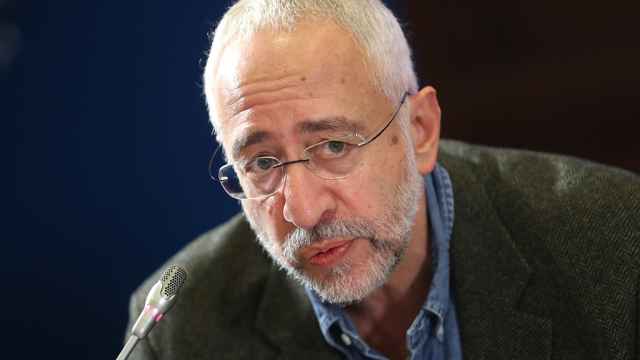

Yesterday, Derk Sauer, founder of The Moscow Times, passed away. He left us too soon, at just 72 years old, full of energy and ideas.

Derk was a remarkable man. Those lucky enough to work with him or even just cross paths with him knew this while he was still alive, and it will become even clearer now that we have lost him.

I spent hours working on this column. Not because I struggled to find the right words, but because messages of condolence kept pouring in from friends and strangers alike. Here is the latest: “Sauer was a pluralist who was ahead of his time and created real Russian journalism in the Russian Federation. He knew what he was doing. And he planted the seeds of future freedom. He worked long and hard, and we read his publications. The Moscow Times is the greatest fruit of his labor.”

Derk was a real star in the Netherlands — a leading expert on Russia, a successful entrepreneur, a patron and a mentor. But he meant even more to Russia. Derk achieved the extraordinary: not just building a successful business in another country, but creating an entire industry — the modern Russian print media market — and an entire institution — that of quality, independent journalism. As a bonus, Derk, his wife Ellen Verbeek and their partners created Russia’s glossy magazine culture — something that hadn’t existed in the Soviet Union at all.

From the time of the first Russian newspaper created by Peter the Great until the Soviet collapse, Russian media was primarily a propaganda tool. There was no real distinction between news and opinion; journalists would first report what happened, then explain why it was good or bad. With the launch of The Moscow Times in 1992, Derk brought real journalistic standards to Russia: separating news from opinion, requiring two independent sources for news, and so on. At first, the newsroom was made up of only expats. But very soon after, Derk opened a training school for Russian journalists right inside the paper.

I started working with Derk in 1995: first at The Moscow Times, at Kapital, at Vedomosti — the globally unique business project which Derk co-founded alongside The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times — at VTimes and again at The Moscow Times. At least three of these projects have already earned their place in the history of Russian and global journalism.

After meeting Derk, I learned the difference between a businessman and an entrepreneur: a businessman makes money, while an entrepreneur creates public good and profits from it. “Profit is not the goal of a business decision, but confirmation that it was the right one,” said another remarkable entrepreneur, Isador Sharp, founder of the Four Seasons hotels. Derk embodied that idea throughout his life.

Now, after living in the Netherlands for three years, I understand that Derk was a true Dutchman, even though he spent almost half his life in Russia. Like a true Dutchman, Derk was not afraid to move to a completely unfamiliar country with his young wife and infant son. He wanted to bring his knowledge to this country and learn something new for himself. And yes, to build a successful business, if possible. For the Dutch, prosperity isn’t something to be ashamed of — it’s a virtue.

The Moscow Times became the foundation for Independent Media, which would go on to become Russia's largest publishing house. Years later, when Derk sold the company to international publishing groups in two stages, he shared the proceeds with his entire staff, from drivers to directors — first $1 million and then $2.7 million. This wasn’t some pre-arranged deal. There were no contracts, no promised stock options. “For me, there was no question of whether or not to share with the employees,” Derk told me of the logic behind his decision. “Because these people made us rich — it wasn't me who made these newspapers and magazines every day, it was them. I proposed it to my partners, and they immediately agreed.”

Independent Media's motto was “Inform and Inspire.” I think that was Derk's personal motto, too. A journalist to the core — principled and, when necessary, firm and uncompromising — Derk was also an excellent mentor who trained hundreds of managers, businesspeople and entrepreneurs. He believed that any good leader has four main tasks: to protect their team from distractions so they can do their best work; to inspire them; to guide and teach when needed; and to supervise them. Thousands passed through Independent Media and became true professionals — not only journalists, but also marketers, salespeople, designers and managers who carried the knowledge and values they gained at Independent Media with them.

For many, many people, including myself, meeting Derk changed the course of our lives. We remember and will always remember Derk with endless gratitude and respect. A colleague, with whom I started working at The Moscow Times in the 1990s and whose family has long lived in Europe, wrote to me: "I came to The Moscow Times as a mathematician looking to practice English, and a few years later I left as a journalist. I think my love for The Moscow Times largely inspired my daughter to choose journalism as a profession. So really, our whole family has been shaped by it."

Derk was not an idealist. He knew that life was unfair. But he had ideals and values, and he always stood by them, trying to make life fairer and better, at least for those he could reach. And he succeeded.

Derk could have stopped working long ago and enjoyed the life he built. But work — new ideas, new projects, new challenges — was his life. Derk was ready to get involved in solving problems, no matter the time or place. He also enjoyed yachting, cycling, skating and skiing, all at a professional level. But above all, Derk lived for his family. Everything Derk did in his life, he did first and foremost for them, like a real man. And his family was exemplary: 40 years of happy marriage, three wonderful sons, two granddaughters whom Derk adored…

In the last three years of his life, Derk faced a new challenge: to save the school of Russian journalism he had helped build. After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, hundreds of Russian journalists refused to compromise with Putin's regime. They chose exile over censorship, continuing to report the truth from abroad.

The material and non-material resources that Derk was able to raise helped The Moscow Times, Dozhd, Meduza and other media outlets survive in exile. Professional journalism is a school where working principles and standards are passed down from one reporter to another. If that chain is broken, if that school disappears, Russia will have to wait for another Derk — someone willing to spend decades building it back from scratch. But the flame that Derk lit more than 30 years ago has not been extinguished. And we will bring it back to Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.