At least 1,500 people are imprisoned in Russia for political reasons. Disconnected with the outside world, many of them turn to art as a form of self-expression and therapy.

Perviy Otdel, an organization of lawyers and journalists that defends civil liberties and advocates for the wrongly accused in Russia, has teamed up with the Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights organization Memorial to collect these artworks and show them to the world.

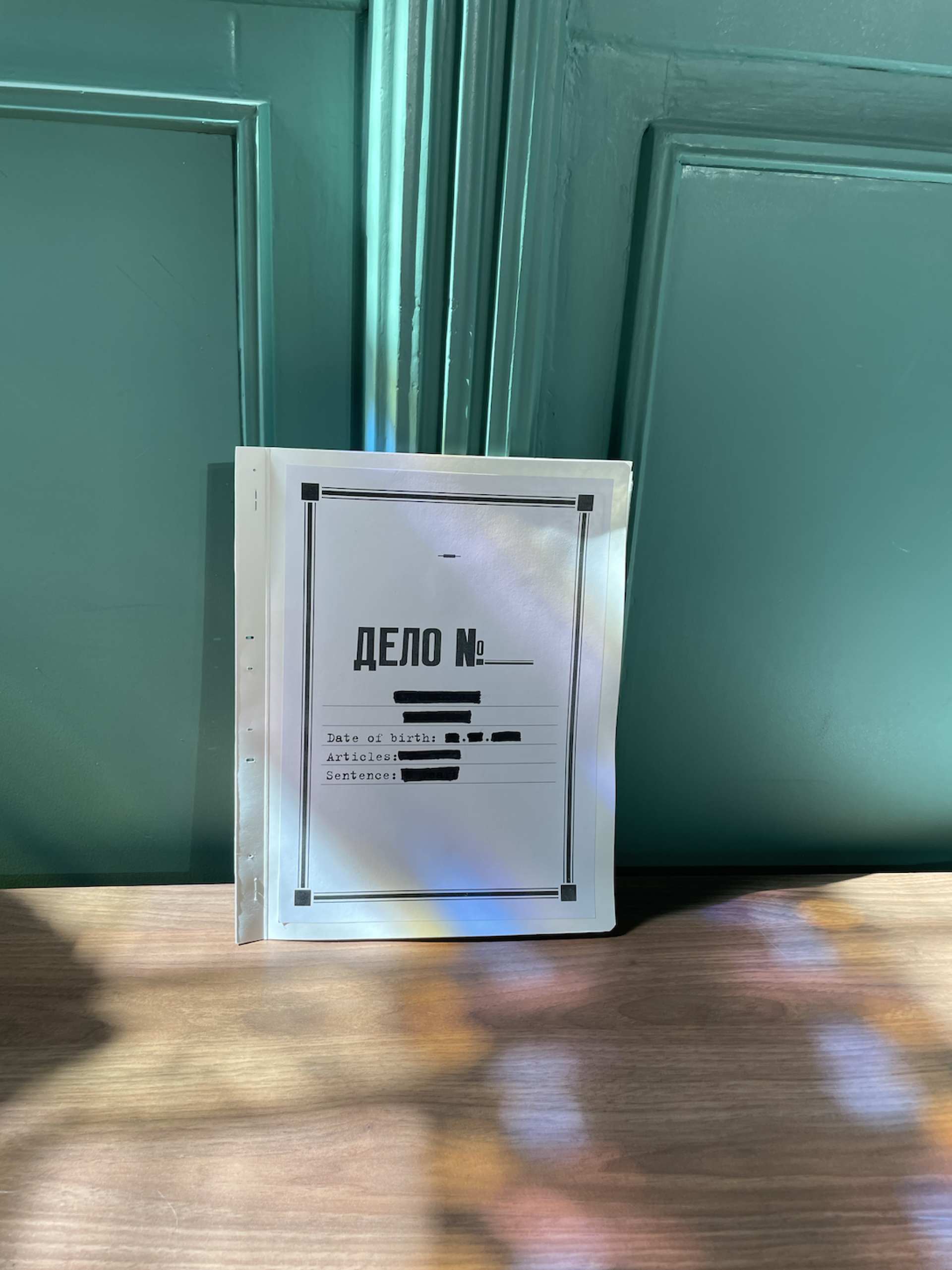

These pieces comprise the Prisoners of Conscience installation at Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition co-organized by The Moscow Times in Amsterdam.

