Plump or muscular, feminine or masculine, posh or austere, classically flattering or downright grotesque, the one thing that Russian art exhibits on beauty seem to agree on is that there is no single definition of beauty in the country’s modern-day society.

Exhibitions exploring and, at times, tearing apart perceived ideas of physical beauty are currently tucked away in several Moscow galleries.

Two of note include “Venera Sovietskaya” (Soviet Venus) at the Worker and Collective Farm Woman exhibition center and the recently ended “BOYS” at the ZoomLab Studio on Bakuninskaya Ulitsa. The exhibits explore female and male beauty, respectively.

“Venera Sovietskaya” focuses on the depiction of women in Soviet art, both in sculpture and in painting. One of the more obvious parallels to draw from these “Venuses in shirts,” as they are described by the gallery, is with the American cultural icon “Rosie the Riveter.”

Rosie and her Soviet counterparts were similarly encouraged to assume some of the more traditionally masculine roles. However, one of the more notable differences between the American wartime worker and her Russian sisters is how little of the feminine sexuality the Soviet women have retained. While Rosie kept on her makeup and even had a cheeky glint, the Soviet female icon almost disappeared into her boiler suit.

Some art experts have also attempted to draw shape-based parallels between the Soviet women and their pre-revolutionary predecessors, such as Boris Kustodiyev’s bright portraits of “Kupchikha”(The Merchant’s Wife) and “Krasavitsa” (Beauty). Academics have even said in the past that Russia has a national penchant for larger bodies, which has endured despite the country’s gradual exposure to the Western ideas of ideal body shape.

However, the post-revolutionary woman assumed her shape through inherent strength and hard manual labor. Defined muscle tone was clearly discernible. Conversely, the women in Kustodiyev’s portraits are sedentary, surrounded by fruit and fine foods, and taking on the cushiony appearance of the mattresses upon which they are reclining or the roundness of the grapes they are eating. Wealth and luxury were clearly assets to the beauty of the pre-revolutionary woman, whereas for the post-revolutionary woman they were shunned.

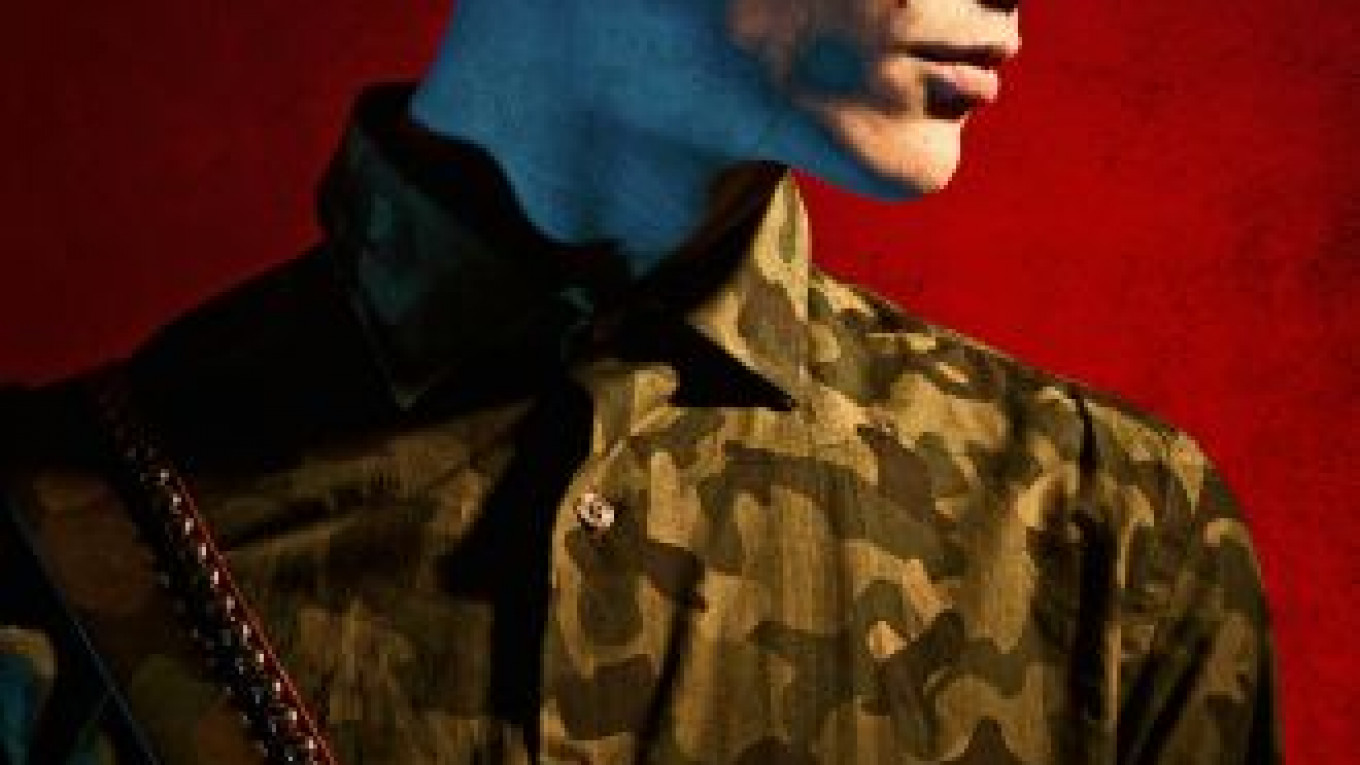

The concept of male beauty in Russia is also changing, as shown by Sasha Guseynova’s “BOYS” exhibit, which strays heavily from the traditional understanding of male beauty. It is possible that the absorption of ideas from the West can be held at least partially responsible for this.

Guseynova, who has so far forged her path through photographing mainly women, captured many of her “BOYS” on film in a more typically female fashion, too. She said that the perceived beauty in modern art and fashion is in conflict with popular Russian ideals of male beauty.

“National consciousness is something that was formed over decades. It says that a man must be brutal,” Guseynova said. “Now fashion dictates completely different things, and our grandparents wonder why boys are like girls, who wear things such as pink socks and colorful trousers. That’s a conflict of fashion and the people’s consciousness. Just try to convince them that it is OK and that you’re not gay. It’s crazy for them.”

Guseynova’s pictures keep an element of the traditional male brutality, but with a twist. Guns and bullets are used by models whose capacity to inflict actual damage seems questionable, and the adoption of such accessories by introspective youths seems tinged with irony.

Some of Guseynova’s models in the more dreamy portraits are very willowy, but most retain their more classical male features, such as a strong jaw, sharp cheekbones and a muscular body. However, the homoeroticism inherent in some is also undeniable, with one shirtless male holding a gun against the forehead of his mirror image in intense rainbow lighting.

When questioned about how long men with more effeminate features have been prominent in Russian culture, Guseynova said that from time immemorial men have dressed as women, such as in the theater, yet this history does not make the modern-day femininity of men any more acceptable to Russian traditionalists.

“Fashion changes and because of this, the idea of beauty turns on its head every season,” she said. “The distortion is not always successful. People in Russia will not be welcoming painted guys in heels for a long time.”

The exhibition "Venera Sovietskaya" runs until Feb. 3 at the Worker and Collective Farm exhibition center, located at 123 Prospekt Mira, Bldg. B. Metro VDNKh; +7-495-683-5640;

Contact the author at [email protected]Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.