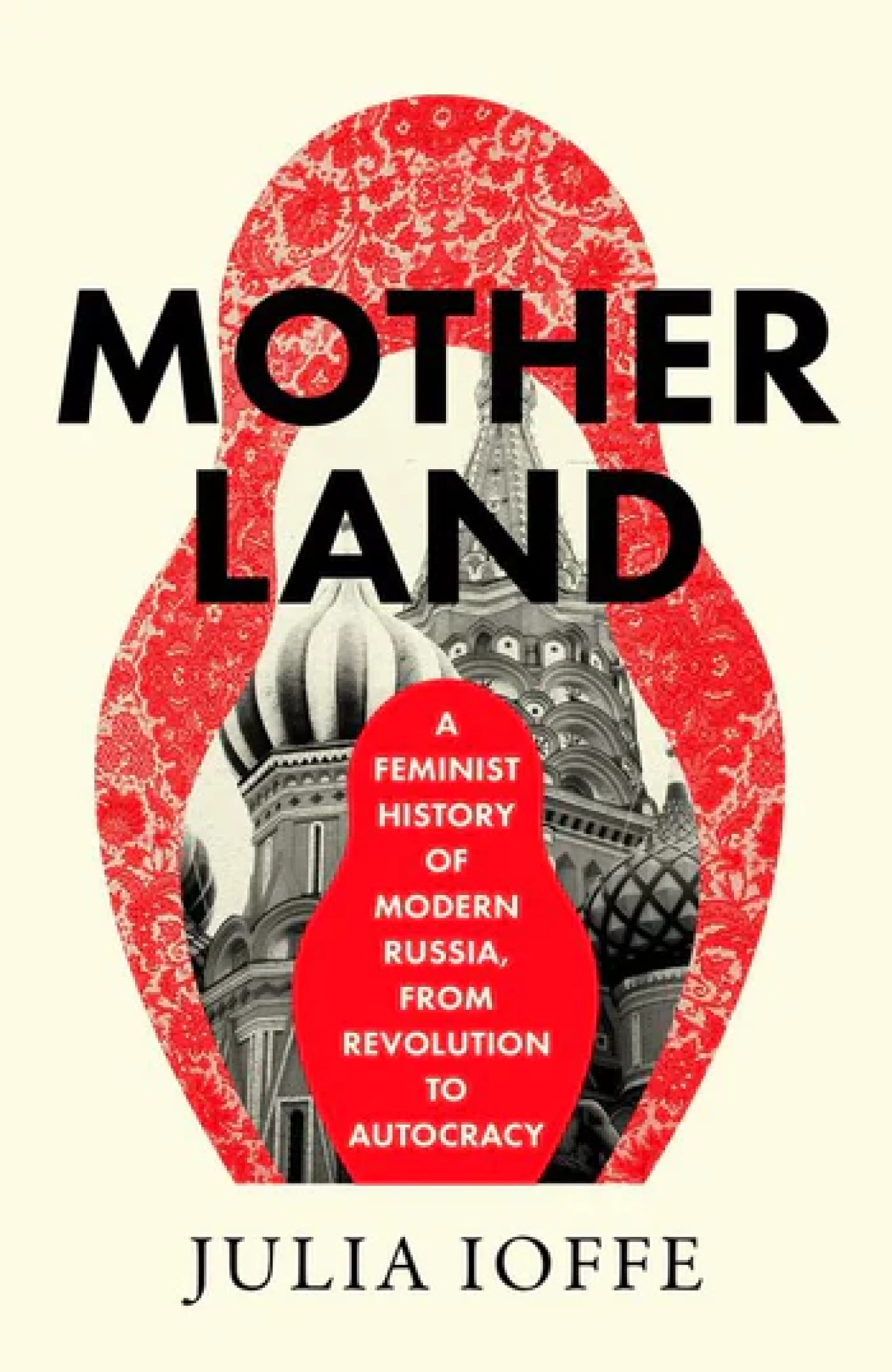

Julia Ioffe is an award-winning Russian-born American journalist and author specializing in Russia-U.S. relations and politics.

Her debut book, “Motherland: A Feminist History of Modern Russia, From Revolution to Autocracy,” tells the story of Russia through its women: from Julia's physician great-grandmothers to feminist revolutionaries, from the single mothers who rebuilt the postwar U.S.S.R. to the members of Pussy Riot.

We spoke with Julia about the experiences of women in the Soviet feminist experiment, the differences between Western and Russian feminism, the lessons we can learn from the women in “Motherland” and more.

PH: Your book is woven around the stories of women over the past 150 years of Russian history, including generations of your own family. Can you introduce us to some of them?

