Belarus has arrested 33 Russian mercenaries allegedly plotting to destabilize the country ahead of next month's presidential election.

Belarus' KGB security service said the detained men were members of the Wagner group, a shadowy private military firm reportedly controlled by an ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin which promotes Moscow's interests in Ukraine, Syria, Libya and a number of other countries.

The shock announcement is just the latest twist in an extraordinary election campaign that has seen President Alexander Lukashenko, who has dominated Belarus for nearly three decades, jail his key would-be rivals ahead of the vote.

Here’s all you need to know and wanted to ask about the allegations:

How were the Wagner mercenaries caught?

State news agency Belta said the authorities had received information about the arrival of 200 fighters in Belarus "to destabilize the situation during the election campaign."

The ex-Soviet country's security services on Wednesday arrested a group of 32 Russian fighters as well as one other man in a different location.

On Thursday morning, Belarus security council chief Andrei Ravkov said a criminal probe had been launched and that the men face charges of preparing "terrorist acts." He said "a search is going on" to find the others, complaining that it was "like looking for needles in a haystack."

Did Belarus authorities know about their presence in advance?

Descriptions of the men indicate that they were not trying to keep a low profile. Their behavior was "uncharacteristic for Russian tourists" because they didn't drink and their "uniform military-style clothing" drew attention, Belta said.

Analysts say it would have been virtually impossible for Lukashenko to be unaware of the Wagner mercenaries' presence.

“Lukashenko, of course, was aware of why the Wagner fighters were in Minsk and where they were heading,” military correspondent Semyon Pegov wrote.

Are these people really Russian mercenaries?

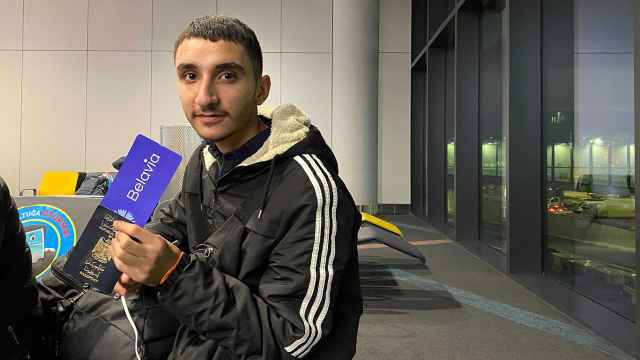

Based on the information that has been revealed, yes. Belta released the names of all 33 men who were detained and Belarussian television aired several of their alleged passport photographs.

“Our own independent research shows that they really are Wagner fighters,” Denis Korotkov, a journalist with the Novaya Gazeta newspaper who specializes in covering the Wagner Group, told The Moscow Times. “We have our own documents identifying a third of the soldiers. Nine names on the list are not known to us yet. Around 10 of them fought in Syria, and around the same number fought in Ukraine. It is harder to provide definite evidence of their involvement in African wars.”

What is Ukraine's role?

Ukraine's relations with Russia have been strained since 2014, when Moscow annexed the Crimean peninsula and conflict broke out between Ukrainian forces and pro-Russian separatists in the country's east.

Ukraine's security service said Thursday it will seek to extradite the detained Russian fighters from Belarus. Authorities in Belarus later asked Kiev to verify whether any of the detained Russians were involved in crimes committed on Ukrainian territory.

How has Russia responded?

The Russian Embassy in Minsk said Wednesday it had been notified of the detention of 32 Russian nationals.

On Thursday, the Kremlin denied trying to "destabilize" Belarus.

Experts have so far pushed forward three main theories as to what happened:

The Wagner soldiers were on their way to a third country from Belarus

During the coronavirus pandemic, Belarus has kept its borders open and operated international flights as usual. Russians have used Belarus as a springboard to travel abroad as their own country has grounded international flights.

This is “the most logical version” of events, Korotkov said. “It is not the usual route used by Wagner, but during the pandemic, it might be useful to use the country as a transit hub for a small number of soldiers.”

The men may have been on their way to Sudan, where the Wagner Group is reportedly active. Video footage showed Sudanese currency among the detained men's belongings.

Military expert Pavel Luzin questioned whether the Wagner Group would use Belarus as a transport hub.

“I don't really see how that would work,” he told the Republic news website. “Wagner is all under the roof of military intelligence. It is convenient for them to work from Russia. There are many quiet places here, many airports, and much easier. I'm not sure that the Russian military intelligence is so at ease in Belarus to start working with mercenaries on the spot there.”

On Thursday, the Russian ambassador to Minsk said the men were in Belarus on their way to a third country and had stayed in a hotel after missing their flight.

The whole thing is orchestrated (with or without Russian approval) to postpone the elections in Belarus

Lukashenko is facing the toughest re-election bid of his 26 years in power in the Aug. 9 vote.

