Of all the many things I love about Russian — right up there with the fun of studying grammar, learning spelling rules, and memorizing irregular verb conjugations — is etymology: tracing a word from its origins to its present meaning and usage. Suddenly a word that made no sense becomes transparent, or a concept is rounded out with layers of meaning from the past.

Take a phrase that I never quite understood — в опале. It means being out of favor, usually politically but sometimes figuratively. You could say, only partially in jest: Не сказав жене, муж купил мерседес. Он теперь в опале. (Without telling his wife, a man bought a Mercedes. Now he's in the dog house.) But where does this strange phrase come from?

The key is when the word appeared in Russian — in the Muscovy period before Peter the Great. It was then that English merchants appeared in Moscow, and among the first presents the English traders brought the tsar were opals. Opals are strange stones; they have such high water content that they are considered "amorphous," and if not properly cared for, can turn milky and lose their value. The Russians borrowed the English word "opal" for the expression "в опале," that is, like a milky opal, worthless, out of favor with the tsar.

Another interesting case is the mystery of the verbs сесть (to sit down) and съесть (to eat), the bane of Russian language students, who have to remember which verb gets the hard sign. For many years I thought it was purely coincidental that the verbs were so similar. But it turns out that they came from the same original verb. In old Russian — and old Russia — life was an endless round of work, and people were on their feet all day. The only time they paused to sit down was at mealtime. So "to sit" began to acquire a second meaning of "to sit and eat," which over time morphed into "to eat." The hard sign was put in to distinguish the verbs from one another.

And while we're on the subject of eating — have you ever wondered about the word кушать (to eat)? At some time or other you've probably been scolded by someone in the older generation for using кушать in reference to people. You'll be told: Кушают только свиньи, люди едят (Only pigs feed; people eat.) Apparently, the verb кушать is derived from the Russian word for corn, кукуруза — the letters к and ш often alternate — and corn was first imported and then grown solely as fodder for livestock. So кушать carries echoes of pigs slurping down corn mash at the trough, and hence is not the verb to use for a dinner party.

And then there's an interesting story about another word commonly used around the kitchen — ужин (dinner). Ужин is both the evening meal and the food served at it. In Russia, as in many other countries, the biggest meal of the day was eaten mid-day. This was often a huge meal with soup and several meat courses, which got the name обед as a short form of О! Беда! (Oh! How terrible!). Ужин was уже — more narrow, a lighter meal before retiring.

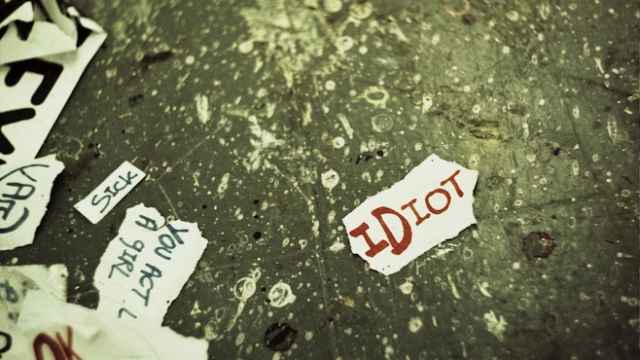

And finally, one other interesting phrase: С днём дурака! (April Fool's Day!). Not a single word of this was true — except for the bit about loving grammar.

Michele A. Berdy, a Moscow-based translator and interpreter, is author of "The Russian Word's Worth" (Glas), a collection of her columns.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.