JI: All four of my great-grandmothers were born around 1900, which made them about 17 or 18 when the Revolution happened. They were the first generation to live through the revolution and all its reforms kicked in right as they were reaching adulthood. And they benefited from it tremendously.

They got access to free higher education, which had been closed to them both as women and as Jews, and as some of them being from poor families. This experiment in emancipating women radically transformed their lives. But it did so alongside all of the chaos and bloodletting and tragedy that the rest of the Soviet experiment also brought.

So I start with them, and then I go forward chronologically. The frame for the book came from Nina Khrushcheva, Nikita Khrushchev's great-granddaughter. She said that if you notice the fate of the women at the top, the women who were married to the leaders of the Soviet Union, that reflects the fate of the country more broadly. So I used the women at the top, the first ladies, if you will, to chronicle the fate of the country, and then my family and other women to show what ordinary Soviets lived through.

‘Motherland’ begins with the Bolsheviks, with ideas of egalitarianism and powerful progressive women like Alexandra Kollontai. They fought for truly revolutionary rights, and women did achieve a level of liberation unheard of anywhere else for a while. Could you tell us a bit about these rights?

In 1918, Soviet women were granted the right to paid maternity leave. They were allowed to marry and divorce in a civil court, a no-fault civil divorce. They were entitled to seek child support from the father of the child, even if they were not married, and the father of the child would have to start paying child support even before the child was born.

They were no longer required to change their name or move with their husband and follow them around. They were, in 1920, given the right to abortion, and also the state promised that it would provide free child care, that it would collectivize domestic labor by opening collective laundromats and nurseries and cafeterias so that women could focus their energy on labor outside the home the way men did. A lot of this was just on paper, but it was still more than women in the West had.

In the book you mention a tension or contradiction in Soviet policy over the reasons for women’s emancipation, whether it was for themselves, an innate right to be free, or whether it is for the state. There is the sense that they were only really liberated insofar as it did serve the state. Is that fair to say?

In all fairness, the men existed for the state too. It's a collectivist authoritarian model where the people exist to serve the state rather than vice versa. Would it also be fair to say that the women's experience day-to-day was quite different from these initial ideals? Absolutely.

On one hand, they were able to marry and divorce more freely, they were granted maternity leave, they were allowed into institutions of higher learning where they made up anywhere from, in the sciences for example, a quarter of physics students to 80% of biology students.

On the other hand, the state support didn't often materialize. When it did materialize, it was incredibly subpar because the state had other priorities like fighting wars and fighting its own population through vast political repressions. And because there were so few men after the first half of the 20th century in the Soviet Union, and because the men in charge never abandoned these old patriarchal ideals, nor were they abandoned in the culture at large, women just ended up getting, instead of emancipation, just an extra thing to do — which was work outside the home.

By the end of 80 years of Soviet rule, many women just wanted nothing more to do with the feminist experiment. What happened? Could we say that Soviet ‘feminism’ was a myth?

The culture in the Soviet Union, when it came to gender roles, didn't change enough. The leadership at the top, which was almost exclusively male, did not want to change it because they were quite traditional themselves when it came to gender roles.

And in part, because it wasn't like in the West where women were fighting for it for decades from the ground up. These rights were granted to them. There were a lot of women who also resisted this. When I read in my great-grandmother's letters, the one who was a chemist, that she didn't want all this responsibility, that she just wanted to be a ‘little woman’ in her parlance, it gave me an inkling that not everybody — even the women — wanted this.

In post-Soviet Russia there was a pushback against the have-it-all, career-and-family ideal, and a movement towards traditional gender roles at an individual level. Your chapter about the Life Academy [a program that teaches a philosophy of ‘feminine power’ to help women find economically secure marriages], and its entrepreneurial take on traditional values and lifestyle, made me think of aspirational tradwife content. Can we draw any comparisons between this female enterprise of the early 2000s with the tradwife movement 20 years later?

The similarities are that it's a yearning and an aspiration for something simpler and more ‘natural,’ right? That men are just naturally hunters, and women are naturally keepers of the hearth, and so let's not overburden women with male tasks, it's unnatural to them, and exhausting because it's unnatural. And in this telling, it's why men are lonely, it's why women are lonely.

But I think the divergence is that given the kind of pre-industrial, unmechanized households that Soviet women came from, the tradwife thing — where you make cereal or bread from scratch or you are a homesteader on some farm, and you gather eggs from your chickens every morning — that sounds horrible to a lot of Russian women. That's what they came from — if not in their lifetimes, then certainly in their mothers’ or grandmothers’ lifetimes. I think they want to be a trophy wife, rather than a tradwife.

