My middle name is Learmont, and I am one of the few surviving members of the Scottish family that provided Russia with one of its greatest lyric poets, Mikhail Lermontov. Let me tell you how it all came about.

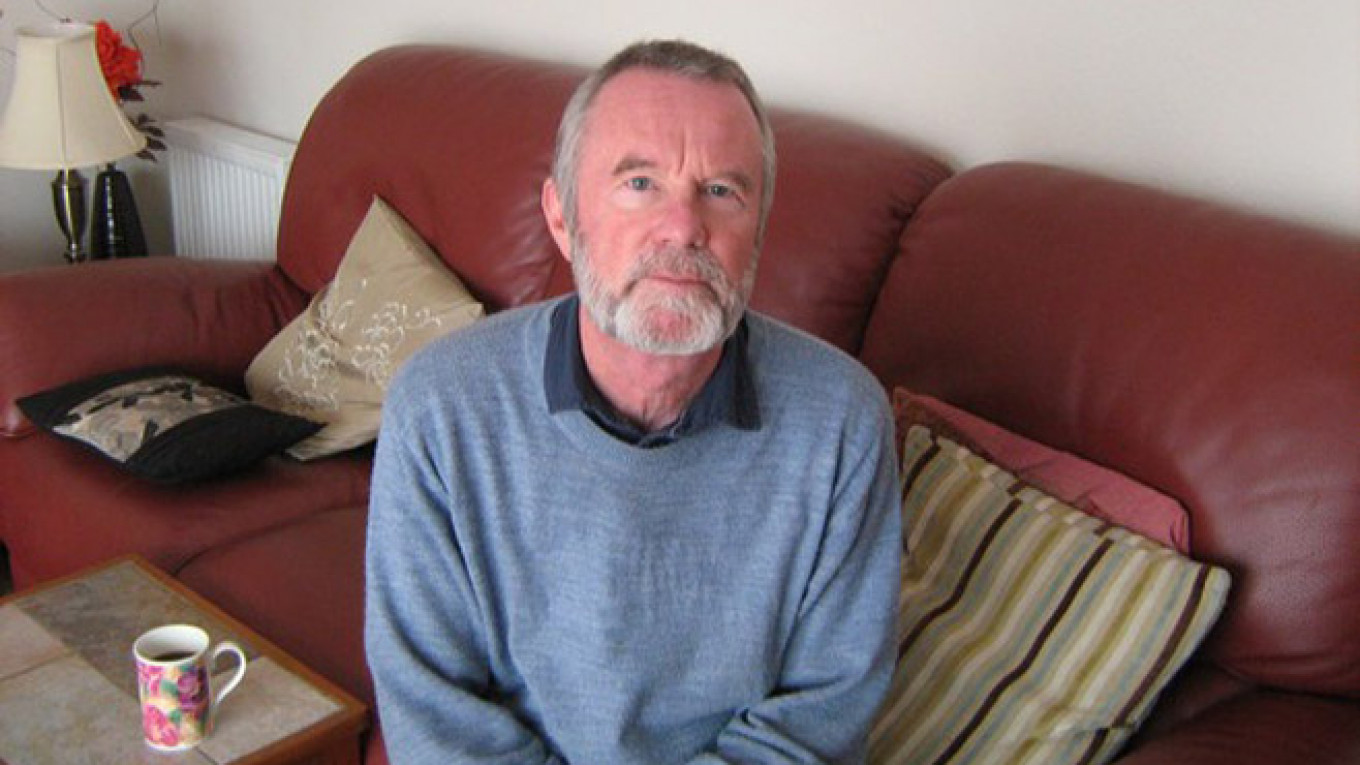

As Russia celebrates the famous poet's 200th birthday, one of his Scottish relatives reflects on his legacy.

