than 1,000 drunk tanks in Russia during the 1990s.

Could it really be that people have started drinking less? It seems that the reason for those decreasing numbers lies elsewhere. Now that the drunk tanks are no longer under the Interior Ministry's control, only severe cases are treated. In Samara, the average patient is around 40 years old and drunk on moonshine.

Samara also has another drunk tank where hardly anybody is admitted. It is on the city’s outskirts, in hospital No. 7. It was built there in anticipation of the 2018 World Cup. “It will be the most convenient place to bring people from the Samara-Arena stadium,” Scherban, the head doctor, explains.

With fans expected to gather in just two locations in the city, Samara’s doctors have already figured out logistics for the football tournament.

Fans who are picked up at the stadium will be taken to the drunk tank at hospital No. 7 and those at the fan zone on Kuibyshev Square will be taken to hospital No. 2.

The regional branch of the Health Ministry has carefully studied the experience of its colleagues in Kazan during the Confederations Cup, which took place in the Tatarstan capital in June 2017. The numbers admitted to the local drunk tank grew by 150 percent.

The Health Ministry has even warned doctors over “matches that pose an increased challenge.” These are games in which England, Germany and Belgium will play. And although none of these teams are playing in Samara during the group stage, the city will host the most anticipated match for Russia, against Uruguay, on June 25.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.