On April 25, Trinity College, Cambridge University, held a symposium at which the only known recording of Harold 'Kim' Philby addressing the KGB was played for the first time. Recovered from a Moscow intelligence archive, it was recorded in 1977 and is mostly about whether agents should ever confess. However, what Philby never told the Russians is that he himself had partially confessed in a moment described by Times journalist and espionage historian Ben Macintyre as "one of the most important conversations in the history of the Cold War"

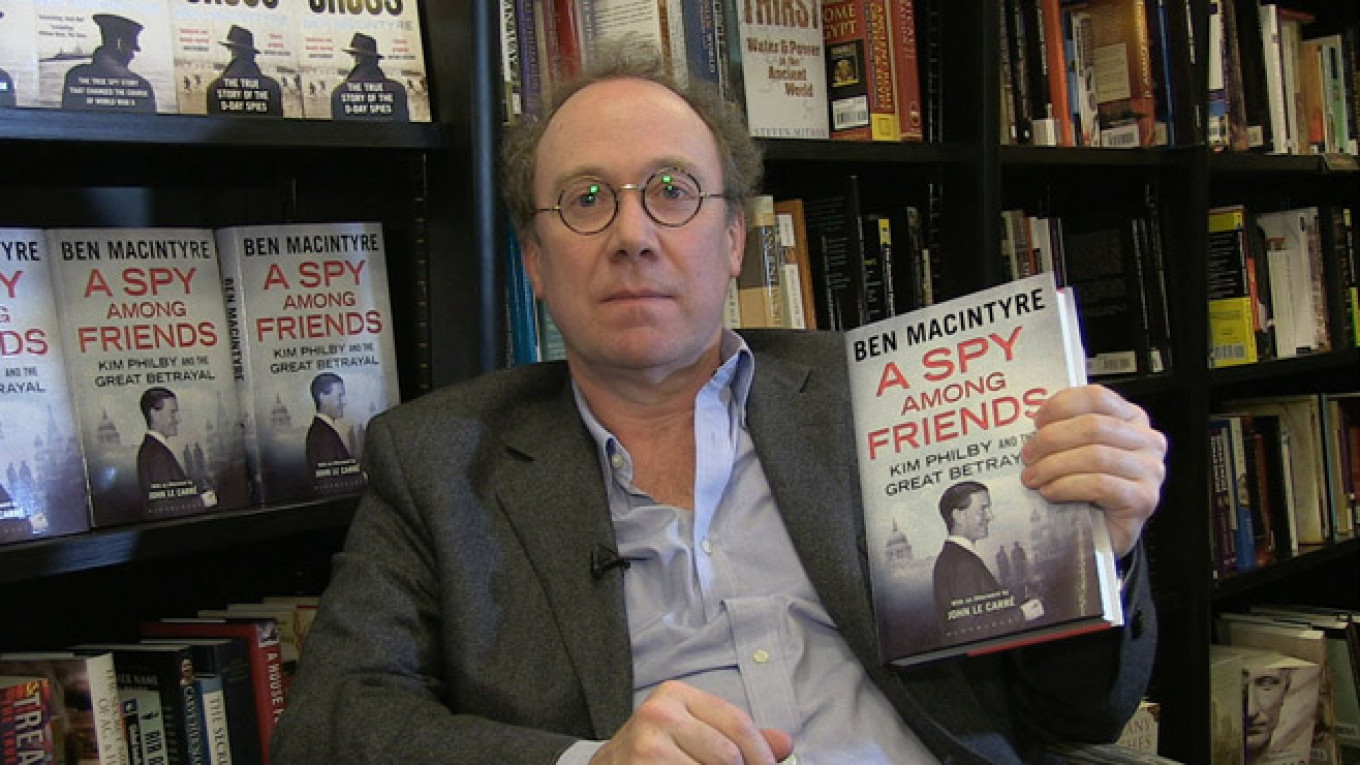

For the British, Kim Philby reiterates the image of a Cold War traitor, and just published in Britain to critical acclaim is Macintyre's "A Spy Amongst Friends," an insightful biography of MI6 agent and Soviet mole who defected to Moscow in 1963. There was also an accompanying BBC documentary by Macintyre, "His Most Intimate Betrayal," broadcast in March.