They want to be the kind of elite luxury wife who spends her time and her husband’s money on beauty procedures, on relaxation, on shopping, on playing with her kids. The kind of wife they want to be still has domestic help and supermarkets, but they just want to relax, to rest. They don't want to do more things, which is what the tradwife is doing.

,In your chapter about Pussy Riot, you highlight the ‘chasm’ between American and Russian feminism. Could you tell us about some of those differences, and what are the problems with applying Western feminism to Russia?

Soviet feminism (though they would have never called it feminism) and American feminism are kind of inversions of each other. Soviet women had the right to work outside the home and higher education. Being a working mother, they'd been doing that for generations by the time second wave feminism came about in the West and Western women started talking about having it all, balancing home and life. As American women were starting to discuss that, Soviet and Russian women wanted to retreat from that, because they were tired.

Also, in terms of reproductive rights, Soviet women and Russian women take abortion and reproductive choice for granted, because they've had it for over a century. Even now, as the Kremlin is curbing abortion access in Russia, it's still afraid to get rid of it because such large majorities of Russian women and men are so against it. So while American and Western women were fighting for this, women in the Soviet Union had had it for generations.

The other thing is that portraying all feminism as Western or American, as something that is imported into Russia, actually helps Putin a lot. If feminism is seen as an invasive species from America that destroys the local values ecosystem, as opposed to an indigenous species that has its own deep roots and history, this helps Putin stamp it out.

Could we say that Putin is afraid of feminists? I understand feminism can be labeled as a nefarious Western import, but it feels deeper than that.

I think it's just part of his general worldview that society has to look a certain way and be a certain way. In this sense he is like Stalin — this is just how things are and how they should be: that men have certain roles, and women have certain roles, and it needs to be this way for families to function, for societies to function and therefore for the Russian government to function.

I don't think that he would see it as taking away women's rights; it would be about restoring a natural order to things. And that it's us who are perverting nature, asking women to be something they're not, asking men to accept women as something they're not and therefore to be themselves something they're not.

If we look at women in Russia since the full-scale invasion, there are movements like Feminist Anti-War Resistance, but one of your chapters addresses a completely different movement of women opposing the mobilization of their men to fight in Ukraine — but very notably, not opposing the war itself. Why have they not had the same impact in comparison to, for example, the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers against the Chechen War?

They're dealing with a fundamentally different Russian state, one that is stronger and much more repressive and committed to stamping out any dissent than in the 1980s or 1990s, during the Soviet-Afghan War and First Chechen War.

This is something that people ask me about all the time, which rubs me the wrong way for the same reasons as when people say: ‘Surely when the body bags start coming home and more and more Russian soldiers are killed, their wives and mothers will protest and end the war and fix it?’ — but they didn't start the war. They have no political power. It was not their decision. Why is it on them to clean up yet another mess that they didn't make?

Most Russians support the war, even if they didn't like that it started now that they're in it. They feel like it would be bad for Russia to lose because nobody wants to lose. Some Russian women actually do support the war, or they don't support the war, but they're too scared because people are being sent to jail, including kids, for such minor things as comments or likes on Facebook.

We're not asking the men to come out and protest in these conditions. We're not asking them to be totally different from the society that they're a product of. We're not asking them to face these superhuman dangers. But for some reason, we expect women to be these superheroes just because they're women. We believe that women are inherently peacemakers, because they're just more gentle and empathetic.

‘Motherland’ is a difficult read. There are many harrowing episodes, including some very personal to your family, and sometimes it feels hopeless. But regardless, it is a book about strong women. Is there any hope? Can we learn any lessons from the women in your book?

One of my goals with the book was to make people stare into the abyss. To make them confront what history actually looked like for the women and the families who lived this insane century in that part of the world.

The first lesson is that progress is not — for example, when it comes to gender equality or equality of opportunity — progress is not inevitable. It's not irreversible. And it needs to be fought for and protected all the time

The second lesson is the need to reclaim not just our own political power, but to reclaim our narrative and historical power. We’re seeing this backlash against, at least in the U.S., against DEI and wokeism, etc., and that's absolutely the wrong approach to take. There are so many important, dangerous things we leave unsaid because of who gets to write the narrative and the history.

The third lesson is that it's not on women to clean up men's messes. It's not on women to be superhuman saviors for men who somehow get to have it both ways — to have all the power and all the resources, but then pretend that they're super vulnerable and need saving.

This article was originally published by Pushkin House and has been abridged and adapted for The Moscow Times. For more information about the book, see the Pushkin House Bookshop site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.