The Moscow Times spoke with Yelena Skvortsova of Perviy Otdel about the installation and their work in exile:

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Moscow Times: Could you tell us a little bit about the exhibition? What do you want people to take away from it?

Yelena Skvortsova: We simply provided the works of political prisoners who agreed to participate in the exhibition. All of them are now in penal colonies or in pre-trial detention centers in Russia, so the drawings were made behind bars and sent to the outside world.

When a person is imprisoned, their life comes to a standstill. Every day is the same, and the most a prisoner can hope for is to receive their sentence and be sent to a penal colony, where they will start working in a sewing factory. But it is hard labor, often 12 hours a day. Self-fulfillment, hobbies or anything else like that are out of the question.

Exhibitions help political prisoners in a psychological sense. One man managed to get everything he needed to paint, created some works, some of which were smuggled out and sent to me, and I passed them on to the exhibition organizers. Thousands of people will see these drawings, and perhaps some of them will write to the artist, share their impressions or offer support.

This won’t set the person free; he’ll still be in prison and will remain there for the next few years or decades. But life goes on — his drawings are being exhibited abroad, and he can interact with the world in this way. Some prisoners have children. For example, Polina Yevtushenko, who is facing 22.5 years in prison for talking about mobilization and posting anti-war messages on Instagram, has a six-year-old daughter who is still free. I think when she gets older, she will enjoy looking back at the photos and publications about her mother and her drawings.

MT: How did the cooperation with Memorial come about?

YS: We created this exhibition together with Memorial. Getting drawings out of prison is not an easy process, so we thought it was right to combine our two collections of drawings.

Initially, we started collecting the works of political prisoners separately from each other and weren’t aware that the other was also doing it.

MT: Artists Against The Kremlin explores how the Kremlin’s practices are infecting other countries, similar to a virus. Does this message resonate with you, or how do you understand your place in the exhibition?

YS: Yes, it resonates. Unfortunately, I can’t influence this in any way, but I can show that ordinary people always suffer from the ambitions of dictators.

Most of the artists whose drawings we submitted to the exhibition have never been involved in politics, journalism or activism. They are ordinary people. Yevtushenko, for example, was detained while leaving a kindergarten where she had taken her daughter. It is very easy to personally relate to stories like this.

MT: How has the role of organizations like Perviy Otdel and Memorial changed now that many of you have to operate in exile?

YS: It's hard for me to say how the other projects have changed, but Perviy Otdel was launched in exile. The people who created the project in 2021 were forced to leave due to repression in the summer of 2021. The main problem that has emerged over the past couple of years is the risk of persecution of people who cooperate with us from Russia. These are lawyers, attorneys and volunteers. Perviy Otdel is recognized as a ‘foreign agent’ in Russia, and repression is constantly intensifying. We have to play it safe and think 10 times about whether we really need to publish information about one of our clients’ cases.

In recent years, 99% of our work has gone ‘underground’ in the sense that we cannot talk about most of the criminal cases we are working on. We cannot call a lawyer or attorney for comment for publication. We are forced to check every comma for security reasons.

Furthermore, I can no longer correspond with political prisoners under my real name, as the censors of some institutions simply do not forward my letters, and investigators, upon learning of our correspondence, begin to blackmail the prisoner and his lawyer.

Of course, blanket blocks also affect our work. Calls on Telegram and WhatsApp are currently blocked in Russia. We expect that no foreign messaging services will still be operational within the next year, which means we will lose contact with our subscribers. Not everyone can afford to pay for a VPN to read our posts on Telegram or Instagram, or to contact a lawyer for consultation, even if the lawyer is located within Russia. It is unsafe to use the state-run messenger [Max], which literally requires a passport to access, or a regular phone.

Prisoners of Conscience is on display at the second edition of Artists Against the Kremlin, an art exhibition organized by The Moscow Times and All Rights Reversed gallery at De Balie in Amsterdam from Aug. 15-Sept. 4.

Visit the exhibition website for more information.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.