Protests swept the country after his main election rivals were jailed or barred from running. As public discontent builds over his policies and handling of the coronavirus pandemic, protesters have rallied behind the wife of a jailed opposition candidate.

Analysts say the detentions might give Lukashenko the excuse to either further clamp down on the opposition or cancel the election altogether.

At an emergency meeting of all election candidates Thursday morning, Belarus officials said the rest of the 200 Russian militants are still in Belarus and that they are preparing terror attacks, but that the elections aren’t canceled yet.

Belarus investigators on Thursday accused the mercenaries and top Lukashenko critics Sergei Tikhanovsky and Mikola Statkevich of plotting mass unrest ahead of presidential elections. Tikhanovsky, a popular blogger, was jailed last month, preventing him from submitting his own presidential bid. Opposition politician Statkevich was also jailed in the run-up to the election.

Belarussian political scientist Valery Karbalevich told Republic that the Belarussian authorities may have brought in the Wagner fighters to “intimidate the public” and prevent mass protests on election day.

He said two scenarios were most likely: Either the fighters were really flying somewhere in transit, or “Moscow is up to date and even participates in this game.”

“The case will not go to court,” Karbalevich said.

Ultimately, Lukashenko could be painting himself into a difficult corner in which he’ll have to choose between offending Russia or the West, analysts say.

“Releasing the fighters without trial would undermine his claims and be a slap in the face to both Ukraine and the United States, which has sanctioned several Wagner entities for their foreign interference efforts,” wrote Foreign Policy staff writer Amy MacKinnon. “Charging them risks provoking Russia’s ire.”

If Russia was not privy to Belarus' strategy, journalist and political commentator Artyom Shraibman told The Moscow Times he believes the scandal could seriously damage the relationship between Putin and Lukashenko.

Russia wants to integrate Belarus into its territory

In recent years, the two countries have been in talks to integrate closer, even to the point of unifying into a single state. Despite being under increasing pressure to inch closer to Russia, Lukashenko has rejected the idea of outright unification with Moscow.

On Wednesday, political analyst Tatiana Stanovaya cited an unnamed source as saying that Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev has been working with Prigozhin on a project exploring the idea of completely integrating Belarus into Russia’s territory.

It’s unlikely that the Wagner mercenaries were in Belarus to advance this goal, however, Korotkov believed.

“These guys are field soldiers — they can fight but they are not experts of political provocations and they are not specialists in clandestine operations,” he said. “It’s unclear how they can cause instability within Belarus. The Belarussian army would easily overpower them.”

Luzin, however, believes the Wagner mercenaries could be used as “proxies” that can act as civilian protesters, as was the case in eastern Ukraine in 2014.

In general, Russia’s military doesn’t have many ways to intervene in Belarus as it has few bases there, Luzin said.

“Russia is not going to let Belarus go anywhere: If the situation turns into a revolutionary, Moscow will intervene. If Lukashenko wants to transfer power to someone who doesn't suit Moscow, Russia will also intervene,” he told Republic.

Belarussian political expert Yury Tsarik cited anonymous sources as saying that more Russians could been sent to Belarussian cities in order to participate in the protests and further weaken Lukashenko's political position.

"For Russia, this election is a very convenient moment to weaken Lukashenko; he has become uncomfortable for Moscow," he told The Moscow Times. "The unrest could prompt Lukashenko to impose tight measures and push Belarus toward Moscow, isolating it from the international community.”

What does this mean for the two countries' economic ties?

The traditional politico-economic relationship between Moscow and Minsk — a unique setup where Minsk offers “geopolitical loyalty in exchange for privileged economic relations,” as Yauheni Preiherman, director of the Minsk Dialogue Council on International Relations, has said — has already started to fray in recent years.

Lukashenko has increasingly resisted a number of the Kremlin’s latest overtures to strengthen the political alliance through moves such as a single currency or more beefed-up supranational governance bodies, and in return Putin has come good on long-standing threats that Moscow’s cash and cut-price energy is not a gift without strings.

Most recently, Minsk’s ploy to extract maximum financial support without ceding on the political front reached a head in late 2019 and 2020 during customary negotiations over energy prices and transit deals between the two sides and a series of high-profile summits between Lukashenko and Putin. Lukashenko demanded cheaper energy and compensation from Russia for tax changes which damaged Belarus’ finances. Putin — echoing Lukashenko’s position over the geopolitical initiatives — refused to budge.

In a warning which now looks prescient, Artyom Shraibman said at the time: “The two countries are irrevocably set on a path of cooler and more pragmatic relations. This process may result in a situation that is healthier for both sides, but it’s unlikely to be without incident.

AFP contributed reporting to this article.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.