In the year 1610, George Learmont, a Scottish army officer and adventurer, quit his native shore and sailed into the wide blue yonder without as much as a forwarding address. Records reveal that Captain Learmont hailed originally from the Kingdom of Fife — one of the locations in Shakespeare's play "Macbeth" — and he makes his first appearance in Russian history in 1613 as one of the soldiers of a Polish garrison captured by Russian troops. There were more than a hundred Scotsmen in the garrison and 60 of them chose to enlist in the Russian service. George Learmont was one of those who threw in his lot with Moscow. The fact that he left a wife and family behind in Scotland does not seem to have daunted the freelance soldier in any way. On the contrary, he quickly set about founding a Russian branch of the Clan Learmont. I can't help wondering what happened to the children the stony-hearted man abandoned when he set off for Russia. Were they taken into care, perhaps, after their mother took to drink, or died, or both? Whatever the equivalent of care was, back then. The poorhouse or workhouse, probably.

Seven steps further along the lineage, we find Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov. Born in Moscow in 1814, he didn't last long but achieved much. He was only 26 when he was killed in a duel in July 1841. It seems that Lermontov knew some English, and in one of his poems he expresses nostalgia for a Scotland he has never seen. And there was a woman, of course. Her name was Varenka Lopukhina, the love of Lermontov's life. A watercolor painting of Varenka painted by Lermontov shows her to have been a dark-skinned slender beauty, of whom he wrote: "Alone I sit at dead of night, a burnt-out candle lends me light. My pen upon a notebook traces the loveliest of girlish faces."

My Russian relative claimed that the big book of life preordained certain people to have amazing things happen to them. And the more I learned about him, the more I believed that this might be true. Mikhail Lermontov was buried several times. He was first interred two days after the duel in which he was killed, in the municipal cemetery. Some time later his coffin was moved to the family estate at Tarkhany. Later still, his ashes were placed in the family vault. He seemed restless even after death.

In many ways, the poet was a contradiction in terms. He was a freedom-loving aristocrat whose mother, Maria Mikhailovna Lermontova, owned rich estates. And yet her son hated the idea of serfdom, which would not have made him popular among his peers in Tarkhany — indeed, he wrote about "the tragic solitude of a freedom-loving man." Elsewhere he declares: "My heart remains desolate, my soul has been warped by the world."

It is strange how relatively unknown Lermontov is to the world at large, given his tremendous influence on Russian literature. Because he was not only a poet, it has been claimed that he led the way in establishing the tradition of psychological writing in his native land.

He became famous overnight with the publication of his novel "A Hero of Our Time," hailed on its first appearance as "a triumph of realism." In it, Lermontov describes his thoughts about the members of an entire generation, claiming to have depicted "their vices in all their abandon." His faith in the resilience of the Russian people was unshakeable, but he believed that a "purifying storm" was needed to change their destiny. Prophetic words indeed.

In his chosen realm of poetry, Lermontov was again a man ahead of the pack. For the first time in Russian verse, an ordinary man, a soldier, is the main hero, as seen in his poem "Borodino." Tolstoy said that Lermontov's poem was "the seed from which 'War and Peace' sprouted." Borodino was a pivotal battle in Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812 and the poem was published on the 25th anniversary of the battle, in Pushkin's literary magazine Sovremennik.

In the village of Lermontovo in present-day Armenia there is a small manor-house museum, on the second floor of which is a desk with Lermontov's inkpot and a rough draft of his drama "Two Brothers." The desk is beside a window from which "the poet of the Caucasus" could look out at the snowbound countryside while smoking the pipe that now lies on his desk.

Imagine my delight when I started to trace my ancestry and discovered my (albeit distant) relationship to the great writer. His paternal family descended from the Scottish Learmonts, more exactly from Yury (George) Learmont, whom I mentioned earlier. Researching even further back, I found that the famous 13th-century Scottish poet "Thomas the Rhymer" could also be claimed as a mutual ancestor. Thomas was a "laird" and "prophet" and was also known as Thomas Learmont. The fact that he was a "rhymer" makes one wonder whether there is a specific gene for poetry that lay dormant for generations until it surfaced again in Mikhail Lermontov. Perhaps I ought to buy myself a quill and some parchment?

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.