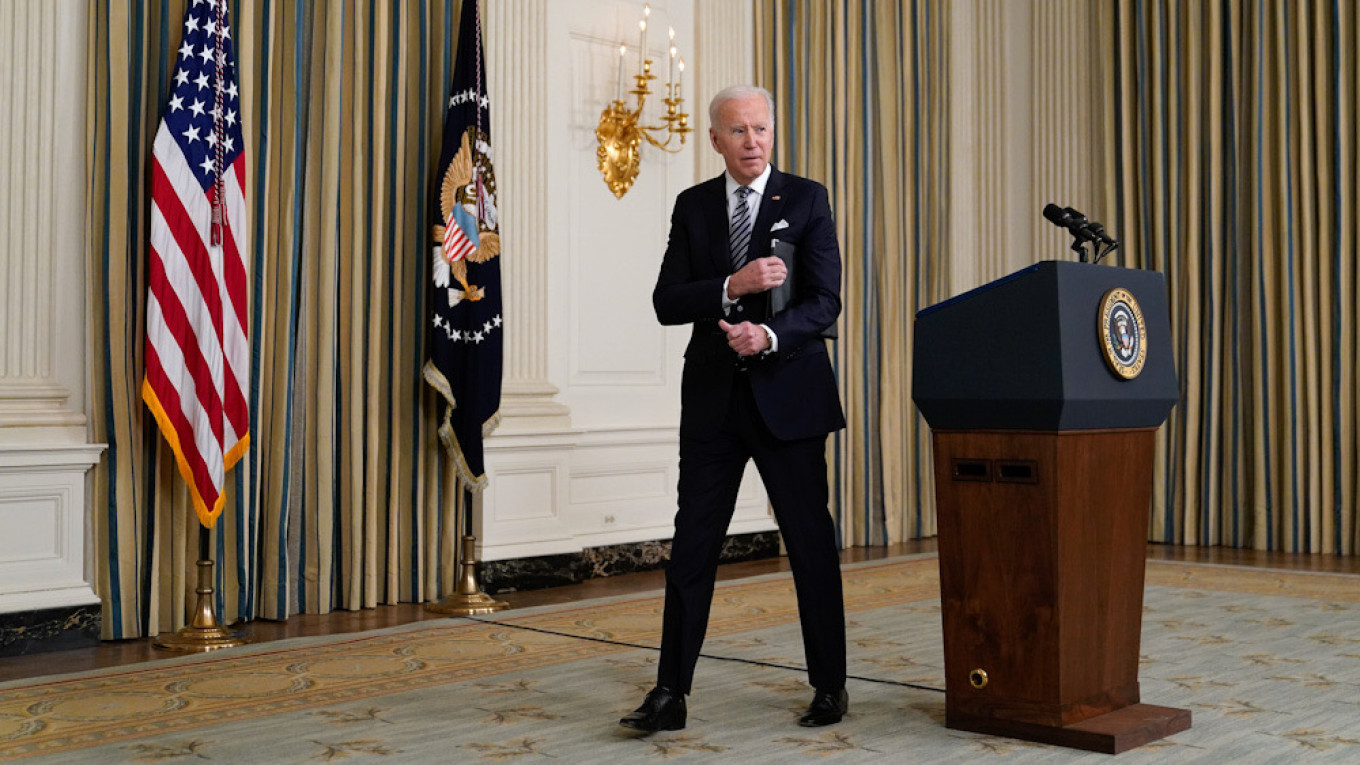

On the eve of the first U.S.-Russia presidential summit between Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden, no one is expecting to see the kind of Gorbachev-Reagan displays of friendship that thawed relations between Moscow and Washington during the Cold War.

In the weeks leading up to the talks in Geneva, Putin has played down the possibility of groundbreaking results, instead painting a picture of a summit aimed at restoring frayed ties between the two countries.

“We will discuss bilateral relations, to try to find a way of regulating tensions,” Putin told the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum on June 4.

According to Russian foreign affairs analysts interviewed by The Moscow Times, the Putin-Biden meeting will focus on restoring some of the basic elements of a diplomatic relationship that has all but collapsed in recent months.

“We shouldn’t expect big breakthroughs,” said Andrei Kortunov, head of the Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC), a Kremlin-aligned think tank.

“The main thing is to stabilize a relationship that has hit a very low level.”

The Geneva summit comes after several months of crisis in Russia’s rarely warm relations with the United States.

In March, the two presidents traded barbs, after Biden agreed with an interviewer’s assessment of Putin as a “killer.”

A series of tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions led to the U.S. embassy in Moscow effectively shutting down, and the two countries’ ambassadors indefinitely recalled for “consultations.”

With the two sides at odds on Russian support for eastern Ukrainian separatists and Belarusian strongman Alexander Lukashenko, Putin told state TV last week that relations had hit “the lowest point in recent years.”

