Russian fans couldn’t wait for the official release. “My patience only lasted for two days,” says Anna, an experienced gamer and a longtime admirer of Pokemon.

Like tens of thousands of other Russian smartphone users, Anna decided to download the unreleased app using an account set up in a foreign App Store. “The fact that it was sort of illegal and Apple could ban me for it didn’t stop me,” she said.

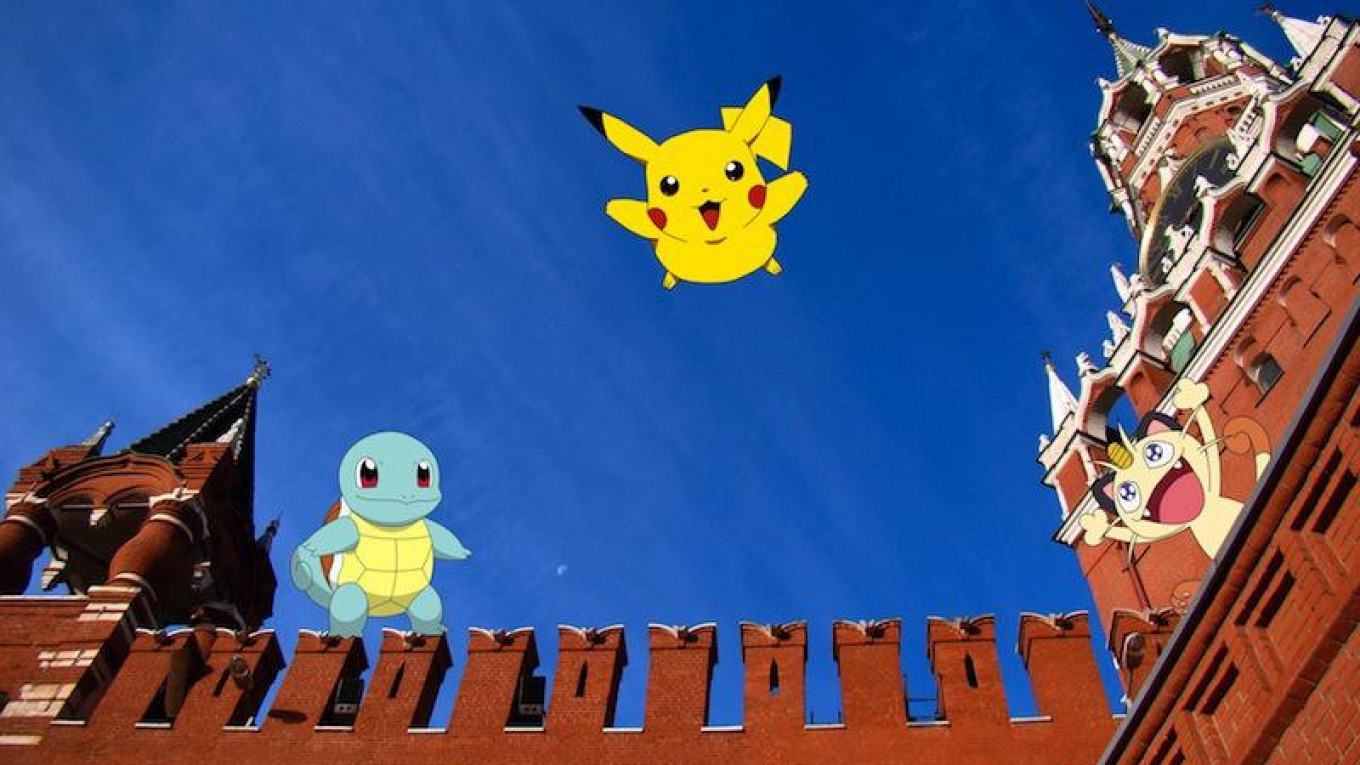

“Pokemon Go,” the latest online game by Nintendo, went viral in a matter of days after it was released in the United States, Australia and New Zealand on July 6. With its interface placing cartoon creatures on actual landscapes captured by a smartphone camera, “Pokemon Go” is said to have created a new reality — one that connects a virtual world with the real one.

In Russia, the game has stumbled upon a different reality: bans, criticism from traditionalist forces and threats of criminal prosecution.

Russian officials have already condemned Pokemon as “dangerous” and “eroding morale.” Several patriotic organizations have called for a ban. State-owned television channel Rossiya 24 aired an entire report explaining how Russians could be committing criminal offenses while playing it.