The author had access to recently released MI5 files and family papers, along with the cooperation of former intelligence officers, though not MI6. "MI6 will never release its files on Kim Philby," Macintyre told The Moscow Times. "One, MI6 doesn't release its files anyway, and two, these particular files are so embarrassing and so damaging to the security service that these are the very last files they would consider releasing."

Unlike the voluminous accounts of Philby already published which have focused on ideology and politics, Mcintyre says that the key to understanding Philby is friendship. "It is often said that there is an acronym which is used to explain the motivation of the spy and that is MICE: Money, Ideology, Coercion and Ego. But actually I think there is a fifth one and that is friendship. And friendship is often the basis of many intelligence relationships."

"A Spy Among Friends"

At the center of the book is Philby's friendship with — and betrayal of — his MI6 colleague Nicholas Elliot. Philby's partial confession came when Elliot confronted Philby in Beirut in January 1963. The reason Macintyre sees this as such a crucial moment is because Philby was the most effective spy of the Cold War. Here was a man who had served as the chief British intelligence officer in Washington between 1949 and 1951. "He managed to get to the top of MI6 while working for the Soviets; no one has ever done that in any other circumstance. So there is no doubt that Philby was responsible for destroying a large part of the West's intelligence operation capability. There are CIA officers who even today say 'We would have been better off doing nothing' as a result of Philby. He absolutely undermined everything."

The other two Cambridge spies, Guy Burgess and Donald MacLean, had long since been unmasked and fled to Moscow in 1951, but Philby remained undetected and was even cleared by the head of MI6, Stewart Menzies. After all, he had come from a good family, been educated at Westminster public school and Cambridge, even belonged to the right club — Whites — so how could he possibly be a traitor? "The clubbiness, the bonding of that particular tribe explains a great deal of how Philby remained effectively invisible," Macintyre said.

And that highly privileged background only adds to the complexity of Philby, a man who devoted his life to communism though "as far as we can work out, never read a word of Marx, let alone ever had any contact with a member of the Proletariat," said Macintyre, referring to the fact that Philby was not interested in the working class. "For a Communist he led a very non-Communist life. I mean, 'champagne socialist' does not even begin to touch it."

Philby always maintained consistent loyalty to the Communist cause and often presented himself as a pure ideologue. But Macintyre does not think this is necessarily true: "For example, I think he was trapped. As I say in the book, the KGB is not a club from which you can resign. And I think he had very little choice but to keep going at the time."

The U.S.S.R. to which Philby defected was not one which welcomed him with any great fanfare. Prior to his defection, Philby was under the belief he had been made a colonel in the KGB. No such thing had happened. The KGB did not trust him: His escape had appeared too easy and therefore that Philby must be playing some triple game. And for the first decade, though treated with respect and given privileges, he "was not allowed into the central citadel of the KGB."

It was not until much later that he was accepted, but given minor jobs. "He was drunk a lot of the time," said Macintyre. "He was very ill. He tried to kill himself at one point, a fact that has never really been brought out before. Philby was actually a wreck, to be honest."

There is an element of the "he would say that, wouldn't he," about Philby describing his life in Moscow as "blissful." In truth, the defector still yearned for British life. He still managed to read The Times, and visitors to his apartment would bring him marmalade and Marmite and back issues of The Spectator magazine. "He was an Englishman in exile, although the exile was — to some extent — voluntary. He could not come back, he was stuck, and he was effectively imprisoned."

For today's generation, the bleakness of the geopolitics from that era is now the stuff of historical biographies, though the current rift in East-West relations has been called a reboot of Cold War hostilities by some commentators. Time magazine recently called Edward Snowden "the renegade in exile," and that could have been an apt description of Philby until his death in Moscow in May 1988 — he is buried in Kuntsevo Cemetery.

Macintyre sees little in common between the CIA drop out and the public school educated high-living Englishman other than their lives as exiles in Russia. "The parallel I suspect is in the lives that Snowden is living now and that Philby lived 50 years ago, because I cannot imagine that Snowden is having a very nice time in Moscow. I suspect he is finding himself in a very, very tricky and cold world out there. In some ways, he is an embarrassment to Russia. He is making life much more difficult for Russian-U.S. relations."

Contact the author at [email protected]

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.