Most observers agree that the Kremlin does not relish the current chaotic relationship with Washington, and will try in Geneva to restore a measure of stability to diplomatic ties.

“The Russian side doesn’t want chaos, they don’t want escalation. They want to reduce risks,” said Kortunov. “I think there’s a hope of re-establishing normal diplomatic relations, with the ambassadors returning to work.”

“But this is where my expectations end. There are still huge areas of dispute.”

Few expect either major breakthroughs or friendly displays from two sides who have grown to take mutual distrust for granted, expecting at most a return to the predictable antagonism of the Cold War era.

“The Russian side wants to move towards a hostile but respectful relationship,” said Vladimir Frolov, a former senior Russian diplomat and foreign affairs analyst.

“They want things to be as they were under Brezhnev in the 1970s and 1980s. No one called each other names, there were no sanctions on individual politicians and no one tried to topple the Soviet leadership by supporting the opposition.”

That final point is likely to represent an especially sensitive sore point in Geneva, where the fate of jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny casts a shadow over proceedings.

U.S. rhetorical support for Navalny — who was arrested and imprisoned on returning from Germany, where he had been recuperating from a poisoning attempt allegedly orchestrated by Russian security services — has been partly responsible for the historic low in U.S.-Russia ties.

At a Friday press conference, a Biden spokeswoman said the president had “every intention to raise human rights abuses,” in response to a reporter's question about Navalny.

For RIAC’s Kortunov, Biden focusing on Navalny risks a repeat of EU foreign policy chief Josep Borell’s disastrous February visit to Moscow, when the bloc’s envoy was humiliated by a round of diplomatic expulsions announced by Russian authorities mid-press conference.

“When Borell came to Moscow, there was a sense he’d come to lecture Russia about Navalny. That triggered an emotional reaction on the Russian side.”

Even so, there is some hope in Russia that Biden may not allow the Navalny issue to compromise broader diplomatic ties, in spite of the U.S. president’s tough rhetoric.

It has not gone unnoticed in Moscow that the sanctions Biden ultimately imposed over Navalny’s poisoning were largely symbolic, targeting only a handful of mid-ranking officials directly implicated in the case, rather than the broader measures demanded by Navalny allies.

“So far, Biden’s policy with sanctions has been very moderate,” said Kortunov.

“He did what he had to do, but nothing more.”

Joint interest

Regardless of the poor state of relations, commentators stress that there are areas of joint interest on which the two presidents might find agreement.

Russia and the U.S. share broadly overlapping agendas on a number of global issues, from opposing North Korean nuclear proliferation to backing a peaceful settlement in Afghanistan.

These shared interests could help smooth the way to a positive outcome for the summit, said former diplomat Frolov.

“It’s possible that they’ll reach agreement over cybersecurity, Afghanistan, or regulating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” he said.

“But this is an optimistic scenario.”

Another potential area of cooperation is the fight against climate change, a political priority for the Biden administration.

With the Russian government increasingly sounding the alarm on rising temperatures’ impact on the country, Putin’s attendance at Biden’s April climate summit was seen as a statement of Russia’s commitment to the issue.

Putin has on several occasions said that he expects to discuss environmental questions with Biden at the Geneva summit.

For some analysts, the real test will come after the summit, as the two sides move cooperation on issues of shared concern forward.

“The summit might only be a starting point,” said Tatyana Stanovaya, founder of R.Politik, a political consultancy firm.

“More important is what happens after — whether Russia and the U.S. are able to set up mechanisms for dialogue to continue working on this positive agenda.”

Personal relationships

Analysts agree that for Putin and Biden — both of whom are political and diplomatic veterans — personal relationships will be crucial in determining both the results of this week’s summit and the future course of diplomatic ties.

Though Biden is a known quantity in the diplomatic arena, with a five-decade record of relatively hawkish positions on Russia, the U.S. president nevertheless remains something of a mystery to the Russian side, according to observers.

In particular, U.S. polarized partisan politics has made the Kremlin — itself burned by the failure of its support for Biden’s predecessor to bear fruit — cautious of any sweeping new deals with Washington.

“Putin doesn’t yet know whether Biden is a strong president who can achieve internal consensus in support of his policies, like Reagan did,” said Kortunov.

“If he turns out to be more like Trump, who was very weak in foreign policy terms, then interest in any agreements will be more limited, because there’s no guarantee that Biden will be able to keep his side of the bargain.”

In any case, analysts caution that the political and personal gulf between the two presidents remains wide, seriously jeopardizing the chance of meaningful results in Geneva.

“Neither Putin nor Biden have much enthusiasm for the diplomatic process, and there’s no love lost between the two,” said Kortunov.

“Then again, in the U.S.-Russian relationship, respect has always been more important than love.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.