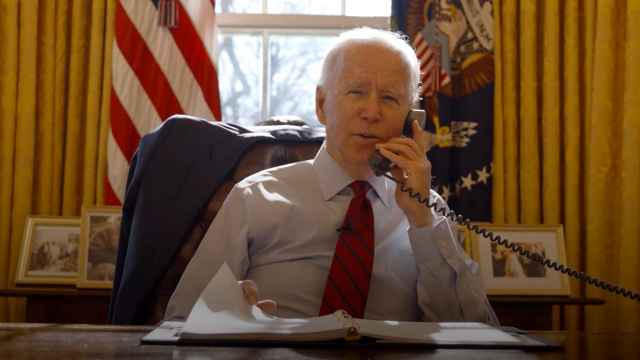

Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin sought to cool tensions in the combustible U.S.-Russian relationship at their first summit in Geneva on Wednesday, but the U.S. president drew a red line at cyberattacks, declaring them "off limits."

The two leaders emerged in mostly positive moods after more than three hours of talks, including two hours alone with just the Russian foreign minister and U.S. secretary of state.

"The conversation was absolutely constructive," Putin told reporters, adding that they had agreed for their ambassadors to resume their posts in a gesture of diplomatic healing.

Biden called the session, conducted at an elegant villa on the shores of Lake Geneva, "good, positive."

The U.S. president, who was ending a grueling diplomatic tour of Europe, said he and Putin explored working together on a half dozen areas where the former superpower rivals have overlapping interests, including the Arctic, Iran and Syria.

Biden told a press conference that the two biggest nuclear powers "share a unique responsibility" on the world stage.

However, despite the mutual warm words, Biden said the meeting was more about having a chance to calmly air disagreements.

Biden said he had "established a clear basis on how we intend to work with Russia."

While both leaders said no "threats" were issued during the talks, Biden was emphatic about warning the Kremlin over any cyberattacks against what he said were 16 clearly defined areas of U.S. critical infrastructure.

Those areas, which he did not make public, "should be off limits." Violations, Biden warned, would lead to a U.S. response in kind — "cyber."

To suggestions that the world could witness a repeat of the 20th century's Cold War — when Washington and Moscow spent decades in a nuclear standoff before the Soviet Union finally collapsed — Biden said Putin knows that modern Russia is too weak.

"I think that the last thing he wants now is a Cold War," Biden said.

Diplomatic breakdown

Diplomatic relations between Moscow and Washington had all but broken down since Biden took office in January.

After Biden likened Putin to a "killer," Russia in March took the rare step of recalling its ambassador Anatoly Antonov. The U.S. envoy, John Sullivan, likewise returned to Washington.

But the summit immediately got off to a good start, with the two leaders shaking hands.

"We are trying to determine where we have a mutual interest, where we can cooperate; and where we don't, establish a predictable and rational way in which we disagree — two great powers," Biden said in opening remarks.

At his press conference after the summit, Putin signaled progress in a number of areas, including an agreement to "start consultations on cybersecurity."

But Putin also issued withering rejections of criticism over his human rights record and allegations of harboring cyber criminals.

He claimed instead that "the largest number of cyberattacks in the world are carried out from the U.S. space."

He also sought to deflect criticism of his treatment of opponents — many high profile opposition figures have been killed in Russia during his rule and the media is almost entirely muzzled — saying that the United States had bigger problems.

Biden called Putin's critique "ridiculous."

Respect

The offer of a more understanding US-Russian relationship — if not necessarily a more friendly one — went a long way toward what Putin is reportedly seeking: increased respect on the world stage.

Biden's reference to the United States and Russia as "two great powers" was sure to please the Kremlin leader, who has dominated his country for two decades, infuriating the West with invasions of Ukraine and Georgia, and often brutal crushing of political dissent.

The choice of Geneva recalled the Cold War summit between U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the Swiss city in 1985.

The summit villa, encircled with barbed wire, was under intense security. Grey patrol boats cruised along the lakefront and heavily-armed, camouflaged troops stood guard at a nearby yacht marina.

But in contrast with 1985, tensions are less about strategic nuclear weapons and competing ideologies than what the Biden administration sees as an increasingly rogue regime.

Putin came to the summit arguing that Moscow is simply challenging U.S. hegemony — part of a bid to promote a so-called "multi-polar" world that has seen Russia draw close with the U.S.'s arguably even more powerful adversary China.

In a pre-summit interview with NBC News, he scoffed at allegations that he had anything to do with cyberattacks or the near-fatal poisoning of one of his last remaining domestic opponents, Alexei Navalny.

For Biden, the summit ended an intensive first foreign trip as president. He arrived in Geneva after summits with NATO and the European Union in Brussels, and a G7 summit in Britain.

Unlike in 2018, when Biden's predecessor Donald Trump met Putin in Helsinki, there was no joint press conference at the end of the summit.

The U.S. side clearly wanted to avoid the optics of having Biden sharing that kind of platform with the Russian president.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.