A number of analysts have recently attempted to explain why Russian society is so indifferent to the ongoing war, including the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ incursion into the Kursk region. Russians are also indifferent to the recent elections, which ended without a single surprise, and to corruption, which has reached a completely unprecedented scale.

Researchers attribute this to a societal tendency: “In response to radical and significant external changes, which to us as observers seem colossal, Russian society tends to minimize changes in its way of life, thinking and emotions.”

This may be true, but it is not quite clear to me why we are discussing “Russian society” in the first place. It seems that this society does not even exist in a meaningful sense — there is only a collection of individuals who are profoundly alienated from one another.

But in this case, the source of indifference becomes clearer — and much more rational and thorough.

In a relatively normal (I don't like this word, but I won't try to find another one right now) society, a person devotes the most attention to what directly affects their lives, and much less to what has a limited impact. This gives rise to a situation in which people are primarily concerned with their families, jobs, income, material living conditions and social security prospects.

They tend to focus less on issues that affect their communities like infrastructure, state development, preservation of historical heritage or environmental concerns. Issues like foreign policy, defense doctrine and the global balance of power occupy even less of their attention.

This distribution of attention sustains a fairly stable social system, creating a cohesive society built on the interaction of individual interests.

In the Russian context, this dynamic looks different.

Atomized individuals are almost exclusively concerned with their personal interests. They strive to preserve what they've achieved — which is why most people do not even consider attempting to protest, which would bring them significant problems — and, on the other hand, to improve their living conditions.

In this system, the war and the increasing authoritarianism of the regime barely register. While these events make life harder for hundreds of thousands of people — perhaps even millions, when factoring in psychological strain — a much larger number sees them as an opportunity for additional income, government benefits or new job prospects. The extreme rationality of Russians’ individual behavior ensures that the state remains unthreatened by potential dissent.

This atomization also leads to a neglect of the public sphere. For many people, owning an apartment is more important than enjoying a well-maintained urban environment. Having a private car is more valued than good public roads, and access to private healthcare is prioritized over functional public clinics. This allows the authorities to embezzle as much as they want and throw trillions of rubles away on a senseless war without public outcry. In an atomized society, spending on communal welfare feels irrelevant.

At the same time, this disunity fuels a compensatory desire for an abstract unity, provided by the state, which proclaims grandiose but largely unattainable goals that attract little scrutiny.