Businessmen, meanwhile, ignored the above, and decided to ride the Pokemon wave.

Restricting the Devil

Nintendo refuses to reveal when the game will be released in Russia. But Russia’s traditional values crusaders are already worried nonetheless. “It feels like the devil arrived through [Pokemon] and is trying to tear our morality apart from the inside,” said Frants Klintsevich, a senator of the Federation Council, Russia’s upper chamber of parliament. Klintsevich has called for a list of “restricting measures” to help gamers avoid falling under Pokemon’s corrupting influence.

He was not alone in calling Pokemon demonic. A nationalist, ultraconservative Cossack group based in St. Petersburg, Irbis, announced plans to appeal to consumer rights watchdog Rospotrebnadzor, the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service and Apple to ban the game in Russia, using the same comparison. “We need to take people out of the virtual world, and this generally smacks of Satan,” said Andrei Polyakov, the group’s leader.

The Russian government’s Communications Minister Nikolai Nikiforov took a more reasonable stance. He doesn’t see the need to ban the game, he said. That did not stop him preferring a conspiracy theory of his own.

“I’m starting to suspect that intelligence services might have contributed to this app,” he said. Perhaps this was to “collect video-information” about different locations around the world, the minister said.

Several other concerned officials called for restricting players from hunting Pokemon at specific locations, including churches, cemeteries, military areas or in government institutions. “A game like this should definitely have location restrictions,” said Yana Lantratova, a member of the Presidential Council for Human Rights.

The media storm peaked when Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov decided to address the “Pokemon Go” question. Peskov was asked whether the Presidential Administration would object to people catching Pokemon in the Kremlin; he said that the Kremlin was “unprecedentedly open,” but added that catching Pokemon should not be the only reason to visit the “treasury of worldly culture.”

Behind Augmented Reality

“Pokemon Go” is not the first game based on augmented reality, says Alexander Kuzmenko, head of the Games Mail.Ru project. Five years ago, the creators of “Pokemon Go” released a similar game, “Ingress” — but it was too complicated, with numerous rules and teams. “Pokemon is simple and clear: you find them, you collect them and then you make them fight one another,” Kuzmenko says.

“Ingress” and its augmented reality came out ahead of time, he adds. Creators of “Pokemon Go” used the same technology, and it exploded. “Unprecedented popularity of the Pokemon franchise contributed to the success a great deal,” Kuzmenko says. “It was hugely popular back in the day, and now the generation of people who were fans of Pokemon [as children] are playing it because they’re nostalgic.”

Kuzmenko is positive that the game is the first harbinger of augmented reality becoming part of everyday life. “Imagine all the ways it could be used,” he says. “Just off the top of my head, you would be able to walk around a city, capture buildings and monuments with your camera and immediately see information about them. The game industry has always been on top of technology, and new useful inventions will definitely follow.”

Speaking to The Moscow Times, child psychologist Anton Sorin insisted there was nothing dangerous about the game. Indeed, it might, perhaps, encourage teenagers to leave their computers and explore the world. “Cossacks and Orthodox activists adamantly resist it simply because it is an idea that unites people — just like their own ideologies, and they don’t want Pokemon to steal their potential audience,” says Sorin.

Nothing Personal, Just Business

While officials make headlines by vocalizing their concern about the game, Russian businesses have already begun to develop marketing schemes using “Pokemon Go.”

Russia’s state-owned banking giant, Sberbank, announced on Monday that it would launch “Pokestops” — areas containing many Pokemon — near its offices and offer players free accident insurance. Another state-owned bank, VTB24, promised to double cash-back for those who took a photo of a Pokemon and a VTB bank card. Russia’s biggest luxury department store, TsUM, offered to add 500 bonus points to a shopper’s discount card for every Pokemon caught inside the store.

“Pokemon Go” might also be used as a political tool, suggests Vladimir Petrov, a lawmaker from the Leningrad region. If app creators could place rare Pokemon in polling stations during upcoming elections, more youth votes could be gathered, he suggested on Sunday.

In the meantime, Russians’ interest in the game grows by the day. So far, Russians have searched for information related to it more than 1.7 million times, spokespeople of the biggest Russian search engine Yandex told The Moscow Times. This is 50 times more than every other Pokemon-related search in recent years.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.