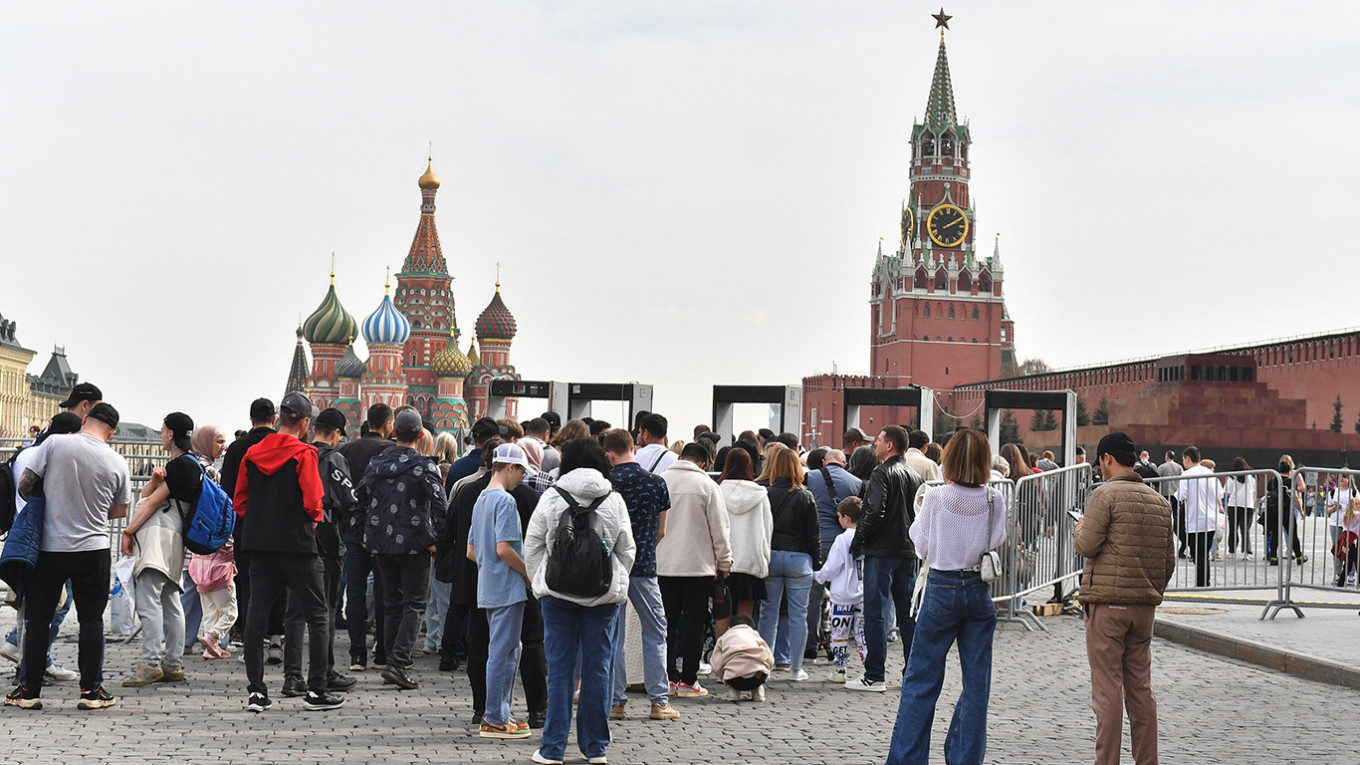

In a normal society, one could illustrate a person’s concerns as concentric circles, with the individual at the center and wider social and political issues radiating outward. But in Russia, this structure has been reduced to two “shining peaks” — individual self-interest and the Kremlin — with a vast desert of indifference in between.

In such a scenario, governance relies on two levers: improving people’s quality of life and feeding them demagoguery about national greatness. In the 2000s, Vladimir Putin emphasized the former. After 2014, he leaned heavily on the latter. By 2022, he had crafted a near-perfect blend of the two.

Throughout modern Russian history, people have never been deeply engaged or outraged by what happens in the space between the individual and the state. This explains why, over the past 30 years, Russia has seen a proliferation of consumer-oriented businesses — from trendy cafés to mobile communications and instant banking services — but no modern highway network, no high-speed trains and no improved living environments outside the megacities. (I am not talking about non-corrupt and efficient local and regional authorities).

The passivity of Russian citizens (not “society,” in the absence thereof), then, is not driven by apathy or emotion, but by a pragmatic calculation of interests.

Do people feel the injustice of corruption? Undoubtedly. But does it directly impact their personal interests? More often than not, the answer is no. In Russia, fighting corruption offers no tangible benefit to individual prosperity. Even if officials steal less, the money saved would likely go toward more bombs and missiles aimed at Ukraine, not toward better hospitals in remote regions.

Do people view the war as criminal and immoral? It’s not out of the question. Yet apart from the brief period of mobilization in the fall of 2022, the war has left most citizens unscathed. Any future consequences — such as reparations to Ukraine in the event of defeat, or the need to reconstruct occupied Ukrainian territories instead of roads and hospitals in Russia in the event of victory — seem distant and unthreatening. Few believe these outcomes would affect their pensions or salaries.

All of this explains the Russian opposition's complete inability to engage the public. Their slogans tend to focus either on moral issues — such as the immorality of war and the need for justice — or on institutional reforms like fighting corruption, democracy and government accountability. Meanwhile, the Kremlin is focused on what resonates with atomized individuals: handing out money and touting unattainable geopolitical ambitions.

Only two things could wake people from their apathy: either widespread poverty or the catastrophic collapse of these grand geopolitical dreams. So far, we have seen neither — let alone both at the same time. As a result, Putin’s stability seems poised to endure for decades to come.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.